|

The cacophony

got louder, and mothers abandoned their household chores, bringing

their infants with them. My mother and I joined them, and together

we listened to the unseen roar seemingly far away. I was three years old, my mother

holding my hand as we stood in the street outside our walk-up flat, that noise groaning

and thunderous in the summer-blue sky. Skokie, Illinois, declared all businesses closed

to celebrate V-J Day. If there was a phobia for the fear of looking at the sky, then that

day brought it on. The tension fueled by the interminable waiting to see the source

of the noise had been my first brush with paranoia. Normal anticipation transmogrified

into outright paranoiac reaction. Fear zinged through the others, or so I reckoned, and

my neurons spread out their receptors, soaking angst up. My anxiety translated into unreasonable

distrust and suspicion. What invisible bogeyman was about to slay me? If Ezra

Pound's line about poets being the antennae of the race held true, I would beam paranoia

for a thousand years.

I

should not mislead you: that was not my first memory, but second.

My first one was strolling through a park, again holding on to my

mother's hand, seeing bright, touchable flowers planted along the

perimeter of the serpentine walk. I saw those blooms as a gift.

The blossoms were my friends, and together we were in the sweet

bead of life. There had been no linkage between the two memories.

The continuum had been severed. One memory brought joy, the other

misery. I

should not mislead you: that was not my first memory, but second.

My first one was strolling through a park, again holding on to my

mother's hand, seeing bright, touchable flowers planted along the

perimeter of the serpentine walk. I saw those blooms as a gift.

The blossoms were my friends, and together we were in the sweet

bead of life. There had been no linkage between the two memories.

The continuum had been severed. One memory brought joy, the other

misery.

Some geniuses proclaimed memories while

in their mothers' wombs. Harry Crews addressed what happened ten

years before being born. We all knew Tristram Shandy. Gifted

Baudelaire wrote, "It is from the womb of art that criticism

was born." The Latin root for critic was decide and judge,

something I had done ruthlessly ever since V-J Day. Had I smelled

with my pink nose those flowers in the park, Les Fleurs du mal?

The flowers of the macabre. Had I breathed in pessimism from those

flowers? Would every step I took become in truth the Danse Macabre?

Baudelaire explored his isolation and melancholy, his attraction

to morbidity. Me too, commencing V-J Day. But I spoke Midwestern

English and never smoked opium.

And I had not forgotten his Spleen de

Paris. Spleen meant bad temper and spite, other shrewd attributes I manifested early. The Potowatomis, who lived

in Northern Illinois for centuries, had a name for "swamp": skokie. Since I was

in pre-suicidal mode, I had nothing to gain by doing away with myself as had depressed Robert

Frost when he entered the Great Dismal Swamp along the Virginia-North Carolina

border region. But in the spleen of Skokie, the erstwhile swamp, my life began. Yeah,

I nitpicked those literary allusions and etymology, but that was precisely how my twisted mind

best expressed earliest confusion.

Very soon, overhead, controlled pandemonium

enveloped me as I craned my neck and looked up from the now crowded street. Planes clothed the sky with

a booming presence, gathered not like storm clouds but a hungry force unfathomable to

me. B-29s seemed to hover in place directly above me, stirring and brooding like nightmares

unwilling to let go.

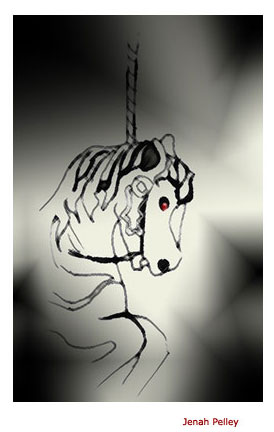

Eight years later, I did have nightmares

of a mechanized racehorse suddenly veering toward me. I must have seen racetracks in Hollywood movies on TV.

A Day at the Races? I was among onlookers at the final turn. I was horrified,

the menacing horse even grinned, galloping with intent to kill me, its single purpose. I

stood helpless and immobilized, stranded in fear because it was going to grind me up

in tiny shards with its bleeding, bluish-gray succubus teeth.

