|

One night

my father died and left me with both a store and my mother. Never

a man to waste time, he didn't linger. He went to bed and fell asleep

quickly as always. Only this time he didn't wake up. It was Thursday,

October 22, 1981.

Three weeks later, when I noticed

I was still alive and my father was still dead, it became time to

turn my attention to the store, that tiny hosiery and dry goods

domain where my dad, Daniel Potkorony, had reigned unopposed for

almost half a century. The debate began. What should we do with

it? All of November we anguished, dazed, looking to others for help

with a decision I never imagined having to make. My mother's cousin,

Moishe, who was also our lawyer, advised us to get rid of the place,

to liquidate and walk away.

"You've got enough headaches."

He was right. I already had

a full schedule working part time as a School Psychologist while

I finished my doctoral studies. I certainly didn't want to give

that up to become a shopkeeper. I had no husband, no siblings, and

neither of my children were interested in selling socks and underwear.

To Eugene and Nancy, the store was a relic, a place I insisted they

visit occasionally, so their grandfather could see them.

He enjoyed offering gifts of his merchandise

to his grandchildren. "Do you need anything?" he'd ask. "Go ahead,

take something. Don't be ashamed."

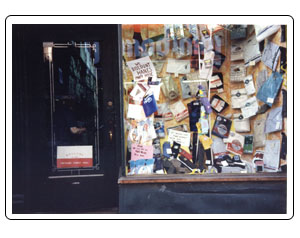

The three foot tall, hand-painted

sign above the store window announced to the world that this was

the site of Universal Hosiery Company, a grandiose choice

in names for an uneducated immigrant from a small town in Russia.

But other than his origins, nothing about my father was small. He

measured five feet ten inches, just a bit above average for his

generation, but he was a commanding presence. Broad shouldered,

with a solidly husky frame and a booming voice, he rearranged the

air when he walked into a room. He could crack walnuts with one

hand.

The store was housed on the

ground floor of a vacant tenement building on Orchard Street, the

Lower East Side of Manhattan. It occupied a space six feet wide

and eighty feet long. Both sides of this rectangular sliver were

lined with khaki green shelves made of steel. They stretched from

the rubber-tiled floor all the way up to the tin filigreed ceiling.

Every shelf was filled with boxes of merchandise neatly stacked

in rows, mostly men's socks, underwear and pajamas. A small section

in the rear was devoted to women's panties and stockings. Customers

were served from a wooden counter that bisected the front half of

the store, and sales were rung up on a 100 year old NCR cash register,

with a brass handle that needed a full circle turn before the cash

drawer clanged open. Receipts were hand written on an invoice pad

that documented a purchase from "Universal Hosiery Company, The

House Of Bargains." The store was housed on the

ground floor of a vacant tenement building on Orchard Street, the

Lower East Side of Manhattan. It occupied a space six feet wide

and eighty feet long. Both sides of this rectangular sliver were

lined with khaki green shelves made of steel. They stretched from

the rubber-tiled floor all the way up to the tin filigreed ceiling.

Every shelf was filled with boxes of merchandise neatly stacked

in rows, mostly men's socks, underwear and pajamas. A small section

in the rear was devoted to women's panties and stockings. Customers

were served from a wooden counter that bisected the front half of

the store, and sales were rung up on a 100 year old NCR cash register,

with a brass handle that needed a full circle turn before the cash

drawer clanged open. Receipts were hand written on an invoice pad

that documented a purchase from "Universal Hosiery Company, The

House Of Bargains."

"Before you decide what you're

going to do," we were told by our accountant, also a cousin, "you

have to take inventory."

"Inventory?"

"Yes. Inventory. You have to

count how many dozens there are of each item. We need to get the

net worth of his stock."

I listened carefully enough,

but down deep, where my soul lived, I was convinced this was all

a dream. Any minute now my father would suddenly jump out from where

he was hiding, and we'd all laugh at the joke he'd played on us.

After all, at his funeral service, a close friend seeking to comfort

me had said, "If your father could die, Sandra, then anyone could

die."/p>

It was the middle of November

before we gathered enough courage to physically visit the store.

While my father was alive, no one ever set foot on the premises

without his permission, nor was anyone else privy to the operation

of his business. It was basically a one-man show, with limited assistance

from his brother, Morris, who worked there until his death in 1978.

Then my uncle Joe, a retired postal worker, was recruited to unpack

stock and stand watch at the front door whenever my dad needed something

from the back.

In addition to the main selling

area, there was a separate storage room where out of season merchandise

was kept. I knew it was there, but I'd never actually been inside

it. With my mother following closely at my heels, I pushed open

the creaky wooden door and peered inside. The only light in this

windowless room came from a bare bulb dangling in its socket from

a ceiling wire that swayed when I pulled the string to make it go

on. Huge cartons stuffed with cellophane-wrapped packages of thermal

underwear and flannel shirts were stacked against one side of the

room. Shelves on the opposite wall were piled high with old ledgers,

bank statements and boxes of receipts. We were looking at the archives

of Universal Hosiery Company, which went back to 1937, the year

the store was born.

Ignoring my mother's protests,

I climbed up an eight-foot ladder to get to the top shelf. She stood

on the ground beside me, tightly clutching one side of the ladder,

convinced I would fall, but also wanting to know what was there.

I found an old suitcase with two bottles of liquor inside, an unopened

bottle of Crown Royal and a half empty bottle of Chivas Regal. Nothing

paltry about my dad's taste in alcohol.

"Throw it away," my mother

ordered. "It must be from a long time ago."

"Sure, Mom." I didn't tell

her I also found several unused condoms in the suitcase, and they

looked pretty new.

We could have hired someone

to take care of the inventory, but that would have been like opening

my father's bedroom to strangers. We wanted to examine everything

ourselves first, our curiosity as great as our reverence. So, the

day before Thanksgiving I bought a thick spiral notebook, a box

of black marking pens, and we began. Not an easy task for one middle

aged daughter and her tiny, elderly mother. My mom had never stood

much higher than five feet, but she'd shrunk as she aged. By the

time my dad died, she was barely four feet ten inches. If I knew

almost none of the details about what my father did, my mother knew

less. She'd never in her life even written a check.

My uncle Joe helped us, since

he was familiar with the merchandise, and my children spent most

of the Thanksgiving weekend there, which gave us a chance to be

together without the pretense of celebration.

Henry Semel, one of my father's

friends who had once operated a similar business, showed up uninvited

to offer assistance. A short, chubby man with a few strands of dyed

black hair combed sideways over his scalp, he wore a large gold

pinky ring and constantly chewed on an unlit cigar.

"Don't worry, Rose, I won't

light it," he assured my mother. "I know you don't want me to smoke

this here," he added, probably hoping she'd contradict him.

