| |

"The West is the best." Jim Morrison

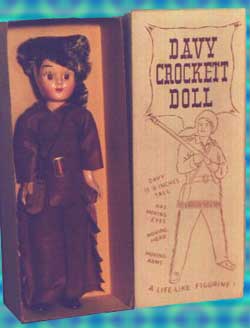

As a fledgling historian, I’ve been plagiarizing some very interesting work lately on the origins of that bizarre and elusive national psychosis known historically as "The '60s." Much has been written. Even more has been televised. Some evidence resides in the recorded annals of radio and some is still on 8mm film waiting to be developed. Among the causes suggested for this national and personal turmoil: a downward shift in demographics combined with an upward shift in the economic cycle, the pill, drugs, anything that happens on the pill or on drugs, the war in Vietnam, Las Vegas architecture, the writings of Herbert Marcuse and Norman O. Brown, and a delayed celebration for the end of World War II. No one, however, except for Bleatman and Himmler (1999) - from whom I cribbed this report - has stumbled upon this central fact: the generation that participated in the social, cultural, political, psychological and emotional uprising commonly known as "The '60s" was influenced in early childhood by the national mania over Walt Disney’s "Davy Crockett." This phenomenon had deep and long lasting unconscious effects. According to "The Davy Crockett Craze," by Paul F. Anderson (R&G Productions, 1996) the nation’s mania over the then all but forgotten buckskin clad, coonskin clad, moccasin clad mensch (marvelously portrayed by Fess Parker) began the week of December 16-22, 1954, just days after ABC broadcast episode one, "Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter." The continuation of this epic saga came in January of 1955 with the politically sensitive, "Crockett Goes To Congress" and the following February with "Crockett at the Alamo." Hunger for Crockettania, was sudden and almost as voracious as the nineteenth century hunger to steal any land then occupied by non-whites. Anderson writes that the craze ultimately meant sales of $300,000,000 in Davy stuff or over $1.8 billion in 1996 dollars or as Crockett might have said, "Many pelts." It was oddly brief, however. According to Anderson, the love of things Crockettish lasted only about a year with some residual effects into 1957. Disney himself is quoted as saying he was taken by surprise at the uproar. Had he foreseen it, Disney said, he wouldn't have killed off his hero in episode three. The entire series, writes Anderson was re-broadcast later in 1955 to make the most of the sudden euphoria and then two more episodes were added, broadcast in 1955 and early 1956. Naturally, massive plans were undertaken to extend the Crockett story, but soon the craze cooled and Parker was hustled off to be utilized in Disney feature films. During those Davy days, the Crockett character was viewed as exemplifying all that was good about wholesome, solid, mainstream American values, including the fact that he’d helped cause several million Latinos to ask, "Hey, who stole northern Mexico?" Disney was known as an active Conservative who wanted to promote a marketable and mesmerizing American hero. When a Crockett backlash began - Crockett's real story bursting into public awareness with a Clinton-Lewinski lewdness - no less than arch-conservative William F. Buckley railed that the debunking campaign was partly due to "resentment by liberal publicists of Davy’s neurosis-free approach to life," (quoted in Anderson.) Yet, years later, as the children of Crockettaria came of age, it seems Crockett’s values fueled not the crumbling edifice of the conservative mainstream, but the burgeoning counter-culture which had unconsciously adopted Davy’s values, haircut and mode of dress. As Freud wrote to Jung in 1928: "If there’s ever such a thing as television, don’t watch too much and don_t sit too close." First, Crockett’s physical presence. As stated in Bleatman and Himmler (1999), "Only an idiot could miss the similarities between Davy Crockett’s clothes and those of various counter-culture sects such as hippies, yippies and diggers. Long hair, fringed jackets, wide belt buckles and moccasins. It’s as pronounced as Paladin's influence on current New York fashion." But the influence doesn’t end there. A careful analysis of the three Davy Crockett episodes reveals actions and dialogue that had the unintended effect of driving millions of young people wild in the streets, forcing an overhaul of contemporary America. Crockett’s most famous historically verified quote echoes through the ‘60s and even up to the more recent era of post-modern commodification. Said Davy: "Be always sure you're right, then go ahead." Had he bypassed the Alamo and thus lived until 1968, Crockett might just as well have stated: "Dig your head, do your thing, be your thing," as did Abbie Hoffman or the more abbreviated, "Do it," in the words of Jerry Rubin (later to be bastardized into "Just do it," in the name of Nike.) Likewise, the popularity of the guitar--which was later to make such a strong impression on a bewildered generation - is foreshadowed by Crockett’s sidekick, Georgie Russell (played to a toady T by Buddy Ebsen). Throughout the series, Georgie follows Davy on horseback literally narrating Crockett’s every move with a new verse of "Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier." Davy rides his horse and hears Georgie sing behind him, "Davy rode a horse." Then Davy crosses a stream and hears behind him, "Davy crossed a stream." Then Davy shoots his gun and hears behind him, "Davy shot his gun," all to the ballad_s well-known, hypnotic tune. This clearly speaks to the importance of music during the period known irritatingly as "The 60's," but one wonders when Crockett will turn in his saddle and say, "Hey, Georgie. Why the hell don’t you SHUT UP!" In fact, quoting a verse of the Davy Crockett Ballad referring to the first episode, ("Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter,") the song itself proclaims an outlook that would make its way more than 130 years into the uncertain future: "He give his word and he give his hand

