Snow

in Summer:

LA, CA, 1963

by Helen Zelon

Peace, war, snow, New York and the inexplicable past explained.

"It snowed in New York, it said so in my book."

"...summer mornings stretched past noon into lazy, hot, white-sky afternoons."

My family landed in a spanking-new stucco bungalow in Holly Park Homes, in Gardena, California, after the construction of the San Diego Freeway leveled our first house. Our new house had been built along with hundreds of close cousins, all promptly sold off to a generation of young families striving to inhabit the American Dream -- three bedrooms, two baths, eat-in kitchen, two-car garage. Block after block, laid out on a grid as predictable and contained as the houses themselves. Controlling the interior environment, the terrain of memory and emotion, was the peculiar art my parents sought to refine every day.

Banked by the commercial avenues Van Ness and Rosecrans and the abyss-like 135th Street drainage ditch and sandy Rowley Park, the Holly Park kids biked, skated and ran, stripping hydrangea bushes for pretend-bride bouquets and cycling the endless loop of Ardath, 141st Street, Daphne, 139th Street as summer mornings stretched past noon into lazy, hot, white-sky afternoons.

The summer I turned eight my mother returned to full-time work and my life took on an air of autonomy. Our babysitter, Mrs. Mozell Rollins, an Ozark Baptist quilter, was so besotted with my toddler sister -- she of the long ringlets and liquid eyes, the spider-web eyelashes and sweet baby scents -- that I had comparatively free rein. Her benevolent indifference was my opportunity for adventure.

Summer afternoons, I hopped on my bike and rode the three-quarter miles to Purche Avenue School, where Mrs. Owens, the school librarian, waited -- for me alone, I knew it. Her first name was Charlotte. Charlotte, my mother's name! Her newest name, that is, after her birth name Tsirla and her nickname Cesia, which became Czeslawa when she went underground on Aryan papers, in Warsaw, in 1941. Now her friends and my father called her Cesia again, but at work, where my parents strove to keep the facts of their lives a secret, she was Charlotte. That she shared the librarian's name was an omen to me; Mrs. Owens stood in for the grandmothers whose faces I had never seen.

Every weekday was the same: Ride to school, get a book. Read the book overnight, go back. Biographies, novels, mysteries, series -- I ate the Bobbsey Twins and Nancy Drew for breakfast. Fridays were the best, because I could keep the book until Monday, and because Mrs. Owens often had something special put aside for me. One Friday in July, she gave me "A Cricket in Times Square," and my life changed forever.

New York! Lively, loud, vibrating city! People from all kinds of different places, with faraway names and strange accents confusing their speech. California was sameness to me, even then, and I did not fit in. My friends were blonde and fair, I am dark. They had patent-leather cases filled with blonde Barbies and red-headed Midges; my Auntie Celia gave me my brown-eyed, black-haired Barbie, a mini-misfit among her 11-inch peers. All my girlfriends had -ee names -- Vicky, Kathy, Debbie, Ruthie, Randi -- and I was stuck in the old world, with a name for aunties and old maids. My sister lucked out: she was named Edith, but became Edie (that --ee ending!) right away. Me, I am Helen, named for my grandmother, named for a dark and foreign place, for a time lost to fire and history.

Our neighbors bought their houses with GI loans. The fathers had gone to college on GI bills. Mothers stayed home, or worked as school aides or secretaries while Grandmas baked cookies and marshmallow treats. My parents were in the war, too, but not as soldiers. Now, they were American. They were engineers. Their work was rocketry and war planes; they knew top secrets and wouldn't tell, even when I begged to know just one tiny confidence. The friends that they played poker with on Saturday nights had numbers tattooed on their arms. Nobody, but nobody, knew from marshmallow treats.

"Cleanliness was how he survived the camps..."

If the land of the Beach Boys and eternal summer was not for me, I decided, I was not for it either. In New York, my book promised, you could be different -- dark, foreign. I realized I had been born in the wrong place, a tragic error in my parents' epic saga of war, survival, immigration and resettlement. The phoenix had risen from the ashes, yes, but had wound up on the wrong coast altogether. I was a New Yorker meant to be. I was eight, and I was moving East, as soon as I could manage it.

It snowed in New York, it said so in my book. Great white blizzards of snow, banking up on the streets, going gray with street grit, drifting into the ravines of Central Park. It confettied down the subway grates, and newsstand vendors had to bundle against the cold, damp white. It said so in the book.