"You're right," she replied.

"Cigars stink. Danny never liked them."

Henry turned out to be a big

help, but whenever we tried to thank him, he'd wave away our gratitude

with the explanation he really owed a lot to my father.

"Do you think he owes Daddy

money?" my mother whispered one day, when his back was turned. "I

bet he does," she added, ever suspicious of kindness.

There was no way to know, and

I didn't care. Henry gave me my first lessons in how to run a retail

business, and for that I was grateful.

My mom took it upon herself

to bring lunch for everyone, usually cream cheese and jelly sandwiches

on rye bread, a thermos of coffee, and slices of danish.

"It's time to eat," she would

announce, promptly at noon. There was enough for everyone, but I

was the one she pressured most.

"Soon, Mom. I just want to

finish this shelf."

"You need to eat," she would

entreat. The boxes can wait."

If urging didn't work, she'd

set napkins out on the counter, unwrap the sandwiches and pour the

coffee. "You better come right now. It's getting cold."

It was easier to eat than argue.

When she wasn't feeding us,

she followed me around watching closely as I opened each box of

merchandise and tallied its contents.

"Are you sure you know what

you're doing?" she'd ask, skeptically. "Daddy didn't used to do

it that way."

When I became irritated, which

was often, I'd challenge her, "How do you know?"

She'd shrug and say, "I know

better than you."

We spent the first week on

socks alone. I learned to recognize all-cotton English ribbed socks,

as distinguished from cotton blends. There were orlon, nylon, and

wool socks, dress and sport socks, thin socks, thick socks. And

each type came in different lengths, anklet, mid-calf and over the

calf, or "otc's" as Henry called them. Just when I thought we'd

completed all the hosiery, I found a few cartons of boys and infant's

socks. When I closed my eyes at night, boxes of socks continued

to float across my field of vision.

Men's underwear was the next category.

My father had a huge stock of briefs, boxers, undershirts and tee

shirts in three brands, Hanes, Fruit of the Loom and Munsingwear.

I studied them all. It was fun to learn about men's underwear–also

titillating. Munsingwear, for example, makes a brief with a pouched

crotch and a fly that opens horizontally. I'd never known a man

who wore such a brief. Not that I'd been intimate with a lot of

men. There was Allan, my husband for twenty years–he wore boxers–and

a scant few others in the six years since Allan and I had separated.

Several months before my father died, I'd ended a relationship with

an Israeli named Yossi. He wore colored briefs.

I drove my mother home each

evening, and we'd talk about what to do once the inventory was complete.

The more familiar we became with the contents of my father's store,

the harder it was to contemplate letting go of it. His soul still

lived there.

"If we could only get a man

to take over the business," my mother said, looking at me hopefully.

"I wouldn't mind coming in to work. What else do I got to do? Stay

home and stare at the walls?"

I convinced myself it was my

duty to keep the store open for her sake, and talked to practically

every male relative about buying the place, renting it, or getting

involved in any way that would allow my mother to continue working.

No one was interested. I even propositioned Henry, although my mom

wasn't too happy about that.

"Why do you need a man to take

it over?" he asked. "You're an intelligent girl. Why don't you run

it? Hire a man to help with the heavy work. It'll give Rose something

to do, a place to go every day."

But what about me? I already

had enough places to go every day. I didn't want any new places,

any more responsibilities.

Joe came up with a solution.

"I got plenty of free time, Rose. If you want to run the store,

I could work for you three days a week, just like I did for Danny.

Sunday, Tuesday and Wednesday."

My mother nodded, enticed by

the idea of being a boss, stepping into her husband's role. Now,

if I would only cooperate, rearrange my life so I could come in

every Sunday, Monday and Thursday, then she'd try working five days.

"At least I'll be with you,"

she explained. "Who else do I have left?"

I didn't have the heart to

turn her down, and if truth be told, a part of me was beguiled at

the prospect of taking over for my father, actually running his

store. So I agreed to be there three days a week–for a while.

We'd be open Sunday through Thursday. Most of the shops in the area

were run by orthodox Jews, and they were all closed on Saturday.

In a nod toward religious freedom, in the 1930's Mayor LaGuardia

had granted the merchants of Orchard Street a special dispensation

from the city's "Blue Laws" that were in effect at the time, permitting

them to stay open for business on Sundays.

Once the decision was made,

I took a three month leave from my school psychologist job, and

we resumed the inventory with new zeal.

When we announced our intention

to keep Universal Hosiery alive, Moishe, speaking as both

cousin and lawyer, tried to dissuade us. My father owned half of

the abandoned tenement building where the store was housed, and

Moishe thought it was a big mistake not to just sell everything.

"What do you know about running

a retail business?" He asked. "Two women alone. It's crazy."

I resented his lack of faith in me. "We

could try."

He shook his head. "Your father left

enough so your mother never has to work. Besides, you can get a

good price for the property in today's market. Be smart. Take the

money and run."

I explained this wasn't about

money, but about giving my mother a reason to get up in the morning,

to feel useful. He wasn't convinced. "Can't she find something else

to occupy herself with? Let her volunteer in a hospital."

My mother was never a woman

to enjoy hanging out with friends. She couldn't understand the ladies

in her building who played cards or Mah Jongg for hours on end.

"Nahreshkeit," she called it. Foolishness. Keeping a home

for her husband was what filled her days. It may not have made her

happy, but it was what she knew. Now, with him gone, there wasn't

much to do in the house, and shopping held no interest for her.

Nothing held interest for her. My dad was the one who had brought

vitality into our home; it was his curiosity about life, his energy

she'd inhaled for sustenance. He was the one who sang in the shower.

So now, if my mom was actually

expressing a desire to do something, even if it seemed fiscally

unwise, I certainly wasn't going to stand in her way, nor I told

Moishe, should he. Convinced of our determination, if not our wisdom,

he recommended we incorporate to protect us from personal financial

risk. This meant my mother, at the age of seventy-eight–she

told everyone she was seventy-three–became the president of

a corporation. She couldn't resist smiling as she signed the certificate

of incorporation, her short curly hair freshly dyed and varnished

into a honey brown pouf for the occasion. I, too, became a corporate

officer for the first time in my life, listed in the Minutes as

Vice-President and Treasurer. We had new business cards printed

with both our names in the right hand corner, where my father's

used to be.

