|

I

can't remember a time when there was no Mr. Plant. I mean that

he was one of those fixtures of the place that you don't really

focus on-- (like the Spanish tiles that lined the wall opposite

the steam table or the silver tinsel balls that someone had forgotten

to take down from the sconces of several Christmases past)--but

which contributed in their own way to the sense of subterranean

failure which was one of the spiritual smells of the whole place. (like the Spanish tiles that lined the wall opposite

the steam table or the silver tinsel balls that someone had forgotten

to take down from the sconces of several Christmases past)--but

which contributed in their own way to the sense of subterranean

failure which was one of the spiritual smells of the whole place.

Mr. Plant was one of the smells that defined the key distinction

between the two nations of the basement Cafeteria--between those

who used the gym and those who lived in the building which houses

the gym. The two rarely mixed (there were a few residents who would

occasionally be seen in the Steam Room--gym privileges were part

of resident rights--but they never used the real facilities--the

weights, the track, the mats--and those users of the facilities

who did live in the Y were usually young men on the New York rise--farm

boys temporarily waiting tables at O'Neal's who were taking acting

or singing or dance and who couldn't afford anything more expensive

than the Y--but who'd move out in a second given the chance. They

were OK and it was assumed that they shared the same contempt for

the residents that we all did--and that they locked their doors

at night).

The Cafeteria was a good place not only to pick up a cheap meal

(although you got what you paid for in grease and yesterday's lettuce)

but to pick up one of the cuties from the gym who might trickle

down for a yogurt after a good afternoon of sweat. It was part

of gym etiquette that making new contacts in the gym itself was

frowned upon--weights were serious business--and although every

one of the gym regulars was aware of the new boy in town (and would

make appropriate sizings-up to friends and fuck-buddies), the gym

floor was like a dance floor between sets--lots of milling around

and posturings but little action. It's a sad comment that with

the appearance of hair dryers in the drying-off areas a lot of

the machismo veneer was also blown off--it was not uncommon in

the now general decadence of the place to occasionally stumble

upon two guys groping each other in the back shower room. But so

much for the Golden Age.

If the gym floor was the dancer without the dance, the basement

cafeteria had at its best the atmosphere of a balcony--a place

where you could sit one out or a place where new contacts could

be made. This usually took the form of sitting next to someone

that you were interested in--not at the same table but close enough--looking

in each other's direction--smiling seldom, an occasional hand dropped

discreetly onto one's jeans or gym trunks--and then a rustling

period of moving around plates or unzipping canvas or leather shoulder

bags to put back or take out something intrinsically unnecessary--a

book, the Times , a green-visored eye shade, a pair of sun-glasses--anything

to indicate that you were leaving. If the other person made the

same rustlings then it was clear sailing. Sufficient time for the

other to complete the embarking rituals and then a nonchalant sail

to the double doors with a confirmatory last look (usually the

first direct look--eye to eye--of the sequence) to establish that

this packing up wasn't mere coincidence, and then a hard tack to

the starboard side which took you around the corner by the basement

elevators and then into the Mens' Room at the end of the Hall.

The Mens' Room (all historical landmarks are capitalized) of the

West Side Y (another national treasure--one of the stately homes

of New York) was where the actual dancing took place. At one time

in its heyday in the late 30's and 40's, the Men's Room at the

Y (a mecca for gays around the world) boasted 12 stalls all looking

on to 12 urinals--enough for one-score-and-four interested in playing

out male rites. The stall doors had broken locks so that they would

swing open accidentally at the flick of a wrist, holes drilled

between stall walls for show and touch, enough space between the

bottom of the stall wall so that two guys on their knees could

literally do anything they wanted to within the privacy and comfort

of their own confessionals. The place was always packed and the

management seemed to affect a laissez-faire attitude--one of the

indigenous components of running a transient hotel for men. But

in recent years the stalls had dwindled from twelve to six to four

and finally to two--the floor being often flooded with water, the

bowls overloaded with the excrement of old men. A guard had also

been installed and the House Manager (Leo was convinced he had

seen him in a managerial position in Buchenwald) seemed to get

off on his sneak attacks and raids. Nonetheless, that little room

was still the locus of tangential lines--all roads still led to

this display case of bulges, biceps, and Roman noses. And this

was where we--the gym regulars--hoped we'd get the opportunity

to make it with the new boys. Make it on the spot--or even better,

now with the stall shortage, exchange pieces of paper (in every

gym bag, nestling among the jock straps and after-glow, were stubs

of pencil and shards of paper just for this purpose) with phone

numbers and locations--those locations closest to Broadway and

64th receiving priority.

There were always new boys and they each received names and epithets

from the regulars. The names usually had something to do with nationality

and/or desirability. For example, Leo's name for a slender fifteen-year

old Puerto Rican boy was JuanEat Me; a blonde who was around for

only a week or so (it happened often in the summer months when

tourism infused new blood into old veins) was called Grethel. Giving

feminine names to the boys established our superiority and protected

us defensively against the reality that very few of us ever made

it beyond the eyeball level with any of them--although this was

something we who were over 30 (or 35 if we'd admitted it) never

discussed. Every now and then, though, something would come along

the pike who would seem to turn every head and everyone on and

he would be the reigning beauty of the place. Such a boy was the

boy we called Rocco.

Rocco was the embodiment of every gay's dream--not a Prince Charming

from a fairy tale book--but the desirable fantasy hunk from the

porn novels that most of us kept tucked away somewhere for those

January nights when it was just too slushy to hit the streets--the

fantasy combination of life guard, tennis ace, truck driver, cowboy,

hitch-hiker, mass murderer.

There were better bodies during that October of 1979 but somehow

Rocco moved beyond simply having perfect tits, the whitest teeth,

the roundest ass with Botticellian dimples, dark hair that seemed

both long and short, straight and wavy at the same time--hair blown

languidly about by the overhead fans of the cafeteria ceiling.

Wordsworth says that there are some qualities which should be

left to music--that language cannot express those ineffable moments

when the light of sense goes out. For many of us that Fall, Rocco

seemed a real bulb-buster.

And we all seemed to see different things in him and perhaps that

was the essence of his magnetism. For me, getting over a brief

fling with a corrupt little Frenchie I'd met at a Vigo retrospective

at the Thalia, Rocco seemed pure innocence of the Donatello school,

a David sans androgyny. For Leo, who scoffed at my comparison,

Rocco was a street-wise hustler, one of those neo-realistic urchins

of Italian cinema, a male Silvana Mangano.