Those planes overhead would loll perpetually

above me. I knew that to be true, even in my formative brain. Only in college did I learn that two B-29s were

responsible for two atomic bombs, one each dropping death on two Japanese cities. America:

evil-stake mean. The easy regurgitation of that history had not placed me on high moral

ground, supposed by Americans who privileged that obvious historic perception until

only their sham purity shone through as a hokey mantra. I stood beneath total mobilization

of air power with casually dressed non-combatants, mothers with bare legs and wobbly,

gooey children staring upward. I had no memory of my first vomit, but it could

have been then.

It had been a moment when awe and surprise

trumped perspicuity. No one was precocious back then. Or so it seemed. Or purported to be as in

our current era. Perhaps if Charles Bukowski had held my hand instead of my mother (quit visualizing

that), his insight that losers knew the true meaning of life while victors

had no clue would have sounded alarums throughout the land. Why had the U.S.A. evaporated

Nagaski? Why the super-abundance of cruelty? Why multiple genocide? Why the second

bomb and my concomitant need for the second memory?

Somewhere in my toddler biology, as if

that winged formation had given me a deep tissue massage, kneading the temporal lobe where the hippocampus

was located, I would always remember that day. For me, the whole point of life would

be authenticity, literally to make more of life. Whenever I struck out for abundance, more,

I plunged into the swamp like a flawed amphibian, "not waving but drowning"

as Stevie Smith wrote.

Those B-29s would never be an abstraction,

but lacerated like heavy industrial machinery into my mind.

They were not a stale, dead metaphor.

No. We walked back to our apartment, my mother trying to get me to scale the steps of the wooden staircase.

In the kitchen, she spooned me Gerber's as I sat in a highchair next to the refrigerator.

I would not eat, spitting it down my chin because I was not hungry. Those low-flying

bombers over my hometown wrecked my appetite. Much more to life than eating, I thought.

The world would always be about power and domination. How would I dare to

dethrone those two gigantic and dreadful kings? Or would I challenge them at all?

From my father's lap I saw through the

window a white house from which the orders for the second memory emanated. Not the White House, but the little

garden shed across the street and down the block. I heard many news broadcasts ceaselessly

mentioning the White House, and I took the newscasters to mean that cutesy white

house. Apparently, everything important in the world came from the tiny white outbuilding,

a minor citadel I saw whenever I sat wiggling around on Dad's lap in the evening.

I smelled Dad's tobacco effluvium and

nicotine breath, ugly and grim, many parsecs removed from the fragrance of Signor Giacomo Rappaccini's garden

in Hawthorne's story. Nevertheless, the white house and Dad's odor coalesced as

anecdote rather than art itself. A large brown radio near the comfy chair emitted male voices

talking about that sanctum sanctorum, the white shed. I only saw two wooden walls,

though I suspected it was larger by far than my view allowed. It had to be. Its emissaries

announced gravitas and tension every evening whenever I sat with Dad. A lot went on

inside that garden edifice.

White-thick dragon smoke blew from Dad's

mouth and nostrils, its smell a cue for listening to the radio and watching the white house. Perhaps someone

might walk out from the rear, then climbing up the flight of stairs to our apartment,

explaining every- thing. The flowers, the second memory, Dad's keen attention to those

strong unseen, erudite voices, that clean, well-maintained white house in which

I never inspected for myself---all would be connected if only a single representative

stepped out the backdoor and intoned all secrets to me. However, no grand unified theory

emerged. I had neither the ambition nor courage to seek out whoever lived inside the Skokie

white house.

Shortly, Dad would take me to their double

bed where I slept until they went to bed. Then, Dad moved me into the dining room where I slept on a folding

bed. Light, shadowy and pulsating, receded as he carried me from their bedroom

before I fell asleep anew. Dad never picked me up without my waking up, if only slightly.