We chose Christmas Day, 1981,

two months after the death of Daniel Potkorony, proprietor, to reopen

the doors of Universal Hosiery Company, now reincarnated

as Universal Hosiery Corporation. It was a Friday, not one

of the days we ordinarily intended to work, but many Orchard Street

stores stayed open on Christmas hoping to benefit from last minute

gift shoppers. Sunset, the beginning of the Sabbath, would arrive

a little past four, allowing us a chance to begin our tenure as

shopkeepers with a short first work day. The plan was to open at

ten and close around two. We each had our own set of keys. There

were two locks on the entrance door, and three on the heavy metal

security gate in front of the store, an ancient contraption made

of iron that spread and closed like a fan. Since Joe was merely

an employee, and only a relative by marriage, my mother didn't think

he merited the prestige of having his own keys, although there was

no way she could open the gate without his help. As the lone male

in our group, Joe automatically assumed responsibility for operating

the gate, firm in his belief it was not a job for a woman. I, however,

insisted on learning how it worked, and under his reluctant tutelage

managed to succeed in closing it a few times by myself.

The two of them arranged to

meet in front of the store a little before ten. I was driving down

from upper Manhattan, and would try to arrive at the same time.

"Don't be late," my mother

warned. "We got a lot to do."

She looked to me for guidance.

I was counting on Joe. Henry, who had become my retailing mentor,

also promised to stop in. He'd been especially helpful in teaching

me how to price merchandise, offering specific instructions about

discount store profit margins, although it was no secret that price

quotes on Orchard Street were hardly firm. I kept the cost list

handy for reference and wrote the per dozen price on many of the

boxes, hoping customers would be less likely to dispute written

figures. I knew we needed change for the register, and had gotten

a bunch of singles, fives, and tens from the bank. The coin compartments

were already stocked. This was a strictly cash business, no credit

cards, and checks accepted only if you had proper ID and looked

honest. My dad had many regular customers who paid by check, but

Rose was disdainful of my willingness to accept them.

"What do you need it for? You're

just asking for trouble. I say cash only."

The night before our inaugural

business day, I took a chlorotrimeton pill at bedtime, hoping the

antihistamine would make me sleepy. I did fall asleep quickly, but

lurched awake several times during the night, unable to recall the

dreams that were making my pulse race and my heart pound. As morning

drew close, I gave up trying to sleep and decided to drive down

to the store early, to be the first one there, telling myself I

could do some last minute arranging, get everything set before Joe

and my mother arrived. What I really wanted was time alone with

my father, convinced his spirit still hovered around the dust coated

cardboard boxes, the faded black floor tiles, and especially in

his check-book, his old letters. Everything I touched, everything

I smelled, contained molecules of Daniel Potkorony. He was there,

definitely, his presence confirmed by a lingering scent of Taboo,

the pungent aftershave he wore faithfully, and Helmar, the sweet

Turkish cigarettes he chain-smoked. I wanted to rummage through

his desk and run my fingers over words he had written, to try copying

some of those words with his pens.

The weather was clear and sunny

on Friday morning, but the temperature was biting cold, in the single

digits, unusual even for New York. How many people would actually

come shopping in this weather? Part of me wanted a crowd at my door,

yet I was afraid of becoming overwhelmed if too many customers showed

up at once. I hadn't completely memorized where all our merchandise

was. It would take time to find things. My mother would be extra-nervous,

expect me to handle everything at once, then blame me for any mishap.

By the time my car pulled into

Orchard Street, I'd unzipped my ski jacket and removed my gloves,

yet my palms felt sweaty and my throat extremely dry. It's only

pre-performance jitters, I thought, telling myself it would pass

as soon as we made our first sale. I found a parking space right

in front of the store, and took that as a good sign. It was eight-thirty

in the morning, and none of the other shops had opened yet. The

street was empty, unnaturally quiet, like Brigadoon before sunrise,

a movie set awaiting the call to "Action!"

I put my gloves back on to

protect my fingers from freezing, then set about opening the security

gate. I got the locks unbolted easily enough, but the heaviness

of the iron grill proved too much for me. It felt like it was nailed

to the ground. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't move it enough

to access the entrance door. I tugged, heaved, cursed, rested, then

tried again. No luck. That was not a good sign. Just as I was about

to concede defeat, I spied a man across the street, ambling down

the block.

"Yoo hoo," I called. "Hey,

Mister."

"You want me?" the man replied

uncertainly.

"Yes. You. Can you help me?"

Nodding, the man crossed the

street, sauntering towards where I stood. He was a very tall man,

with skin the color of coffee beans, easily over six feet, and way

too skinny for his height. I judged him to be in his thirties, but

I could have been off a decade in either direction. He was dressed

in faded jeans, a black turtleneck sweater and a thin parka jacket,

hardly enough to keep warm on a day like this. If he wasn't an actual

vagrant, he certainly didn't look like a man with a comfortable

residence and steady employment. He smelled faintly of alcohol.

I wondered if he was someone to be afraid of, but decided no. He

had a kind face, intelligent looking eyes, and besides, I was desperate

to get into the store before my mother arrived.

"I can't get this gate open,"

I told him. "It's worth five dollars to me if you can do it."

The man grinned, and I saw

that two of his top front teeth were missing.

"No problem, ma'am. I'll be

happy to." With one hand, he pushed open the gate as easily as if

it were made of cardboard.

"Thanks a lot," I said, opening

my bag to give him the five dollars. I considered the money well

spent.

He shook his head and held

up one hand. "That's okay. I can't take money for doing a lady a

favor. That ain't how my mother raised me."

"Well, I'm grateful." I looked

at him with new eyes. "What's your name?"

"Curtis Hightower."

I held out my hand. "Pleased

to meet you. My name is Sandy."

He barely touched my hand when

he shook it. "Please to meet you, Miss Sandy. I've just come up

from South Carolina, looking for work. You have any jobs need doing?"

"Not at the moment." It made

me uncomfortable being called 'Miss Sandy' like I was some kind

of plantation owner. Still, I wanted to do something for him. "How

about you take the five dollars and buy me coffee with milk and

a buttered roll . . . and get something for yourself."

Curtis took the five dollars.

"Thanks. I'll get myself a cup of hot soup, if it's all right with

you, ma'am." He flashed me his toothless grin and went across the

street to the deli, while I finished opening the store. When he

returned, I told him we could use someone to mop the floor on Monday

if he was interested. He thanked me and left, promising to think

about it. I sat down at my father's desk to eat my breakfast, feeling

rather proud of myself. I'd just had my first experience as a store

owner, encountered an obstacle and handled it successfully. Good

for me.

During the next six months

I felt like Alice, lost in a wonderland that was sad as well as

bewildering. Where was I and how did I get here? On the evenings

before my store days, I'd lie in bed and think things like, "Tomorrow

the store . . . My father died . . . Instead of a father, I have

a store . . . The store has become my father. It gives me money,

it makes me do things . . . And it comes with my mother."

We got used to the stream of

regular customers who inquired after "the man who always was here--you

know, the big guy." They were visibly shocked when they learned

my dad had died. It comforted me to hear their anecdotes, their

own treasured memories, their expressions of admiration, even awe.