Nonetheless, whatever any of us thought, it was noli me tangare

for all of us. Ceratinly aware that all eyes were on him from the

minute he'd come downstairs from his room on the 11th floor (our

spies were everywhere) till the time he'd take his shower after

a tone-up workout (he never sweat no matter how hard his run/he

never grunted no matter how heavy the weight), Rocco moved though

it all as if he weren't there--or as if we were beyond notice.

Then he'd leave the gym, walk down the two flights to the cafeteria,

pick up his tray, arrange a melon and tea (we all started carrying

Earl Grey), pay his 86¢, take a table remote from everyone

else, eat his melon, sip his tea, and take from his bag a yellow-covered

book which Leo found out to be written in Chinese (or Japanese,

such was the extent of our proficiency in Orientalia). Then, after

about twenty minutes or so, Rocco would get up (as would about

five or six of us as well) and slowly walk to the double doors

(no backward glancing) and then, after what seemed a fraction of

indecision, he would make his way to the elevators which would

whisk him up to his 11th floor aerie.

This was the pattern for a few weeks and we were all getting to

accept the hopelessness of consummation with our coy mistress when,

one particularly cold October day, early in the morning--it must

have been Halloween, only that could account for it--imagine our

surprise as Leo and I walked into the cafeteria and found Rocco

sitting at a corner table in hot debate with, of all people, Mr.

Plant.

"Maybe it's his Father," said Leo, rolling out the 'th'

sound in his typically Dutch way.

"Yeah, sure. Father Time," I said, transferring my bag

to Leo. "Strawberry or plain?" These were yogurt flavors,

of course, and it was my turn to buy.

Leo pulled his scarf-knot around to one side of his neck--this

one was as brightly colored as a puffin's bill. "Chocolate

fudge." It was his stock response. "And a cherry."

"Speaking of which," I said. ""Why don't you

try getting a table next to You-know-who?"

"Bad for the heart," said Leo, pulling a black cape

around him. Leo had a habit of wearing the costumes he was working

on--and this month it was Il Trovatore.

I said something else but it didn't matter. Leo wasn't listening.

Picking up a plastic tray, puppy poop brown, I smiled at Jose--no

matter who was working there they were all called Jose--who ladled

out a poached egg (martyred atop a steam of foggy water), a plain

yogurt, two black coffees, and paid the cashier whom I'd made the

mistake of becoming friendly with. This morning it was sciatica

and her daughter's imminent abortion.. "Tough

luck," I said, handing her my last twenty.

Leo had managed to get within spitting distance of the Plant-Rocco

alliance. But of course HE was facing their table and had an enviably

unimpeded view of 'The Boy.'

"Thanks," he said, without looking up, as I dropped

his breakfast on the table.

"Thanks for the view," I said, looking at a broken mullion.

"Mike, don't be petulant," Leo said. "Besides,

you've got better ears."

I craned my head around. Plant and Rocco were still thick as thieves.

"Where's the cherry?" asked Leo, opening his yogurt.

I raised one eyebrow. "In this place?"

Leo dropped a pill into his coffee--it began spinning and fizzing

around the surface like a child's windup boat. "Hear anything?"

"No, Lucretia," I said. Actually I hadn't been paying

much attention. But now that Leo mentioned it, I zeroed in on the

table behind me with my sonar.

"Something with numbers," I said.

"Comparing sizes?" asked Leo.

"No. Double digits."

"That's what I meant."

Leo pulled out a Flair and began doodling. "What do you think

of a nude Trovatore ?" he said. "The whole chorus lined

up at their anvils, schlongs erect."

"Beating their meat?" It seemed like we'd had this conversation

before--or maybe it was with someone else. Leo had never heard

of too much of a good thing.

"I'm just so sick of gypsies," said Leo. "You can't

realize what a bore they are to costume. And every day the Director

is yelling: 'Something different!' And all that dry ice."

I was chasing my egg around the bowl with a surprisingly clean

spoon. Leo put his pen down to watch. "No friction," he

said, as the egg eluded me again.

"Traction," I said.

"Whatever."

Leo seemed content whenever his language approximated English. "How're

the kiddies?" he asked.

My work and his play seemed our two staples of conversation--along

with cock sizes and amours manqués.

"So-so," I said, noncommittally. I didn't feel like

going into the problems of finding a seventeen-year old amateur

who could play Mrs. Gibbs. "Actually, I had a great idea.

How's it sound to break up the Stage Manager part among the townspeople?"

"Been done before," said Leo, immolating a gypsy in

Flair flames.

"Where?" I asked.

"I don't know. And don't press me--I've almost successfully

buried all recollection of that trout."

"Tripe?"

"Why you persist in doing Wilder..." he trailed off. "When

there's so much good stuff around."

"Like what?" We'd had this conversation before also.

"Like Shakespeare. Titus Andronicus."

"No women."

"A blessing, wouldn't you say?"

"What else?" I asked.

"THE WOMEN."

"No men."

"They're ALL men. Didn't you see the film?" Leo crumpled

up his napkin. "What're they talking about now? And you're

blocking my view."

"Sorry, Juliana."

Leo almost crossed himself. "No profanity," he said.

Then--"Oh God, speaking of old queens, here comes Danny." Danny

was someone that we'd both had--although we were reluctant to admit

it. "If I happen to remember a previous engagement, don't

contradict me."

Danny made tapes for 'talking books' for the blind and had a voice

like the Titanic farting. "Mind if I sit down?" he asked.

Why couldn't one say a simple 'yes.'

"Just leaving," I said.

Leo looked furious. And then his eyes lit up. He pointed with

his head towards the Plant table.

I turned around just in time to see Rocco, standing gym bag in

toto, lean over the table to plant a large kiss on Mr. P's mouth.

"What IS this place coming to?" asked Danny. "These

senior citizens are the worst."

I was now sort of sorry that I couldn't hang around for the dishing

session; when he wanted to, Danny could be very funny.

I winked at Leo.

"Give 'em my regards," he said, dismissing me.

And then for a few seconds I had the privilege of walking behind

Rocco to the cafeteria door, visions of hot buns before me.

We both got to the door at the same time and for one magical instant

our eyes met as I held the door open for him. Not even a thank-you

as he sailed though.

A backwards glance from me--Leo waving a napkin as if he were

in a coronation parade, Danny gulping chili, and Mr. Plant now

absorbed in a book--his thick lenses reflecting the light like

stained-glass poker chips.

The little shit, I thought--he could at least have the decency

not to look like he'd swallowed a canary.

I stepped though the doorway to resume my bun-following but Rocco

had disappeared--a neat but not impossible trick in that labyrinth

of a basement that would have bewildered even Dedalus himself.