I thoroughly enjoyed that crack between wakefulness and oblivion. It imparted

a thrill, something like a drug, where I left hard reality behind, joining the world of indeterminate

shapes and rearranged boundaries. The time it took traveling from their bed

to mine, from Dad's arms holding me to the moment he released me onto the dining room

bed: I wanted those seconds to stretch forever. I craved permanent amazement.

Once, during sleep, I rolled against the

wall and the bric-a-brac as well as the shelf crashed down upon me. I screamed immediately, swift reactions being

a major trait. Dad came almost as fast as my crying started. That was the first time

I felt someone caring for me. It established the first consciousness of my consciousness,

qualia as neuroscientists called it decades later. But from that crisis I would forever me

in need of a whole lot more vigilance than he could supply. No matter the haste and genuineness

in which he comforted me, I always felt it was not enough.

Lacking élan, it seemed stilted and left

behind a bad taste, like straight vermouth, that word from Wermut, German for wormwood. In later life I used to have

a cheap print of The Absinthe Drinkers by Degas tacked on my wall. Every time I looked

at it, I traveled through a Star Trek wormhole ( puns allowed only as atheists spoke

of God to explain why God was nonexistent ) and into my past, feeling cold and bitter.

He turned on the light, and I saw fear

in his eyes. And he sounded alarmed. Both emotions I absorbed, made them mine, never understanding that he

had reached out to protect me. Instead of seeing the heroic, something to be cherished,

it became an antithesis which I could never synthesize. Dialectics, whether Greek

to discover truth, or Kantian to experience the soul, Hegelian to reach higher truth,

the state, or Marxian dialectical materialism to understand conflict and contradictions:

these never penetrated my outer shell. My pod would remain intact until Kevin McCarthy,

of Invasion of the Body Snatchers fame, rose bodily from his grave.

I went to sleep immediately after Dad

cleared the debris from the bed. I translated deep affection into

fear and panic, love to be scorned in favor of the other two verities.

I woke up the next day feeling changed, a discoverer not of a leap

of faith and love but one who had encountered shame. I would not

look into his eyes before he left for work. The previous night's

falling clatter led me away from his natural glory. I had defiled

it with a painful feeling of unworthiness. The Dutch word was veeg,

cowardly.

I hate pedantry as much as you, but obsessions

cannot be overcome by rational thought and common sense. Get over

it, for chrissake. Pedagogue, a Greek word denoting a slave who

accompanied a child to school: a boy guide. Bilingual semantics

were included here to demonstrate worldliness, initiated by Night

of the Descending Bric-a-brac when I shunned love, acquired self-abomination

and began intellectually questioning everything about my dad. "A

true saint is a profound skeptic; a total disbeliever in human reason,"

wrote Henry Adams. I would become a philosopher of en lontananza---distance

and remoteness---skeptical forever and ever. Amen. Or I could have

been back then on the road to schlemiel-hood.

And that "passage" stuff about

primal events. Had not all children leaked shit from their noses

when leaving home for the first time? I had my fingers pried away

from the base of the radiator by my mother and a perplexed, edgy

cab driver so I would take his taxi to nursery school. Other kids

had similar anxieties, no? No. My resistance was fierce, indomitable,

and my four-year-old self wanted to kill that cabbie-father with

my bare hands, without moral restraint. Not a temper tantrum, but

a cri de coeur, defiance in the teeth of illegitimate authority.

Lucky that guy let Mom do most of the grunt work, pleading, coaxing,

and finally they dragged me down the steep stairs into the back

seat of the cab, with me wailing dung-tears all the way to school.

What I lacked was the repressed memory

of Bruce Banner, the Incredible Hulk, who in the future would knock

his father backwards, cracking his skull on the tombstone of Bruce's

dead mother, slain by his father. The hapless cabbie was a poor

stand-in for Daddy Dearest. ( DD ruled the throne in Skokie as Cardinal

Richelieu held sway over France during Queen Marie de Medici's reign.

But that was an analogy I would have to abandon, simply because

of its self-evident obscurity, though much fun nonetheless. )

The tombstone-death of Brian the Father

transfigured my life, recurring in vivid dreams of DD clunking his

melon hard on a hardwood floor, dying with streaming blood everywhere.