"I need a dozen dress nylon

socks in assorted colors," a young man said. "Can you help me?"

"They're on display right behind

you," I replied, proud of my new arrangement. I'd set out two rows

of socks in open black Universal Hosiery boxes decorated

with my Dad's typically modest "Worn The World Over" logo in bright

red. "Just take what you need."

"But your father always told

me what colors I needed. He never let me choose. I counted on him

to know what was right for me."

The same kind of thing happened

with requests for underwear, a phenomenon I labeled "Customer Anxiety,"

something never mentioned in my psychology texts. I was torn between

feigning expertise and encouraging autonomy. My father was a benevolent

despot, and his subjects had been content with his rule, but it

was not a role I took to easily. It felt more natural to wait calmly

for irresolute shoppers to obsess over whether to buy the blue socks

or the brown, then offer support for their decision. My mother,

however, had no qualms about interrupting such slow dealings, sometimes

going as far as pulling socks right out of a person's hand.

"We don't have all day," she

would scold, as much to me as to the intimidated patron. "Come back

when you make up your mind."

I was mortified, but customers

seemed to take her rudeness in stride. It's easier to put up with

abuse from a feisty old lady who isn't your own mother.

Noting my distress, some of

them would try to console me. "Don't worry about it," they'd say,

especially the men, who seemed to find my mother cute. But it was

hard for me to ignore her behavior. She was undermining my position,

treating me as a wayward child. I tried instituting a rule that

neither of us should interfere when the other one was in the middle

of waiting on a customer.

"I'll do it my way, Mom. and

you do it yours."

"But you do it wrong. I can't

stand to watch you."

"Then don't watch."

And so it went. We'd squabble

between sales. As I became more familiar with the merchandise, I

found myself supervising her exchanges with shoppers.

"We don't have any flannel

shirts" she would say, if she couldn't remember where they were.

"But we do, Mom. In the storage

room. I'll get them."

She'd purse her lips, frown

and say something like, "We just got in a new shipment. My daughter

didn't tell me what came in."

A more serious battle involved

plumbing. The only source of heat in this six-by eighty-foot space

was an ancient gas blower that hung from a ceiling pipe and blasted

hot air toward the front of the store. Once upon a time it might

have had a working thermostat, but now, the only way to stop the

fierce gusts was to turn the switch off manually. It was so cold

without the blower you could see your breath, yet after ten minutes

with it on, the entire front section became impossibly hot. My mother

liked the intense dry heat, and wanted to keep the blower on all

the time, but when I began to perspire I'd turn it off, only to

have my mother or Joe flip it on a few minutes later. "It's like

a sauna here," I'd mutter. All day long we'd alternate between roasting

and freezing. There was also no hot water. And worst of all, we

had no bathroom! My father had apparently never thought it necessary

to install one. There was a cold water sink in the back, which according

to my uncle Joe, was toilet enough for the men.

"A lot of stores on the block

don't have toilets," he told me on our first day of inventory taking.

I found that hard to believe.

"So what do you do when you have to go?"

He gestured toward the sink.

"That's not going to work

for me," I said, then turned to my mother. "You can't expect me

to go in the sink."

"Use the toilet in the coffee

shop on Grand Street," she said. "That's what I always did."

"But that's two blocks away."

"So what. So you walk a little."

"I don't want to have to put

on my coat and leave every time I need to pee. That's crazy."

The next day my mother brought

in an old pot. "We'll keep this in the storage room. Nobody will

see you. When you're done, just empty it in the sink."

For the time being, I used

the coffee shop's facilities, but when we decided to run the store

ourselves, I pressed for a bathroom.

My mother resisted. She didn't

want to change anything.

"If it was good enough for

Daddy, it's good enough for me."

"Daddy didn't menstruate,"

I reminded her. "I'm not going to work here without a toilet. I

also need hot water to wash my hands."

"Fancy lady. Big shot. Go 'head,

waste money on nonsense. You don't even know how long we'll keep

the store."

She argued, she insulted, but

I remained adamant. No toilet, no work. Finally she capitulated.

"Do what you want. You never

listen to me anyway."

She sulked for days, finally

extracting my promise not to install it in her presence. "They'll

make such a mess. Daddy's whole store will be ruined. Then you'll

be sorry."

I was in my mid-forties, way

too old to be admonished like that. I just didn't know how to stop

her–or how to stop myself from feeling guilty about wanting

to make life easier. One thing I did know though, from years of

practice, was how to do things behind her back. On a Friday in January

when the store was closed, Joel the plumber, installed a small water

heater in the basement, and a flush toilet in a narrow crawl space

my father had used as a storage closet.

I reveled in the luxury of

a flush toilet right on the premises, not to mention a sink that

offered hot water. My hands had become badly chapped from handling

dusty boxes and cartons with nothing but frigid water to wash them

in. If my mother appreciated the changes, she kept it to herself.

Still bruised at being overruled, she spent the next few weeks evaluating

how frequently I used the bathroom.

"Again, you're going?" she

would ask sarcastically, as if overuse was detrimental to the toilet.

"Do you go so much at home, too?"

I refused to join that battle,

and the comments eventually abated along with my mother's reluctance

to use the facility herself. Instead, she became the bathroom overseer,

the supreme judge over who was permitted use of it. Occasionally

a customer, in dire need, would request permission, which my mother

would deny.

"No. We don't have one," she'd

say curtly. "Go to the coffee shop."

After the

customer had gone, she'd lecture me, and Joe too if he was there,

about how important it was not to "let in any strangers." Neither

of us dared oppose her to her face, but once in a while I made an

exception if my mother wasn't around.

These first months I struggled

to learn everything about running a business. Immersed in the details

of where to buy and display merchandise, how to set prices and become

facile at selling, I dream-walked through my changed life. Each

day I'd suffer intermittent attacks of grief, sudden punches in

the gut powerful enough to make my throat swell, my eyes tear. I

missed my father terribly. Responsibility for my mother was burdensome,

yet without the familiarity of her predictable behavior to cling

to, I would have been at a loss for breath. Immersed in consoling

her, in battling her, I was momentarily distracted from mourning.

The same was probably true for her. Any emotion other than anguish

was a welcome respite.

January through March were

traditionally slow business periods along Orchard Street. Christmas

was over, Easter and Passover not yet here. On the Mondays and Thursdays

I spent in the store alone with my mom, if the weather was bad,

hours might pass without a single customer. We'd busy ourselves

straightening and arranging stock, drink coffee, reminisce and argue.

She insisted on continuing to bring lunch for the two of us despite

my plea for her to stop.

"But I like bringing you food.

I used to make Daddy sandwiches. He didn't complain."

"I don't mean to complain.