I was late, so it was no john. Instead, I climbed the steps, alone,

resuming my thoughts about New Ways to Play Old Plays--and what

word rhymed with 'heart' besides smart, part, dart, and fart

(I was in the process of writing a Country/Western song called "When

you left me, you took the HE out of my heart "--but had gotten

stuck on the next line). If I had thought of it, which I didn't,

for the rest of that day I would give neither Rocco nor Mr. Plant

a second thought.

The next 23 1/2 hours passed pleasantly enough--the search for

Mrs. Gibbs and Emily Webb continued, there was an unexpected letter

from my father in the mail, there was an expected notice from Macy*s

that they'd tried to deliver my new love-seat but I was out--and

that evening I went to a local repertory production of The Playboy

of the Western World with a largely Hispanic cast performing in

an old store-front. The only bummer was that Michael (that was

another bummer--having a boyfriend with the same first name) couldn't

make it. Some flimsy excuse about adenoids (Michael was a dancer.

Ballet. Don't bother looking for the connection)--so I sat alone,

thinking that I might find a loner who might want to share my $3.00

seats--but no luck. And a nightcap at The Works where the free

porn got me horny and I ended up taking home an ichthyologist from

Nova Scotia with a cock like a cod. And the next morning--I don't

know what happened to Mr. Codpiece--I stumbled all forty-two steps

down 62nd Street--from the door of my brownstone (rented, not owned)

to the awning of the Y.

Leo wasn't in the Steam Room and I hoped that he'd scored--I was

getting tired of his innuendos that we do it again for old times

sake--and the only person around the Cafeteria that I knew was

Jimmy, the retired retarded busboy who was always good for a laugh--and,

of course, Mr. Plant who was sitting in his usual place in the

corner. This morning he had a stack of books and yellowed papers

scattered over two tables that looked as if he'd pushed them together.

No sign of Rocco.

But there was a sign of Danny, the talking book, when I got into

the cafeteria line--so I forewent the pleasure of my morning egg

and sidled myself ("She came at me in sections"--stage

direction for some Fred Astaire routine, describing Cyd Charisse,

I think) to the coffee torturer and paid my 35¢ to Esmeralda

(exact change--a quarter and a dime--laid down on the small scale

used for weighing salads by the ounce) and forewent also her matutinal

complaints and looked around for an inconspicuous place to sit.

What the hell, I thought, it's as good a place as any--and I plunked

myself (and my book bag and my gym bag) down at a table in the

corner next to Mr. Plant.

He barely looked up.

Old fart, I thought--which set me off again on my rhyming obsession.

Heart. Chart. Dart.

Mr. Plant didn't look up or acknowledge my presence in any way

that I could tell (it was hard telling, though, through those cola-bottle

lenses of his--they even seemed to have a slight tint about them,

either through design or degeneration) and I pulled out my copy

of Our Town. It had become instinct to look up whenever a new

face (or ass) entered the cafeteria--so I didn't get much reading

done--but I figured that this bunburying was cathartic and prepared

me for a dayful of Dalton.

Jimmy, the busboy, approached my table with a somewhat coffee-grounded

issue of what looked like the NY Times Magazine Section. "Any

luck?" I asked him.

He looked down at me from the height of his short bleached-cotton

smock and organ-grinder-monkey matching cap. "Well that would

depend on what ye be referrin' to."

It was Cockney or Blimey day. Jimmy fancies himself a mimic. Too

bad that Ed Sullivan had passed on.

"Heart," I said.

Stimulus-response. Pavlovian slavering. "How about quart

?" he said.

I could tell he hadn't been thinking about this.

"Doesn't even rhyme," I said.

Jimmy shrugged his shoulders. "Does in County Kent," he

said.

"Well I'm not writing Brigadoon."

"Why not?" he said. "Make it timely. Get Diana

Ross and Sammy Davis, Jr. Call it Niggadoon."

Mr. Plant's paper-fidgeting stopped and I could tell that he was

eavesdropping.

"Or all cookies--dancing cookies." Jimmy looked at me. "Get

it?"

I looked back at him and lit a du Maurier Special Mild.

"Lorna Doone." He was laughing goofily and looking at

Mr. Plant.

"Starring Sara Lee," I said and wished I hadn't. It

wasn't even funny.

"Should ask Mr. Plant," said Jimmy, nodding his head

in my neighbor's direction.

Mr. Plant looked at Jimmy and then at me--and then I returned

the look and then we both bowed our heads to each other. Very Louis

Quinze.

"Here's the Times ," said Jimmy, handing the magazine

to Mr. Plant. "Got a bit grungy--but what do you want for

free? Someone started the puzzle but didn't get too far. In pencil."

Mr. Plant took the paper like it was a dead fish. Should fix him

up with last night's trick, I thought.

"Thanks, James," he said, and I almost spit in my coffee.

The last thing that Jimmy was was a James. Plant went back to his

papers.

"A la carte!" Jimmy almost screamed at me.

As they say in the silents, several heads turned.

"'He took the HE out of heart/And left me a la carte.'"

"That's really stupid," I said.

"So go fuck yourself," said Jimmy. He walked off and

I couldn't tell if he was truly pissed or not. What do I care,

I thought. Jerk. Jerk-off.

Actually, his rhyme didn't sound any stupider than my whole song.

I drained my cup dry and nodded to Danny who was leaving the Cafeteria.

Coast's clear. Time to move out.

But for some reason I didn't. Inertia precox.

I looked towards Mr. Plant, and, after a pause during what I guess

you could call outright staring, he looked up. Our gaze held a

bit and looked like the potential beginning of an eye-wrestling

contest. Jimmy had, after all, in a way, almost introduced us.

A wooden partition, temporary--that had been wedged in a window

frame and had been there at least as long as I'd been going to

the Y and that had been a number of years--blew out into the room.

It had been supposedly keeping the wind out--as well as the light,

warmth, whatever. Jimmy ambled over to retrieve it.

"Windy," I said.

Mr. Plant didn't even reply--could you blame him?--and looked

down at his job of erasing the crossword puzzle. At least I was

spared the embarassment of following up that last line with another

by the simultaneous appearances of Rocco and Leo. At first I thought

they were together but it was only proximity's illusion. Leo gave

me a once-over and a wink. They both double-tracked their separate

ways across the room and Leo asked me if he could get me anything--while

Rocco sat down dourly with Mr. Plant. Or Mr. P--as I thought I'd

call him. Us being such old friends now.

"Cream, Noel?" crooned Leo.

This was also the first time that I'd ever felt that Leo was an

embarassment.

"The usual," I said, in a plangent baritone.

"Honey, with you the usual's weak tea."

"Funny," I said, as Leo spun on point. He was wearing

someone's old otter and I guess that Trovatore had been replaced

by Boris.