On Monday, I rode to the library as usual, but didn't check out a new book. Instead, I renewed "Cricket," and read it through again, looking for a secret recipe for snow, a hint, any clue. At night, I punched my pillow up to make a bolster while I read. A tiny white down-feather pricked my cheek through the cotton ticking. I pulled it out, puffed it off my fingertip with an easy pah! of breath and watched it drift and settle onto my lavender bedspread. It lay there, balanced on a tuft of chenille, and the thought exploded in my 8-year-old brain. I had my plan.

The next morning, as usual, my father rose before the sunrise, with ample time for his habitual meticulous toilette -- shaving three times with a clean razor blade, twice against the grain of his beard and once, with it. Cleanliness was how he survived the camps, he said. He respected himself more than the others, and it showed. A fine appearance remained a principal talisman for success in his new country, where he could once again afford worsted wool suits and leather shoes with laces. His rinsed-clean shaving brush stood on the porcelain rim of the bathroom sink as my mother began her own catechism, of cosmetics and perfumes, that allowed her to present her professional self to the world.

Max Factor pancake makeup and rosy creme blush, light-blue powder eyeshadow, Maybelline pencil eyeliner, then mascara. Bouffant beauty-parlor hair tamed into a buoyant flip by a shower of Aqua Net hairspray. A burst of Chanel No. 5 -- my mother's homage to her idol, Marie Curie -- and Revlon's Love That Red lipstick finished her face. She bent across me, perched on the back of the toilet tank, to tear off a single square of toilet tissue. Carefully separating the paper along the perforations, she folded it precisely in half and blotted her lips. On school days, she often tucked that square of tissue into my lunch sack, a loving kiss from an absent mother. But now, in summer, she gave it to me. I tried to match my lips to hers, on the paper, and carry some of the vivid color to my own small mouth.

My father left for work in his sporty white Monza. My mother, after her customary morning repast of rye toast, smoked cod, coffee and unfiltered Herbert Tareyton cigarettes, welcomed Mrs. Rollins, then drove off in her big bronze Buick Skylark. In my mother's absence, Mrs. Rollins' distaste for me was unfettered by any concern for How It Looked. She took care of me, saw to it that I was fed and clean, but saved her love for Edie. Today, that was good: I was aiming for late afternoon, when my sister had her bath and when Mrs. Rollins, the mother of two grown sons, fussed with Edie's curly hair with the infinitely patient attention that mothers of men lavish on little girls' coiffures.

Vicky, Randi and I skated over to Thrifty Drugs for nickel Creamsicles. After, we played jacks on the sidewalk between the dichondra -- a peculiar, flowerless, low- to no-maintenance clover, planted in lieu of authentic grass -- on my front "lawn" and the narrow green strip that divided the sidewalk from the curb and gutter.

"Going to the library?" Randi asked.

"Nah," I said, collecting my jacks. "Not today." I went up my front steps, through the living room and past the bathroom, into my room.

"That you?" called Mrs. Rollins, from the bathroom. "Don't be tracking your dirt in here, keep outside! Not through the kitchen neither, the floor's wet. Go through the garage." She returned her attention to my slippery, splashing sister. Stealthily, I took my pillow and slipped outside.

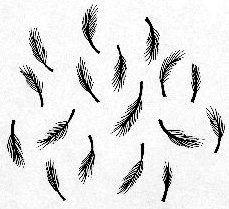

Our fenced-in yard had three elements: patio, driveway, and more dichondra, here a spongy, lima-bean-shaped green expanse, punctuated by the sprinkler heads that regularly kept it lush. I sat on the dichondra with my pillow, then stripped the pillow of its case. The tag tore off easily enough, but I couldn't rip the ticking; the fabric was stronger than me. I got my father's screwdriver from the garage and shoved it into the ticking. Hand clenched around its handle, I dragged the tool downward. A six-inch gash in the fabric began oozing feathers.

I put my hand in, wrist-deep. With a fist full of feathers, scouting fast for the babysitter, I spun around and threw the feathers up over my head. Feather-snow fell all around me. I took another fistful, then another, then two at a time, flinging each upward, turning face-up to receive the snow. Pretty soon, Randi and Vicky came by -- they had seen the "snow" billow over our backyard fence. They stuck their hands in the pillow and started throwing snow, too, and then all the kids came, all scooping up snow in handfuls from where it settled on the dichondra, throwing feather snowballs and wadding great piles of down into soft, hand-packed snow bombs. The aquamarine sky turned white with clouds of feathers, and we raised a racket, screeching and shouting and hollering in wild delight, because before too long, Mrs. Rollins came to the sliding-glass door in the den and stopped dead at the sight of us. "I don't know what to do with you wild ones," she scolded. To me, "Wait til your mother gets home."