It's just that I'm tired of cream cheese and jelly. The same thing

every day gets boring. I'd like something else for a change."

"So I'll make something else,

if you're that fussy. How come I don't get bored eating the same

food?"

My mother never actually got

hungry. If she experienced food as a source of pleasure, she hid

it well. As far as I could tell, she ate because eating was necessary

to stay alive. My father was the one who maintained a love affair

with his palate. Anything that triggered memories of dishes enjoyed

in the past could make his voice grow soft and his eyes dreamy.

Grossinger's corned beef was forever enshrined in his food hall

of fame, as were Ratner's onion rolls. He never tired of reciting

in minute detail the blissful taste of a particular food eaten months–sometimes

years–ago, offering these unsolicited recollections in contrast

to whatever my mother had just served him.

"This potroast is hard. It's

got no taste. Aach!" He'd try another bite and sigh. "No taste whatsoever."

"What's wrong with it?"

"You didn't cook it long enough,

that's what's wrong." He'd turn to me. "My mother–your Bubby–she

knew how to make a potroast..." He'd lick his lips. "So soft, it

would melt in your mouth."

My mother would inevitably

frown, directing her reply to me as if he weren't there.

"Your Bubby's potroast was

like shoe leather. He doesn't remember."

I hated being put in the middle

of their quarrels. I didn't even like "potroast," which my family

always pronounced as one word, as if were the name of an animal

rather than a way of cooking.

Business picked up during April

as the weather grew warmer and the days longer. The crowds on Sunday

were exciting. Once I learned the merchandise and could locate things

quickly, the store became a home–my home, as if I'd been born

there. I would become energized by the steady flow of people asking

for things. From ten in the morning to five in the evening, sometimes

without a break, I jumped around, running up and down the aisle

from the front of the store to the back then to the front again,

over and over. I never got impatient with customers. They were more

than potential sales. They were my clients. Servicing them was therapeutic

to us both. As a psychotherapist, if I was lucky after six months

of treatment a client would get a little better, hopefully no worse.

Progress was slow. But as a shopkeeper, if a man walked in asking

for a dozen black socks, I could give him what he needed immediately.

"Great," he'd say. "How much?" I'd tell him the price, he'd hand

me the money, and I'd give him the socks. Instant gratification.

I'd made him happy, and I had some hard currency to put into the

register. Green money has a lot more magic than a check.

At the end of a busy Sunday,

I'd have at least one, and sometimes two thousand dollars to count.

I'd write out the deposit feeling very rich. It didn't matter that

most of the money wasn't profit. It was cash, more than I'd ever

handled at one time. I loved the feel of it, the smell of it, building

neat piles of tens and twenties all facing in the same direction.

I delighted in the fifty dollar bills and the occasional hundred,

counting and recounting.

For fear of theft, we didn't

want to keep a lot of money in the cash register during the day,

so my mother and I would periodically empty the large bill compartments,

stashing our hoard in an empty sock box behind the counter. I'd

finger the bills greedily, watching the pile grow. Rose would have

loved to be in charge of money, but she didn't have my speed and

skill, nor was she knowledgeable about bank deposits. We compromised.

I'd count and tally the bills, hand out our "weekly pay" and prepare

the deposit slip. She'd take the deposit to the bank the following

day. Every Sunday I'd give the same prearranged amount to Joe, my

mother, and myself. Our Salaries. If the total for the day was particularly

large, I'd take a little extra, telling myself that as boss, it

was my right. Of course I didn't tell my mother that, but then again,

she was also free to take what she wanted. If she ever did so on

the days I wasn't there, she never told me. For fear of theft, we didn't

want to keep a lot of money in the cash register during the day,

so my mother and I would periodically empty the large bill compartments,

stashing our hoard in an empty sock box behind the counter. I'd

finger the bills greedily, watching the pile grow. Rose would have

loved to be in charge of money, but she didn't have my speed and

skill, nor was she knowledgeable about bank deposits. We compromised.

I'd count and tally the bills, hand out our "weekly pay" and prepare

the deposit slip. She'd take the deposit to the bank the following

day. Every Sunday I'd give the same prearranged amount to Joe, my

mother, and myself. Our Salaries. If the total for the day was particularly

large, I'd take a little extra, telling myself that as boss, it

was my right. Of course I didn't tell my mother that, but then again,

she was also free to take what she wanted. If she ever did so on

the days I wasn't there, she never told me.

I'd feel wired by the time

we closed, and usually arranged to have dinner out with friends

afterwards, often choosing expensive restaurants and picking up

the check for everyone as my father used to do, flushed and excited

as I paid with green money.

The leave of absence from my

school job ended in April. Now, in addition to the three days in

the store, I resumed working Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Fridays as

a School Psychologist. That meant a six day work week. On Saturday,

my one day off, I'd collapse and spend much of the day in bed feeling

sorry for myself, convinced I'd been struck by lightning and left

to suffer the aftermath of the burn alone. I had a lot of money,

along with a lot of new responsibilities and no father. My youth

was gone, I had no lover, and the future looked bleak. I was aging

rapidly and if my father had died, then so would I.

My friends commiserated. Carol

suggested I visit a psychic.

"Marianna is great," she gushed.

"Absolutely gifted."

"More gifted than a licensed

psychologist?" I'd been toying with the idea of seeing a therapist,

but when you're a psychologist yourself, it's hard to find anybody

as wise as you think you are.

"It's different, much faster.

Marianna will know immediately how to help you. She'll tell you

what to do, not wait for you to guess. Try her, what have you got

to lose?"

Seventy-five dollars, I thought.

At one time that would have been a prime consideration. Before my

dad died, I functioned on a very tight budget. The cost of the Sunday

Times was almost the same as the cost of a small box of spaghetti

and salad fixings. I didn't always have the ready cash for both.

Now, with my father's legacy of the store and half a building, not

to mention an extensive portfolio of stocks, bonds and cash, it

seemed to be raining money. A warm rain can refresh, but a cold

rain can make you sick. My inheritance did both. I no longer had

to worry about money, but I had to accept that the windfall was

tied to the loss of my father.

I scheduled an appointment

to see Marianna, waiting three weeks for an opening in her apparently

very busy schedule, and then accepting 8:00AM on a Saturday morning,

much earlier than I wanted, but all she could offer. Marianna lived

on the ground floor of a shabbily kept building in Greenwich Village.

I almost cancelled, but forced myself to go. "This is me doing something

for myself," I murmured over and over. "Just for me."

Marianna was a large woman,

close to six feet tall with a husky build. She wore a long sleeved

flowered caftan, several gold necklaces, and at least a half dozen

bracelets. Her features were mannish, and she had a deep voice.