At the Plant table, I kept hearing the name Teddy and then I realized

that Teddy was Rocco--or Rocco was Teddy. And something to do with

a loan not coming through. Or some such. What sounded clear was

that Teddy (the former Ms. Rocco) was putting the bite on Mr. P.

Leo returned. "Geez," he said, "it's hot in here."

I wasn't even going to suggest the obvious.

"How're the armpits?" he asked.

This had started when I told Leo that Julia Gibb's maiden name

was Hersey--and that 'Hirci' meant armpit hair. It's a long story.

In any case, this was Leo's new term for my students.

"OK," I said. I didn't know what was bothering me. Then

I decided to be friendly. "Called you last night but you weren't

in."

"I was in," said Leo. "REALLY in, if you catch

my drift."

Well, that was a relief.

"The old in-and-out?" I asked.

"The one and only."

"Anyone I know?"

"I hope not," said Leo, launching into a story of pursuit

and conquest. Somewhat embellished, no doubt.

I was listening with half-an ear--the other ear-and-a-half at

the Plant table, where voices had dropped barely to a whisper.

"How about you?"

I turned my full attention to Leo.

Then a chair scraped behind me and Leo said--"Get a load

of her."

Rocco had thrown a book down on the table and Mr. Plant, usually

sallow, seemed to be reddening. He said something that sounded

like "I'll call"--as Rocco cougared out of the room.

"Easy come," said Leo, in an unnecessarily loud voice.

"Dirty sheets," I replied, laughing.

The moment I had, I wished I hadn't.

Mr. Plant seemed to be busily gathering up his papers.

"Well?" said Leo.

It took me a moment to realize what he was asking.

"So I just had an extra ticket, that's all."

"I didn't ask that," Leo exasperated.

"Oh yeah," I leaned back, deciding to rise to the occasion

in recounting my fish story. Leo, though, was looking up and staring

at something over my shoulder.

I turned around. It was Mr. Plant.

" Buonaparte ," he said to me--and crossed the room

to where Rocco (the former Ms. Teddy) had vanished.

"What's with her?" asked Leo.

"I don't know--but I think I've made a conquest."

What I really meant to say was "a friend."

***

I think maybe the next day was a Saturday or Sunday (is late October

when the Marathon is run?) and the basement Cafeteria was closed--so

the next time I had a chance to see Mr. Plant was a few days after

his Napoleonic retreat. He was sitting in his usual corner. Alone.

With his books and a paper bag. I wondered what he was working

on. Or what he ate. Or if. He did have unusually long eyeteeth,

now that I think of it. So I went through the Cafeteria line and

entered the dining area and expected him to look up and invite

me over--but he didn't. Then both Leo and Rocco soon showed up--both,

but not together--and I realized, as this became a recurrent routine,

that more and more I was watching the Plant table.

"Better get it out of your mind," Leo said. "You

haven't got a chance."

Yeah, sure," I said. But it wasn't Rocco that I was watching.

And then Rocco, who was always the first to leave, would leave

Mr. P with either a kiss or a huff--and right about when I'd be

getting my gear together (so I knew that he had been watching me

all along), Mr. P would amble over to the water cooler, fill a

plastic cup, pop a pill ("a closet junkie," said Leo)

and, on his way back, would utter one of HIS rhyming words--for

instance, Froissart , ecarte , or Rothbart --(better than Jimmy's

pop-tart , you've got to admit, but probably less saleable) and

return to his table with an especially sardonic (I'm never quite

sure what that means, but I think it fits) smile.

And then I got the idea--'neither a borrower or a lender be' to

quote Ms. Elsinore--of bringing him the Sunday Times on Mondays

so he wouldn't have to scrape off someone's French toast or trick

juice.

And life went on.

Our Town was a success, I might add. Michael got replaced by Rodolphe

(another frog, this time a sock fetishist) and Winter was a cummin'

in with its three-week break where I'd plans to do no more than

work on my play and read Ngaio Marshes (if anyone knows how to

pronounce her name, please call in). And then one morning, as I

entered the cafeteria--it must have been during the winter break

because it was about ten o'clock and I had no classes, Mr. Plant

was actually looking at me--and motioned me over with his head.

I sat down in Rocco's chair--it felt warm--and Mr. P, still looking

up, puffed on an unfiltered cigarette, his teeth yellowed by nicotine

(or sunfower seeds) and asked me--"Which sounds better-- constantly

aspires , or aspires constantly ?"

"In what sense?" I asked.

He was clearly disappointed. Another puff--and I hoped I'd get

another chance.

"Pater," he said.

No reaction.

Then--"Giorgione."

Another no reaction.

He sat back in resignation. "Did you ever hear of Pater?" he

asked.

I was wishing that I hadn't sat down. "You mean like in 'father'?"

"Same spelling." No further help.

"I guess not."

Plant put out his cigarette. His fingernails were dirty but not

bitten. I'm a bit of a hand fetishist, myself.

He condescended to explain. "I'm trying to remember a line

from Pater's essay on Giorgione. It's either: 'All art constantly

aspires towards the condition of music'--or--'All art aspires constantly

towards the condition of music.'"

"What for?" I blurted. That was a bit too blurt. "I

mean, are you writing something?"

Mr. Plant's hands fluttered through his yellow papers--they reminded

me of a Victorian professor of mine named Frederic Faverty who

used to lecture on In Memoriam every spring and weep onto his yellow

notes--it was a schoolwide event. "No, I'm just thinking of

it."

"Why don't you look it up?" I asked.

"Don't you ever do that?" he said.

I felt like we had two conversations going at once. I decided

to keep my mouth shut and looked for Leo out of the corner of an

eye--this dialogue was low even in potential anecdotal material.

"Think," he said. It was not an imperative but merely

a repetition.

"Sure," I said. Don't we all?"

His look seemed to indicate not.

"I have it upstairs," Plant said. "But I guess

I'm just too lazy to go up and get it." He laughed--and there

was an expression on his face that I'd read about but never seen--the

'sad twinkle.' "And it's such a mess. I'm supposed to be moved

into a smaller room by the end of the month and I don't know where

half my things are."

He lowered his voice: "The Management." Real James Bond

stuff. All he needed was Boris Karloff's lisp.

"I thought that since you were interested in language and

music that you might remember the quotation and save an old man

a visit to his Martello."

"How do you know I'm interested in music?" I asked.

The old fox. Me, I mean.

"You have the face," he said. And then, when I didn't

reply

--"Well, aren't you?"

Yeah, I guess so," I said, trying to sound Rocky-tough. "Aren't

we all?" I was a bit too Stallone even for my own taste.

"No, I don't think so. Listening as an Art seems dead, too.