"No one spoke of it ever again, until 18 Julys later..."

When the big Buick lumbered into the driveway, we were still playing in the dichondra, twirling in the flurries. My immaculate mother emerged from her car to see us, and her yard, covered in feathers, and seemed to stumble on the air. She regained her physical balance but went a little crazy, there on the hot driveway. Muttering through gritted teeth, half-Polish, half-English, she took me by the shoulders, shook me hard, shamed me in front of my friends.

"How could you do this?" she demanded. "Get rid of them" -- my friends -- "and clean this up." Then, she wept. My rock-solid, impermeable mother cried, there on her driveway in July 1963, ensconced in a perfect suburban world of her own devise, and her shoulders shook like mine had, only no one was shaking them.

"Clean this up," she said again, then lit a cigarette, and went inside.

Cleaning up the feathers was more of a challenge than making the snow had been. Scooping them back into the pillowcase was slow going. I tried the rake; all it did was kick up little eddies of feathers, which settled into the dichondra again. Meanwhile, my father came home.

"What are you doing?" he asked.

"Ask Mom," I said, sullen, on my hands and knees in the dichondra. He went into the house, then came out again, and said, stiffly, "Clean it up. All of it. You'll work until it's clean, you understand me?" I had violated something inviolable. What? And why didn't someone help me? All I wanted was snow ...

I found the garden hose and soaked the dichondra, thinking it would make it easier to get all the feathers out. I felt alone. And the wet feathers just stuck worse. I had to crawl every inch of that green mass, my soggy Capri pants bagging at the knees and butt, raking my fingertips underneath the dichondra's clover-tops down to the muddy stems, where the wet down seemed to wrap itself, intractable. It got dark. My father snapped on the yard light for me; no one spoke. I finished after 10 p.m.; my sister was asleep and my mother had a headache. My father sent me to bed. No one spoke of it ever again, until 18 Julys later, when my parents returned to Poland, and to Warsaw, where my mother was born and lived her youth. After a lifetime of imagining, I went, too.

****************

The Umschlagplatz, where transports of Jews were shipped East decades earlier, still received trains, including mine. Disembarking into the early morning haze, I realized I was stepping out of a station where others only stepped in. Better to find a taxi than dwell on that darkness, I thought, and headed out to look for a cab.

We settled into our rooms at the Hotel Warsawa and began to tour the capital once known as Paris of the East. The elegant "Cosmopolitan" restaurant in the hotel lobby was open for business but hadn't any meat; grocery stores were open, too, but bare, with long shelves standing empty or lined with limp cabbages and cauliflower.

A horse-drawn droshky drew us through the serpentine paths of Ogruzaski Park and the cobbled city streets until we reached a low, broken brick wall, the perimeter of what once was the Warsaw Ghetto, where my mother's family were moved when the war devoured Poland.

"We will walk now," announced my mother, aloud and to no one. My father paid the driver a fistful of zlotys as my mother strode off, down Mila Street, past Pawiak, the prison building where underground school was held, "only for boys." She looked around as if she could see through the Soviet-issue cinderblock apartments that stood on the old streets. Abruptly, she back-tracked to the block where she had left the burning Ghetto, through the sewers. She thought she found the manhole cover in the street, but couldn't be sure. It had been the middle of the night, she reasoned, and everything was up in flames. She couldn't be sure.

"...they wanted to believe, and what did we know?"

We traced bullet-grooved bricks with our fingertips as we wandered the alleys, looking for remnants of buildings that had burned in the Uprising.

"Here," she said to me, grabbing my wrist in her hand, pointing up to an empty slice of yellow-grey sky between buildings. "Here was the bridge where they shook the feathers."

"Ma," I said, pulling my arm back, "let go."

"When they took people out from the Ghetto, see, it was all very official, with the yellow papers and the official stamps, you needed the Nazi permission to go to the east. It will be for the best, they said, we will give you food, two loaves of bread and a kilo of margarine, and you will settle in a new place. People believed them -- they wanted to believe, and what did we know?"

"But the women did not want to leave everything behind; they took pots and pans, beds, quilts, pillows. This took too much room. You could always get goose feathers on a farm -- they thought that's where they were going, see? -- so they shook out all the feathers on the street, up from on top of the little bridge, and packed everything else away. So everything was under feathers the days the transports left." She looked at me again. A shudder rose through her, until she touched the hollow of her throat and pushed back a wavy lock of hair. Then, she stopped talking.

please email ducts with your comments.