It occurred to me she might be a male transvestite. But wouldn't

Carol have told me that? Unless she thought I wouldn't go under

those circumstances. Well, I was here, might as well make the best

of it. A tape of the session was included in the fee, and after

a few pleasantries, Marianna inserted the cassette.

"Shall we begin?"

I nodded and waited.

"Please give me something of

yours to hold, like a watch or a ring. It helps me pick up your

spiritual scent."

Rather skeptically, I handed

her my watch, an inexpensive Timex I'd had for years and wore constantly,

even to sleep. She clasped it in both hands and sat silently for

a few minutes with her eyes closed before asking "What would you

like to know?"

"My life's changed dramatically

in the last few months." I didn't want to reveal too much. "Can

you tell me about the future? Or maybe suggest some good ways to

handle the present?"

"I can" she said, and proceeded

to describe my turmoil and sadness so accurately, I could have sworn

Carol had clued her. Tears came to my eyes as she talked about my

childlike charm, a quality I particularly liked, now irretrievably

shattered. I didn't want to be reminded of that.

"You've suffered a great loss."

Another news bulletin I didn't

need to hear again.

"I've recently lost my father.

Can you tell me something about what lies ahead?"

She rubbed the watch between

her hands. "I see money," she began.

I interrupted. "Well he did

leave my mother and me some money."

"This is different from an

inheritance. I see money hidden in a box. Some kind of old box.

I can't tell if it's metal, but there's definitely money in it.

A lot."

The word "box" reminded me

of the store, and I told her a bit about my new life. It felt good

unburdening myself and she was a sympathetic listener.

"You've really had a rough

time," she said, and turned the tape over to the other side.

"I'm sensing money somewhere

in your father's house or maybe in his shop."

I sighed. Money was the least

of my needs at the moment. Nevertheless, the idea of finding more

was seductive. I resolved to brave my mother's scorn and talk to

her about Marianna's prediction. You never could tell.

The next day in the store,

over morning coffee, I regaled Joe and my mom with the details of

my session with a psychic, omitting the part about its occurrence

on the Sabbath. I tried to present the whole experience lightly,

a lark, making sure to credit Carol as the instigator. After recounting

Marianna's predictions I asked, "So, what do you think?"

My mother responded with her

usual "it's nonsense" shrug and grimace combo, yet apparently something

about the possibility of finding money intrigued her. "What about

you? Do you believe that?"

"I don't know. It's possible.

Some of the things she said about me were true. Maybe this'll come

true also."

"Was the lady a gypsy?"

In my mom's experience, only

gypsies told fortunes.

"I don't think so." I didn't

want to tell her I wasn't sure Marianna was even a lady.

"A guy I worked with at the

Post Office used to visit a fortune teller," Joe chimed in. "He

said her advice saved his life."

"I don't believe in it," my

mother concluded. "It's throwing away money. How much did you pay

this gypsy?" "What's the difference?" I

could say five dollars, and it would still be too much in my mother's

eyes. "Besides, she's not a gypsy." I turned to Joe. As far as you

know, did my father ever leave large amounts of money hidden in

the store?"

Joe flicked his cigarette ash

into a saucer my mom had placed on the counter for this purpose,

glancing at her for approval. "He didn't used to talk about such

things with me, you know."

We knew. Joe had only been

summoned to help out in the store after my uncle Morris died. Morris

was the blood relative, Joe was a poor brother-in-law who had not

provided very well for his family. He was an appendage, not an equal.

"But," I persisted, "did you

ever see anything?"

"A few times I saw him take

a package of bills and give it to your mother's cousin."

"Which cousin?" My mother was

definitely interested now.

"You know, the lawyer. What's

his name?"

"Moishe?" I prompted. The one

who's helping us with the estate?"

"Yeah. That's the one. Now

and then Dan would give him money, and a few weeks later, Moishe

would bring it back."

I made up my mind to ask Moishe

about this. Funny he'd never mentioned it.

"How about at home, Ma? Did

Daddy ever hide money at home?"

"Not that I saw, but you know

your father. Did he ever tell me anything?"

"Well," I said. "From now on,

let's keep our eyes open."

And we did, Rose, more persistently

than the rest of us. She had found a task that engrossed her, something

to fill her time. If her husband had secreted cash anywhere, she

was determined to find it. For three months she searched in vain.

So did I, but I tried to be less obvious about it. The storage room,

the merchandise shelves, behind the counter, in the heavy iron safe

upon which the register sat, the obvious places, the least likely

places, we rummaged through everything. Nothing turned up. At home,

my mother explored every inch of the apartment without success.

After a while my interest flagged and we gave up. At least I did.

When I telephoned Moishe to

question him, he admitted to having done money lending deals with

my dad. "Once in a while one of my clients might need a few thousand

dollars short term, and prefer not to go through a bank," he explained.

"Dan--your father--always seemed to have a supply of cash on hand.

He made good interest on his money, and I got to help out some clients."

"Was this legal?" I wanted

to know. And how much money are you talking about?"

"Perfectly legal," was his

reply. "Anywhere from five to twenty thousand."

"If there's nothing wrong with

this, how come you didn't tell me about it?"

"There'd be only two reasons

to tell you," Moishe answered, using a sing-song voice, as if he

was reciting from the Talmud. "The first reason would be if there

was money outstanding, and there wasn't. The second, and only other

reason to mention it would be if you had an interest in lending

spare cash. Do you?"

"Maybe." While there may have

been nothing illegal about lending money, I wondered whether my

dad had reported the income from these loans to the IRS.

Two months after we took over

the store, Curtis Hightower, my opening day hero, reappeared one

Monday morning, wearing the same flimsy parka, which now sported

a rip at the shoulder and a broken zipper. He stood in the doorway

and whispered in a barely audible voice about my offer to pay him

for mopping our floor, reminding me I had specified Monday, and

apologizing for taking so many Mondays to show up.

My mother came over, eyed Curtis

suspiciously, then as if he weren't there, asked in Yiddish, "Vas

villt ehr?" What does he want?

"Curtis, this is my mother,

Rose Potkorony," I said, embarrassed by her rudeness."

"Pleased to meetcha, Miss Rose."

He bowed his head in her direction. She barely nodded.

"Curtis is going to wash our

floor and maybe wax the linoleum, if you think it's a good idea."

"For how much?" my mother asked

him.

"Would ten dollars be all

right?"

"Fine, I said, before my mother

could begin to haggle.

"Maybe he could also dust on

the top shelves," she said, taking in his height.

"Whatever you say, Miss Rose."

My mother, somewhat assuaged

by Curtis's willingness to please, as well as his deference toward

her, marched him over to where the cleaning supplies were kept.

When he was done, I handed

him the agreed upon ten dollars, plus an extra five while my mother

wasn't looking. I also gave him a black thermal shirt, which she

did see.