Maybe you can use that in your song." Was he being facetious?

or merely sardonic? (I wished I had looked that up. I also wished

that his breath didn't smell so bad).

"So what do you think of that?" he asked. "The

quote from Pater."

I asked him to repeat it.

He did--in both versions, take your pick--adverb before or after.

"I guess it's all right," I said, as if my grudging

approval was going to matter to anyone.

"Interesting writer," Mr. Plant said. "Pater." He

looked into my eyes. That old black magic, I thought. "I think

you'd like him."

I absolutely hated that when someone said that to me. Let alone

someone who didn't even know me. "Oh yeah?" I said, street-tough. "Why?"

Rocco was just entering the room. My senses weren't totally on

holiday.

"I just think that you're a sensitive person and Pater has

a special aesthetic that I think would appeal to someone like you." Lay

it on, baby. "Let's say, he's one of the family." Here

it comes, I thought.

"What family?"

He smiled inscrutably; Mrs. Mao had nothing on this guy.

Rocco sat down in the other chair; he was eyeing me with proprietory

eyes.

"I was just talking about Pater with," Plant looked

at me, "Mr.---."

"Carciofo," I said. Then to Rocco--"Mike."

Firm handshake. Good old buddy, Mike, that's me.

"Mr. Carciofo is a poet," explained Plant. He hadn't

bothered to introduce Rocco/Teddy to me.

"Actually I'm not," I said. "I'm a school teacher."

Rocco looked like he was waiting for me to leave.

"There doesn't have to be a difference," said Plant.

The old fuck.

"Well in this case, there is," I said defensively. Why

didn't I just get up and leave. Why was I digging myself in deeper?

"Mr. Carciofo is writing a book," said Plant to Teddy/Rocco.

Oh, the surliness of youth, I thought.

"Actually a play," I said. "A musical."

Mr. Plant begged to be excused. "I'll just be gone a minute," he

said.

Rocco said he'd come with.

"Why don't you wait?" Plant said.

I could see Leo entering the cafeteria.

"Give you a chance to get acquainted." And he was gone.

How cozy, I thought. What was that character from Chaucer? The

one who pimps his niece? Memory like a sieve.

Silence.

Finally--"What do YOU do?" I asked.

Rocco looked at me as if I were mad. "Dance," he said,

in a how-could-you-think-anything-but, doesn't-it-show tone.

"Oh yeah?" Two could play at this game. "Where?"

"I'm still studying." A classic answer for 'out-of-work.'

He certainly was cute, though, with lashes to die from.

"Who do you study with?" Stiletto time.

"I take classes around." Rocco was fidgety. "Look," he

said. "Tell Paul I had to split and I'll see him later."

Who was Paul? It must have shown on my face.

Rocco indicated with his head towards Plant's empty seat.

"Sure thing," I said. "Nice to meet you."

No response. Polite little bastard. What he needs is a good fuck,

I thought. It was interesting how his surliness was working on

me.

I sat there alone. Somehow it looked like I'd inherited the table.

Leo was sitting by himself and I was just getting up to join him

when Plant returned.

"It's constantly aspires ," he said.

I was thrilled and relayed Rocco's message.

"I know, I met him outside."

Thanks for nothing.

"What do you think of him?" asked Plant.

I wasn't about to be candid. "Nice," I said.

"Antonella da Messina," he said.

I nodded. Ignorance is bliss.

"Do you know that painting in the Kunsthistorisches?" he

said.

"I'm afraid not."

"It looks just like Teddy," said Plant. "A work

of Art. What was it Wilde said? Something about Art imitating Life."

"I think it was the other way around." Two points for

me.

"Oh yes. How well you know your Wilde."

"I've been working on a musical of The Importance of Being

Earnest."

"Another one?" he said.

This time I had the answers. "If you're thinking of Earnest

in Love , it's nothing like that."

"I was thinking of that. How is yours different--or shouldn't

I ask?"

"Ask right ahead," I said. "This one is all stops

out. I mean, contemporary--gay lib, the works."

"Sounds interesting."

Then why didn't he sound interested?

"It is," I said. "I mean it's about time we had

a theatre of our own, isn't it?"

"Our own?"

"I mean a gay theatre."

"I thought theatre was for everyone."

"That's not what I meant. I mean, aren't you sick of going

to the theatre and only seeing straight characters--or an occasional

queer who shoots himself by the Act One curtain?"

"I don't go to the theatre much. I prefer reading plays." So

much for that.

"Too expensive, huh?" A low blow.

"Too vulgar. I'd rather hear it in my head--I suppose that's

what Pater means." He paused. "Or why I like to look

at Teddy. He's perfect; like a portrait."

He's a snot-nosed punk with an over-developed ass, I thought.

"You're a director, you should know these things. 'To burn

always with a hard gem-like flame.'"

I looked up.

"Pater again. This seems to be Pater Day."

"I thought that was in June."

Mr. Plant caught the joke and smiled faintly.

Leo was crossing the room and I got up. I really hadn't intended

leaving the cafeteria but I didn't want to stay. "Nice talking

to you, Paul ," I said.

I motioned to Leo to stop. He came over.

"And nice talking to you, Mr. Carciofo."

Leo was wearing something abducted from the seraglio. He wasn't

shy about waiting for introductions. "Hi," he said. "Leo

van Ritten."

"I'm afraid I've hurt Mr. Carciofo's feelings," Mr.

Plant said to Leo. "I do hope he'll forgive me."

"Forgive you for what?" I feigned.

"I'll try and find that book for you."

Leo looked up and Mr. Plant explained. "Pater."

"Walter Pater--that old queen?" How did Leo know. "Marius

the Pederast?"

Plant actually laughed out loud.

"Let's go," I said.

Plant had pulled out a pencil. "Carciofo," he mused. "That's

a perfect name for you." He looked down.

"Means 'artichoke,' doesn't it?" said Leo.

Mr. Plant smiled. " Constantly aspires ," he said to

me. "Don't forget."

***

The next few days and final week of my Winter vacation passed

pleasantly enough. The foot fetishist got a bit much and I started

doing the round of the bars seriously, cursing the city's slush

and steeling myself to telephone Michael. A bird in the hand, you

know. Combined with a powerful instinct for hibernation. The work

on my play went so-so and "Rearrange My Heart" still

needed a final rhyme, my love-seat was finally delivered, and I'd

had Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow (a not-bad reproduction) framed.

Leo wasn't around much--I assumed he'd gone to New Orleans for

his annual business vacation overseeing Mardi Gras costumes for

one of the float-groups, and Mr. Plant seemed also to have split.