That his Injun friends could keep their land

And the rest of his life he took the stand

That justice was do every Redskin band." If we quickly but gingerly skip over the ugly, hateful, disgusting, paternalistic and patriarchic racist references to Native Americans, this beautiful acceptance of "Indian" culture was to become an important part of the decade known increasingly as "The ‘60s." So was resistance to authority. This is a mainstay of Crockett’s outlook as (again, episode one) he refuses to bow to the crushing power of the U.S. Army, following only his own creed and what is good for the welfare of his men. Interestingly, the Army itself is pictured as a top-heavy, clanking, stupefying formal military organization which is no match for the wily, guerrilla fighting Creek Indians. American soldiers can only avoid ambush in the jungles of Tennessee if helped by Crockett, a man of the woods. As Bleatman and Himmler write (1999) "Only an idiot would miss that obvious critique." This strong theme of rebellion against authority includes not only the Army but extends to the political establishment, as well. In episode two ("Crockett Goes To Congress") the Davy-depiction is of a man who: "Went off to Washington and served a spell,

Fixing up the government and laws as well.

Took over Washington so I hear tell,

And patched up the crack in the Liberty Bell." This approach, including the mention of Crockett’s revolutionary leanings ("took over Washington") mark a clear connection between the latter day counter-culture and what obsessed young minds watching TV in the ‘50s regardless of the intended purpose. Crockett’s presence in Congress is marked by humor, drinking and a decided lack of "speechifying," a stated refusal to dress properly, a distrust of campaign promises as well as a stated fight for the small farmer (read "commune.") In his introductory speech to Congress, Crockett asks that whiskey be allowed in the congressional chamber and states that his father is the toughest man alive "and I can lick my father," a clear pointing towards the Oedipal conflict which so marked the period known by some as "The '60s." Also in Washington, Crockett criticizes President Jackson face-to-face, then meets up again with his former military commander, Tobias Norton who is presented as so much the martinet it's as if he sat down naked on a long steel rod. Both Norton and Jackson double-cross Crockett attempting to secretly pass a bill that will rob land from the Indians. Learning of this government deception, Crockett shouts at Norton, "Here_s what I think of your kind of politics!" then punches him as the uptight Norton goes careening floorward. Next, during an impassioned plea to Congress, Crockett demands that Washington hold sacred its promise to the Indians and blames himself and his political colleagues for letting the bill get so far. "We all have a responsibility to this strappin', fun-lovin', britches-bustin', young bar cub of a country," declares Davy. This speech might just as well have come out of "Revolution For The Hell Of It." Finally, searching for a peaceful plot of land, "the man who don't know fear" wanders to Texas and ends up buying the farm at the Alamo. This final episode is largely a battle scene, the Alamo situation depicted in mythic manner as the brave fight of a small band of heroes against an overwhelmingly large and evil force. On the way to the fight, Crockett makes a nearly Kerouacian statement about his nomadic ways saying, "A man keeps moving around his whole life looking for his particular paradise." And the night before he goes to Crockett Heaven, swinging his rifle against his enemies, he is pictured singing a quiet ballad called "Farewell to the Mountains" in which the word "bosom" is heard as a metaphor for "soul." According to Bleatman and Himmler (1999) "Only an idiot would miss the fact that this was the first time the word "bosom" was heard on television by an entire generation which couldn_t stop snickering until it started breathing heavily over Annette Funicello." Thus, the sexual revolution. This final episode ends with a shot of Davy Crockett_s Journal, the words he_s written shown on screen: "March 6, 1836. Liberty and Independence Forever!" More could be said, much, much more. And even more than that. But to go on would be to violate the backwoods brevity of Crockett himself, a man of few words who didn_t learn until age 30 that the word "bar" was actually pronounced "bear." This accounted for his famous hand-to-hand match with a grizzly whom he openly claimed had stolen a very expensive jug of his best corn "likker." And so we must end with paradox: No Crockett, no '60s. No '60s, no drug culture. No drug culture, no music (which we’ve been hearing now, over and over, for what? almost 40 years?) No drug culture and music, no widening of consciousness and creativity, no women’s rights, no gay rights, no volunteer military, no computers, no Internet. No long hair, short skirts, or modernity. Ergo: No Crockett, no America. We'd still be a nation of short-pants and clip-on bow ties, fighting in Vietnam.

email us with your comments. | |  |