"It's freezing outside," I

explained. We don't only have to give charity to yeshivas, you know."

She didn't reply. Curtis had

carefully washed, rinsed and waxed our long narrow floor space until

the black marbleized rubber tiles glistened. We agreed it would

be good if he could come in every Monday to do the floor and other

odd jobs that might come up. My mother decided to have Curtis take

all the old boxes of receipts down from the shelves in the storage

room for her. It was one place she hadn't yet examined in her ongoing

quest to find the cash windfall predicted by "The Gypsy," as Rose

persisted in calling Marianna.

So, Curtis became a regular

employee of Universal Hosiery Corp. Maybe "regular" is too

strong a word. Sometimes he would show up at the appointed time,

sometimes not. Once he sent an emaciated looking Latino man to inform

us, "Curtis ain't coming in today. Said to tell you he's sick."

Alcohol fumes lingered in the air long after the messenger left.

We knew Curtis also drank, but no matter what he did when he wasn't

in our store, he always reported for work sober. I wondered how

much his fear of my mother influenced his effort at sobriety.

On the days Joe and Rose worked

the store by themselves, I was required to call and check in at

least once. If I didn't, my mother would invariably seek me out

at my school psychologist job. It was disconcerting, but I was benevolent

about it. No matter if the questions were trivial, and they usually

were, I felt it behooved me as a daughter to be available to my

mother. As Universal Hosiery's Chief Executive, it also made me

feel important.

"Did you tell the Window Dresser

to come in?" my mother asked one day. She was asking, but her voice

was accusing.

"No," I replied defensively.

Even if I had, I might have hesitated admitting it, reluctant to

engage in the inevitable battle over innovation, over change of

any kind.

"Well, he said you told him

to."

She was referring to Irwin

Goldstein, Orchard Street's prime Window Dresser. A short, slender

man in his fifties with a wide smile and a prominent "Adams Apple",

he looked like an aged jockey and seemed always to be in very good

humor, which struck me as strange, considering he made his living

squeezing into narrow storefront window spaces and stapling dry

goods samples to pieces of oak tag.

Daniel Potkorony

was one of the few proprietors who hadn't used Irwin's services,

preferring to do the job himself, no mean feat for someone my father's

size. Our window space was four feet square, six feet high, and

accessible only through a tiny opening no broader than twenty inches.

Dressing the window meant first pushing aside the rolltop desk that

blocked this opening, then crawling through it sideways. Once inside,

my dad would unpin the rows of socks, underwear, and pajamas neatly

tacked to sloping pieces of sheet rock, and replace them with a

similarly displayed sampling of fresh merchandise. Hand-lettered

signs identified styles, and notified potential customers of the

"unlimited selection inside." Since neither inventory nor signs

ever varied, the main purpose of redoing the window twice a year

was to replace sun-faded merchandise, or in my father's words, to

"make the window look fresh."

As Irwin worked his way through

the Orchard Street establishment windows, he undoubtedly noticed

the increasingly faded and dusty state of our little showcase, but

he'd waited until April before coming in and introducing himself

to me. My mom was helping a customer in the back and didn't get

to meet him that day.

"I knew your father well,"

he said, leaning against our door. "I just stopped in to tell you

I'm sorry he's gone."

Irwin went on to recount how

he never could convince my Dad to let him do any work for Universal.

"He wanted to do everything himself. I used to kibbitz him about

how he was taking away my living. He was a great guy, Danny was."

I nodded. As Irwin turned to

leave he said, "You should really think about fixing up your window.

Summer's coming. I could clean out the space for you, put in a new

paper backdrop. It would look much nicer, and be good for business

too."

He was probably right, but

I wasn't ready to have my father's last display dismantled just

yet. "How much would you charge?" I asked.

"My standard rate for a job

like yours is a hundred and fifty."

"I'll let you know. If not

now, maybe for Christmas."

"Whatever you say." Irwin took

out a business card. "Call me any time. If I'm in your neighborhood,

I'll stop by to say hello, just like I used to do with Dan."

When my mom heard about Irwin

and his offer she immediately went to take a closer look at what

little she could see of our window from the inside of the store.

She too, wanted to extend the life of whatever my father had touched,

but had a hard time justifying the preservation of dirt anywhere,

for any reason.

Behind the display of merchandise

were a dozen empty sock boxes, neatly stacked in three rows, and

covered with at least an inch thick coating of dust. It looked like

they'd been put there years ago to help keep the sheet rock in place.

My mother immediately vowed to clean every one of these boxes, and

tried to press me into crawling far enough into the opening to reach

them.

"Forget it" I said, repelled

by the accumulation of dust. "Let it stay the way it is for now.

We'll clean everything when we get the window dressed."

"I'm just gonna wipe each box

with a damp rag," she replied as if she hadn't heard me say no.

"It won't interfere with the display. Why should we have dust?"

I shook my head. "When you're

ready to do the whole job, I'll call that window dresser man, Irwin.

For now, let's just leave it."

She pouted. "I'll do it myself.

Joe will help me."

"Do what you want."

Joe helped by moving the desk

for her one day when I wasn't there, enabling her to poke a feather

duster attached to a foot long pole around the boxes and wipe some

of the dirt away. It wasn't really satisfactory, but the only alternative,

emptying the entire window was still out of the question. We needed

more time.

Occasionally Irwin and I would

pass on the street and he'd greet me warmly. "Don't forget about

the window," he'd say, and I would nod and smile.

"One of these days," I'd tell

him.

So now, my mother was calling

to tell me Irwin had come by again.

"He's having a special," she

reported. "He'll do the whole job for a hundred and fifteen dollars."

"Do you want to do it?" I asked,

relieved when she said no.

"It's too much trouble. I

don't have the strength."

"We don't have to do it just

because he tells us to. Tell him I'll call him when we're ready."

For once

my mother and I agreed. After we said goodbye, I sat quietly, waiting

for images of the store to fade so I could become a functioning

school psychologist again.

December, 1982, our second

Christmas in the store, found us knee deep in customers.

Shoppers who preferred no-nonsense direction

sought out my mother.

"Can you help me? I want to

buy ladies pantyhose as gifts," a portly middle aged man approached

her, holding a slip of paper with several styles and sizes noted

on it. Rose picked out the items and convinced him to take a full

box in each style.

"Three pair in a box. We give

you low prices, but you have to take a full box."

That was not true, but he didn't

know it and nodded his acquiescence. He agreed to buy four boxes,

a good sale. As she began to figure the cost, the man looked down

and checked his list.

"Oh, by the way," he said.

"Do you have any crotchless panty hose?"

My mother was nonplused. "What's

that?"

He repeated, "Crotchless panty

hose."