That was just fine with me--it was about time that the drama of

my own life got a new cast of characters. I had a letter from my

Mom and she said she might be coming up from Ecuador. I hadn't

even known she was there. And one nice bonus--since our 'meeting'

that one morning, Rocco was a bit more approachable and we took

turns spotting each other at the heavy weights--he seemed as much

a traditionalist as I am and put as little stock in the Nautilus

as Captain Nemo should have done. It was mostly grunt talk but

it was nice being seen in the company of the reigning beauty--although

it looked like Rocco's season might be fast eclipsed by a Danish

gymnast with Olympic pretensions. What was it Sebastian Venable

said? "Tired of the dark ones; hungry for the light ones." The

days passed and Leo was back one late January day, early a.m.,

and my holiday ended.

"Did you get my card?" was the first thing he said to

me.

The usual 'no'--this imaginary card had been sent to me at least

four years running now and I recalled what a jerk I'd been to even

look for it that first routine.

"Then you don't know my little bit of news," he said,

looking around.

"Guess not," I said, thinking ahead to a one-upper.

"Well, let me tell you honey. I got all the news on Paulette

la Plante."

It took me all of five seconds to focus on who he was talking

about. "Oh?"

"Yes, and it seems that our Mr. Plant was rather well-known

in his time. His time being the 40's."

I looked up. "Well known as what?"

"As a Brechtian," Leo said. He was dressed this morning

like several of the brides for seven brothers.

Our actual dialogue was a series of one-liners from Leo and an

equal number of OH's from me--so I'll simply summarize. Economy

of something. It seems that our Mr. P was a disciple of Bertolt

B in Vienna, of all places--I hadn't known Brecht went there but

I'm not really up on my biographies--and that there had been some

hanky-panky over a play that Plant had written--on forbidden themes--the

kind that dasn't speak its names--and there was also some business

about McCarthy in the 50's and talk of extradition. I think that's

the word--or maybe deportation. End of tale.

"How'd you hear this?" I asked. "Was there a Plant

Festival in New Orleans?"

"No, my dear, straight from the smoking pistil himself. Upstairs,

in the penis gallery."

"How'd that come about."

Leo explained that he'd come to the cafeteria one afternoon and

that there was no one around but Plant and that they got to talking

about Trovatore , of course, and Plant said he knew a lot about

gypsies--in fact, he had some gypsy blood--and some gypsy books

(not written by them but about them)--and that old Stamen Stain

had invited Leo up to rummage. "That was the exact word." Leo

was wiping his lips on a bandana. "Now you know how I love

to rummage, so up I went. And let me tell you--the Collier Brothers

had nothing on him." (The Collier Brothers were a famous pair

of NYC recluses who collected things--this also is a long story

and if you know it, fine. I've always felt that an explained allusion

is about as satisfying as an eaten menu).

"So what happened?"

"What do you mean what happened?"

"Did you do it?"

Leo feigned shock. "Do it. With Prince Gautama? Let me tell

you, Mike, that man is a saint, a downright saint. In fact, it

was perhaps the most positively Platonic apres-midi I've ever spent."

"So what was so special?"

Leo was eyeing a new tray-wielding Teuton who was looking for

a place to sit. "The talk, I guess. The man can actually talk.

I would no more have thought of doing it with Plant than fucking

the Immaculate Conception herself."

"It's not an uncommon fantasy," I said, buttoning my

bookbag.

"Well, anyway, you should go up and see him. Looks a bit

green around the gills."

"All that chlorophyll."

Leo ignored this as if I were blaspheming. "And he told me

special that if I saw you, he had something for you."

"Oh really," I said, secretly pleased, I'll admit. "And

I bet I know what it is."

"You know, Mike," said Leo, examining a tinfoil ashtry

as if it were an Elgin marble, "that's all you have on your

mind. Not everyone walks around cock first."

"It's either that or ass-backwards," I said, annoyed.

"Chacun a son gout ," said Leo, pronouncing the T.

"If he wants me, he knows where to find me."

"Very Lauren Bacall," said Leo--"but you may have

a long wait. From what Jimmy told me, Plant's got a bum ticker--even

the Y is holding up his room change."

"That's news to me," I said, hoping that I sounded seriously

sincere. "Rocco didn't mention anything about it."

"You've been sororitizing with Mlle Rocco?" I loved

the raised eyebrow.

"You could say that," I exaggerated.

"Then he's a little shit," said Leo, rising. "And

maybe you are too."

Leo swept the cigarette butts from the ashtry into my empty egg

saucer and wrapped the ashtray in a paper napkin. "See you," he

said, putting the objet d'art into his

dirndl

blouse.

It was time for me to leave also. "Wait, I'll walk with you."

Leo barely turned around. "I think we're going in different

directions," he said.

"Fuck you," I said silently. What was he so pissed about?

And it was a thought I had for the next few days as Leo made it

a point to sit by himself.

And I began to notice how odd it was that the Plant table was

empty.

***

It was on a Monday afternoon--I had the day off, something about

Founders' Day or some such shit, and my new vehicle (as Blanche

Hudson would have said)--two Stoppards--was between casting and

rehearsal--so I showed up at the Y. It must have been February

because Alpen Strudel (my favorite overpriced Bavarian deli) was

displaying heart-shaped cookies and had finally taken away their

papier mache gingerbread house. There was no one in the gym, at

least that I knew, the basement stalls were an old folk's home,

and the Cafeteria smelled of sewer. So I had a little tea, thought

about where I was going to spend Spring Break, with whom, felt

sorry for myself, decided I needed a little stroking, went home

for my TIMES Magazine section, retraced my forty-two steps--and

picked up the housephone.

No, I didn't know the room number, and yes, he was expecting me.

So I filled out a little card, giving my permanent address as

Fiji and Fifth, and got into the elevator.

I'd been in the elevator before, of course. The Sun Roof (tar,

sticky and hot) was available to members during the summer, and

it was a convenient way of getting into the rest of the Y for a

little floor-to-floor salesmanship. And I knew that the 11th floor

was beaucoup cruisey and had spent many pleasant afternoons in

the suites of johns up there, with an occasional nip and fuck into

someone's room. Typical YMCA room: One bed, single; one dresser,

varnished; one linoleum strip, cracked; one closet, one hanger.

But nothing prepared me for the 12th floor--the elevator itself

stopped at the 11th--and a separate staircase went up to a small

corridor of doors opposite to where you walked up to Tar Beach.

If you could imagine a YMCA with penthouses, this was it. Mr. Plant's

room was 1202 and I knocked. And he opened it.