And that was before I even knew about Bruce Banner and the Hulk.

Flash-forwarding fourteen years, I had all essentials for my own

little Dien Bien Phu, the battle in which the Vietnamese defeated

the French, i.e., when it came my turn as a colonized son to finish

off Dad in another Chicago suburb not far from Skokie. Like the

Hulk, I wanted Mom for the alpha-parent. Bruce's father had been

an atomic physicist who gave his son Bruce a mutated intelligence

derived from Brian's exposure to gamma radiation. The comic book

mutation became my dad's real life occupation, accounting. How I

despised my father for his recondite skills as a number-fucker.

A lame high school teacher hypothetically

assigning a writing exercise: Describe Your Very First Day In School.

I would give her seven words: THAT'S WHEN I KNEW DAD MUST DIE!

That damn paper towel. Why had the teacher

done that to me? My social acquaintances had been limited to my

parents, and I had no peers. Perhaps the kids in our building all

sucked or they found my infantile patter boring and unproductive.

Maybe Dad protected me, like the weird looking girl sequestered

from the world that sweet and kind Gelsomina came across in La Strada.

I had no goofy index delineating someone who needed prophylactic

sheltering forever. I harbored an intuitive substandard ranking

of myself.

When the harridan had had enough shush-shushing

me for nonstop talking, she pinned a paper towel around my face

and told me to BE QUIET. To this day I had always heard her say

in my carping inner monologue, SHUT UP, two little words approaching

profanity in the Sparling household. Taboo words, those. Where was

the ACLU when I needed them? The punk-ass fishwife had censored

me, tortured me for the sake of general classroom harmony. Law and

order: my ass. The obvious conclusion was that doing standup routines

would not be a career option. She had cut off my balls. If my parents

had aspirations for me going to Italy and becoming a WASP castrato,

my earnings to be sucked up as John Agar had stolen all of Shirley

Temple's child-loot, nursery school's "Mrs. Hoess" ( the

real life Mrs. Hoess lived with her husband at Auschwitz while he

murdered innocent Jews ) quelled that notion.

Hand-glassing. Had anyone ever done that?

Alone in the living room, I looked at the window pane, and wanted

to express the parallel. I thought that an exquisite gesture. Euclid's

Postulate 5 in Elements first defined it. Addison, Pope, Swift,

Browne, Shakespeare, and Locke used the word to express humanism.

My Puritan body would put it into practice. Praxis, not theory,

would distinguish me from everyone. I stood as far from for the

window as possible, then ran full speed, proposing to perfect the

Abrupt Stop Maneuver on the fly. Merging the palpable with the hidden,

I wanted both worlds joined at my palm. I knew in my heart I could

do it. How else to explore both sides of glassiness? Defying gravity,

overthrowing Newton, making myself known in perpetuity, having women

look fondly and adoring at me as a real player, an innovator, an

American Dreamer: I failed. I was stuck with the mundane.

My enthusiasm, its momentum, the glee

of freely giving myself up to the aeronautics of being, overwhelmed me. I tried to stop with the flat of my hand

halting at the pane's first touch. But I broke through, nearly falling out the second

floor, glass bursting and fragmenting like guerrilla landmines. I screamed and Dad came out

of nowhere. He asked what I was doing, breaking the window, hadn't I any sense. I had

only one cut on my palm. He bandaged it, and I simpered in a rocking chair. Shortly,

Mom gave me chocolate pudding to distract me from the would-be triumph turned

disaster. That was the first time I ever sulked.

I would not re-enact the source of my

failure for fifteen years. While drunk, on fraternity row, I felt the demiurge: to break a window of an opposing

frat house, a corrupted re-enactment of the Skokie episode. Again, I had no chance

for uplift or encouragement. My desire would not correlate with actuality. What

I sought was to be an eponymous creator: Sparlingean, an aspirer of parallel world convergence.

Howling Wolf had a line, "I wanted water, but she gave me gasoline."

I thirsted for recognition, but received only another cut hand. Growing up would

always be an illusion.

|