The Collier Brothers (again that allusion; better look it up)

was not the aptest of comparisons. The Alexandrian Library would

be more like it. Floor to ceiling, wall to wall, double or triple

thickness--books. And not paperbacks but real books, the ones with

Moroccan leather bindings and gold-leafed titles. The room was

also curioulsy lighted--and I realized that it was a combination

of having an unshaded bulb overhead and also covering the only

available window with more books--bricks and boards--with a dingy

sunmote or two trying to get in, or out.

And stifling.

And old man smelly.

The room was larger than the other rooms I'd seen at the Y but

there was the obligatory single bed, dresser, and desk chair (did

I forget to mention that before)--all in the middle of the room.

The bed unmade, of course, the dresser filled with dampish wools

and papers, cigarette butts in coffee saucers, and standing, wearing

a faded maroon smoking jacket over very spindly hairless legs--Ingres

would have killed for a pencil--was Mr. Plant.

He didn't seem surprised to see me, not particularly anyway, and

offered me the chair as I offered him my Sunday Times magazine.

The cover story that week was something about drugs and there was

a photograph of a dripping hypodermic on it. I sat down and put

(almost folded) my hands in my lap and waited to see what would

happen.

Nothing did, other than Mr. Plant sitting down on his bed, crossing

his legs, and offering me one of his unfiltered cigarettes. I took

one and looked around.

"Nice place," I said. Just looking, not buying.

Mr. Plant coughed and lit a cigarette for himself.

I was reminded of the Bianco family who used to live downstairs

from us when I was growing up--old Gramps used to sit on the back

stoop coughing and spitting into a rusty Maxwell House Coffee can

until it was filled up. Then Grandma removed it.

"Lots of books," I added. I knew better than to ask

whether he'd read them all. Someone--I think from CCNY--said I

had the gift of gab. It must have been given away.

I decided to try a third pitch and if it was a strike, I'd simply

leave. "Haven't seen you around much. How've you been?"

A hit! Nothing the elderly like more than the pleasure of recounted

pain.

"I haven't been feeling too well. I think, though, that it's

been mostly psychosomatic. I just can't seem to get these books

ready for moving."

He looked up at me. "The management wants to close off these

rooms--the cleaning staff can't get the vacuums up the steps--and

they want me to move to another room. But, as you know (how would

he know that I knew?) all the other rooms are much smaller and

that means either throwing some of my books out--which pains me

to even contemplate--or giving them awy--or storing them."

"That sounds possible," I said. "Or why don't you

move into some place larger. I mean, outside the Y."

Plant looked towards what should have been the window. "I

guess I'm too old to move, now, and what's the point of having

books if you don't have them around. It would be like getting rid

of a lot of old friends."

He turned to me. "You must know what that's like."

"Sure," I said.

"It's foolish to become so attached to things, but the presence

of these old books kind of fills the room with a soft music." He

laughed quietly. "Do you hear it?

No," I said, "but I know what you mean."

"I thought you would and that's why I asked Leo to tell you

I had something for you." He looked around. "But now

I don't know where I put it. A copy of the Pater, you remember?"

"Oh yeah," I said. "But I can't take one of your

books. Them being old friends and such." Wait till Leo heard

this one. Or wait till I got my hands on Leo.

"You'd be doing me a favor."

I must admit feeling awkward. "What did it look like?"

"Oh, it wasn't much--a Modern Library edition of the Renaissance

Studies. Gray, I think, or that kind of forest green they use."

"Oh yeah," I lied. Talk about needles in haystacks.

Plant looked around without moving from his bed. "I'd offer

you a cup of tea but the hotplate broke."

"That's OK," I said. "I've got to be going anyway.

Heavy date, you know."

"Well, just have one cigarette more." He proffered one.

I took it.

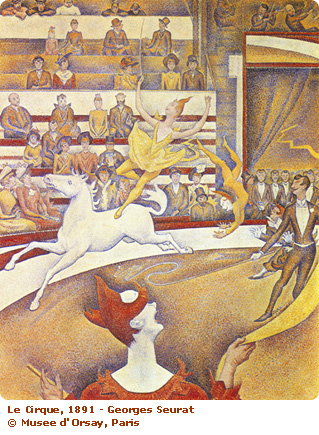

"I somewhat miss the circus," Plant said.

"The circus?" I hadn't know he had been in one.

Plant lit my cigarette with a trembling hand. I had to inhale

fast to get the flame before it blew out.

"That's my word for the Dining Room."

I didn't seem to register comprehension.

"The cafeteria downstairs."

"Oh." I brought up a hearty laugh. "That's a good

word for it."

"Yes, it's like a European circus from the 30's--not like

these affairs now with hundreds of people. The old kind--one ring,

where everyone did everything. Usually one family--the father the

ringmaster, the mother the horseback rider, the children on the

trapeze, maybe the uncles or grandparents as clowns. All running

around in a circle. Trying to make the audience laugh."

He uncrossed his legs and the smoking jacket fell open. He didn't

bother to close it.

"A tiny audience, you know, who probably hadn't seen anything

like it before. Sitting there with their expectations. And their

ultimate disappointment."

Plant was blowing smoke up into the room. It had the smell of

unpleasant incense. With his sagging belly he looked like a dying

Buddha. I hadn't heard what he said and asked him to repeat it.

"I said 'It passes the time.'"

"Oh yes," I said. I flicked an ash into a saucer.

"What do you do to pass the time?" he asked.

"Oh, I do a lot," I said. "I go to the theatre,

and I've got a lot of friends, and I'm working on my play--you

know what that's like--and I can't complain."

"You're lucky," Plant said.

"Well I guess I am," I said with some satisfaction.

"And what does it all mean?" he asked.

I was in no mood for metaphysics at that point. "What does

anything mean?" I Freuded. Then a forced laugh--"It passes

the time, like you said."

"Don't you ever get lonely?"

I could feel it coming and the last thing I wanted was to schtupp

an old man. I mean, it was Monday, after all.

"Sure, but doesn't everyone? And I've got my work."

"Your school?"

"No, that's kind of temporary. I've got my play."

It was getting darker in the room and I guess that meant that

it was getting darker outside. I couldn't tell.

"That keeps me busy."

Mr. Plant leaned back against a wall of books. His hair brushed

up and it looked like he had suddenly grown horns. "Tell me

about your play," he said.

"Well, like I said the other day, it's a new version of The

Importance of Being Earnest --that's set in New York--and the two

guys, Ernest and Algie, are chorus boys trying to get jobs and

make it with these two wealthy guys--and it's an update, see?"

"But what's it for?" he asked.

"What do you mean, 'what's it for?' What's anything for?"

"What are you trying to say?"

"I don't think I'm trying to say anything. Does everything

have to say something? I guess it's like your circus. I just want

the audience to have a good time." I was getting defensive,

I knew it. And also mad.

"Then what's stopping you?" he asked.

"You mean from working on it?"

"I suppose so. From making it permanent."

"Well you just can't give up a good-paying job and write

plays," I said. "And money doesn't grow on trees." I

laughed. "You should know that."

"I think that if you want to do it, then you should."

I was planning my exit.

"Well that's easy enough for you to say, but it ain't so

easy to do." A little bit of Brooklyn. "I mean, I can't

just walk into my Chairperson and say 'I quit because I'm gonna

write plays.'"

"Why not?"

I looked at him as if he were an imbecile. "Because you just

don't do things like that."

"I did."

"And look where you ended up." I had spoken too fast.

I had crossed over the line and I knew it.

I affected a laugh. "That didn't come out quite right," I

charmed.

Mr. Plant pulled his robe around him and seemed to shiver in that

stifling hothouse. "I guess you think I'm a failure, don't

you?" he said.

"I didn't say anything," I said. "And I got to

be going."

Mr. Plant looked at me; his eyes looked yellow and glassy. "I

envy you, Michael."

Nobody had called me Michael for years.

"You have all the things that anyone could ask for."

I couldn't tell whether he was being serious or ironic. "Damn

right," I said.

I stood up.

He didn't move.

"Have you found your rhyme yet?" he asked.

"No," I chuckled. "And Bonaparte doesn't fit, either." Our

common past. I was attempting a graceful exit.

"Maybe it does," he said. He held out his hand. "Good

luck."

"Yeah, you too," I replied. "I mean about your

friends." I guestured to the books.

He laughed again and then coughed. "Oh, we'll do all right.

And when I find the Pater, I'll get it to you."

"That would be great," I said. "I'm really looking

forward to reading it."

I took his hand--it was, as I knew it would be, rather clammy.

His forehead was moist.

"I hope you find your rhyme," said Mr. Plant.

How could anyone kiss those lips, I wondered.

"Yeah, thanks," I said, and, as they say in prison escape

films, I let myself out.

***

It was a particularly wet day, the Saturday after my birthday

in fact. I remember it because I felt I had to work off some turkey

at the gym--and it was on that day when the great event happened.

I'd spent my Birthday with my sister and her husband in Somerset,

New Jersey (he taught something dreary at Rutgers) and I'd scored

good at the Bike Stop the night before, and it was noonish or so

when I stumbled my several steps out of my building and onto the

Lincoln Center lunchtime pandemonium.

The cafeteria was closed so there was no procrastination possibilities

and it was up to the Weight Room. And there was Rocco. He was looking

down in the dumps and I thought that I was just the person to cheer

him up.

"What's the matter?" I said tactfully. "You look

like you've lost your best friend."

"Nothing," he said. He lay down on the bench and started

doing a press. "Paul's dead."

"Oh really," I said. "When did it happen?"

"Two days ago."

I was standing over him, ready to lift the weight. I was ready

to take my cues from him but he wasn't talking. "How'd it

happen?" I asked.

"Heart."

He thrust up the weight, straining. His biceps were swollen with

blood and I felt that old urge.

"Doesn't seem to be no relatives. People been going in and

out all day taking stuff. It's really disgusting."

"Yeah," I agreed.

I took the weight. It clanged down on its metal holder. "Feel

pretty bad, huh?"

Rocco looked at me. "Yeah, I suppose," he said.

It was my turn on the bench.

"You know, I liked him and all that," he said. "I

didn't know anybody when I moved in here."

Rocco was not paying attention to my weight and I barely lifted

it back to its rest. I swung up and around, sitting facing him.

"I mean, he'd have been all right if he could just have kept

his hands to himself." Rocco looked down at me and suddenly

smiled. "You know how it is," he said.

I smiled back. "Yeah, I know, only one thing on their mind." I

felt a bond in the air.

"I mean," said Rocco, "you'd think that when you

got to be a certain age, that kind of thing would cool down." Healthy

young animals.

"Well I hope I don't live long enough to find out," I

said.

"Me too."

We both laughed.

Then--I took the plunge. "You know, I've been working on

this show and I need someone with some dance experience to give

me some advice." I looked into Rocco's eyes.

"Oh yeah?" He returned the look. I could feel my cock

getting hard. "Like when?"

He was leaning against the wall. For a Saturday it was unusual

that there was no one else in the Weight Room.

I cleared my throat. "Like how about now?"

"Where do you live?"

"Down the block--in that little brownstone."

"The one in between the high-rises?"

"That's the one."

"Oh yeah, I always wanted to see the inside of that." He

looked at his watch. "Yeah, sure," he said. "But

only for an hour. I got a class at two."

We started downstairs.

"You got a shower?" he asked.

"Doesn't everyone," I said.

"Then let's shower at your place." He smiled and his

teeth dazzled. "Meet you downstairs."

I walked behind him down the steps from the Weight Room to the

Locker Room. We parted at the mirrors--and I fumbled with my combination

lock. I wondered if I'd drunk up all the Gallo brothers had to

offer from the night before. I changed quickly, stuffing my shorts

and jock into my gym bag.

Rocco was already downstairs. The lobby was filled with another

Perrier group of runners, their hair wet and the number cards on

their backs dripping.

"Let's cut out back," said Rocco.

We walked past the soda machines and the bulletin board. The back

exit was locked from the street-side but if you didn't pay attention

to the sign you could get through from inside.

"This an emergency?" asked Rocco, grinning and indicating

the overhead sign.

"You might say that," I answered.

The metal door opened with a bang. It was pouring outside.

"Let's make a dash,"Rocco said.

I pulled the door back on its hinges and slammed it shut. There

seemed to be garbage all around the sidewalk--and then I saw that

they were stacks of books. I looked at Rocco and we both knew whose

they were.

"It's a shame," he said flatly.

"I know," I said.

Rocco stood as if in a graveyard, and then gave the books a kick. "Stupid

old fuck," he said. "These probably killed him."

The books came tumbling down like a house of cards.

"Should have given them to the Library," I said.

And then I noticed a title that seemed familiar.

I leaned over. It was a gray book-- Studies in the History of

the Renaissance. Walter Pater.

"Hey, come on," said Rocco. "I'm getting wet."

I opened the book.

On the title page was some writing. It said: "Michael, you're

wrong. Take the ART out of heart and you've got nothing."

And something else that was blurred.

The rain washed down the page.

"Find something?" asked Rocco impatiently.

"No," I said, throwing the book back onto the pile.

"Then let's go," he said. "I've got a class."

And although I knew that Mr. Plant's place would now be empty

in that empty basement room, I didn't choose to fill it--but instead

went running after Rocco in that falling rain.

And, as Robert Frost once said, that has made all the difference.

|