She held up one hand. "Just

a minute" she said, and walked closer to me. "Do we have crotchless

panty hose?" she whispered. "What is that?"

I smiled and explained. "It's

panty hose with the crotch missing. We don't carry that kind."

She still looked confused,

but returned to the customer. "In this store we sell you the whole

thing. Later you can cut out the parts you don't like."

Irwin, the window-dresser,

stopped in at the end of January to inquire whether we thought Universal

Hosiery's shabby display had negatively affected our Christmas

selling. My Mom and I looked at each other, then she sighed in a

way that acknowledged Irwin might be right. It was time to let go

of my father's final exhibit, now grown so dingy it no longer honored

his memory.

"Maybe we should wait until

spring," my mother tried to procrastinate one more time. "Then we

could include summer merchandise."

"On the other hand, it might

be better to do it now when business is slow," I responded.

After Irwin reassured us we'd have

room for samples of all our merchandise and offered us his off-season

discount, we succumbed and set a date for late morning, the following

Thursday. This would give me, my mother, and Curtis time to take

the old display down and clean the space in preparation for Irwin's

professional efforts, installing backdrop paper, positioning samples,

and stapling the new stock in place.

"Pins are passe`," he informed

us. "No one uses them anymore." Then, noticing my mother's disturbed

expression, he offered a conciliatory amendment. "Except maybe in

a few places, like pinning a description to a pajama or a shirt.

That would be okay. You can even use some of Dan's old signs. But

everything else gets stapled."

In addition to selecting which

merchandise should go into the window, we were given the chore of

doing all the prep work. An arduous job. I confess one of the reasons

behind my acquiescence to this project was that I'd scheduled a

short vacation trip to California beginning the next day. I planned

to spend a few days with Eugene, who was living in Berkeley, then

drive to Los Angeles to consult with a psychologist at UCLA who

had done research in the area of my own dissertation study. I was

now up to the gathering of data stage, and looked forward to professional

feedback. Assigning my mother the task of dealing with the discarded

window merchandise, not to mention overseeing the removal, at last,

of the stack of old dirty sock boxes, would keep her occupied and

assuage some of my angst at leaving her alone.

Curtis met me as arranged in

front of the store at 8:30 Thursday morning. I'd promised him twenty-five

dollars to work the day as our window-dressing assistant. He moved

the rolltop desk just enough to give me a clear, albeit small path

into our diminutive glass showcase. My mother arrived, and after

the three of us fortified ourselves with coffee and cake we set

to work. I crawled into the window space and began by passing the

dusty sock boxes to Curtis. They bore the "Worn The World Over"

Universal logo, and aside from the heavy layers of dirt, they looked

pretty intact. My mother decided that if we cleaned them they might

be useful to replace some of our current display boxes that had

become worn and cracked.

"Please don't bother about

boxes now," I pleaded from inside the window, where with unexpected

trepidation, I started dismantling the rows of socks my father had

personally pinned to the plaster boards. "We've got too much else

to do. Ask Curtis, to store everything in the back room for now.

You can deal with them next week, Mom, while I'm gone."

Reluctantly, she agreed, and

turned her attention to the piles of faded merchandise I began handing

out to her. She directed Curtis to put socks in one carton, underwear

in another, shirts, pajamas and other miscellaneous items in a third.

"A lot of this stuff is still

good," she announced, adjusting her glasses to get a better look.

"I can wipe off the dust with a damp rag and put it back in stock,

especially the shirts and underwear in cellophane packages. The

rest we'll give to a rummage sale, or keep ourselves."

"Fine, Mom," I agreed. "You're

in charge. Do what you want. All I ask is that you wait till next

week. Right now everything we don't need goes to the back. Okay?"

The next morning I flew to

San Fransisco. Eugene had gotten me a hotel room in Berkeley, near

his living quarters. We'd seen each other over Christmas, which

wasn't that long ago in Eugene's opinion, but we chose this time

for a visit because he was on school break. From my point of view,

it was never too soon to see my son again. I phoned my mother from

the airport, in order to reach her before the Sabbath, what with

the three hour time difference. My mom wouldn't answer the phone

from Friday sundown until Saturday evening. She sounded lonely,

and tired from the effort of the day before.

"Take it easy this Sunday,"

I advised. "It shouldn't be too busy. I'll call you again in a few

days." I made her write down my hotel number in case of emergncy.

On Monday, Eugene and I toured

Alcatraz, and I had the dubious pleasure of being locked in one

of the cells for an interminable five minutes. He dropped me off

at the hotel for a nap before dinner, and I had just lain down when

the phone rang.

"Sandy! Are you there," my

mother shouted into the phone.

Oh, no, I groaned inwardly. What

new calamity. "I'm here. Is anything wrong?" I prayed nothing was

wrong.

"Nothing's wrong." She sounded

excited.

"What is it then?"

"You'll never guess." My mother

actually giggled.

It was not like Rose to play

games. I didn't know what to make of it. "If I'll never guess, then

just tell me. What's going on?"

There was a pause, and I began

to get alarmed. "What, Ma? Tell me."

"Remember the boxes in the

window. The dirty ones you wanted me to throw out?"

"Yeah." I didn't really care

what she did with them, but wasn't going to argue. "So?"

"So, when I was cleaning them

with a damp cloth, I opened them to clean inside, and guess what?"

Without waiting for my reply she continued. "I found money in one

of the boxes, Sandra. A lot of money!"

Wow! God bless Marianna, I

thought. Her prediction had proven true. "How much money?"

"I took the box home in a plastic

bag to count here by myself. I didn't want Joe should know."

"So how much?"

"I just finished counting it

now. There's a hundred-twenty dollars in checks, and close to $23,000

in cash!" My mother was definitely giggling again.

I didn't know what to say.

"Are you sure?"

"Don't you think I know how

to count money?"

"What's the date on the checks?"

"Just a second." I heard papers

rustling. "October 19, 1981. What do you think it's from?"

I thought for a minute. "The

checks and some of the cash are probably receipts Daddy never got

a chance to deposit. The rest might either be money he was going

to lend or had just gotten back with interest. We'll never know.

What's the difference?"

"No difference. I was just

curious." My mom sounded so alive, so triumphant. "Looks like your

gypsy was right."

"I guess so. What do you want

to do with the money?"

"We'll talk about it when you

get home. In the meantime I'll keep it here in my bedroom." Her

voice dropped to a conspiratorial whisper. "I don't want to say

too much on the telephone. I don't think you should even tell Eugene."

I doubted anyone had learned

of our windfall and bugged my mother's phone. "Okay, Mom. This certainly

is good news. We'll talk more about it when I get home."

I did tell Eugene. "That's

amazing!" he said, his voice full of excitement as he began speaking

rapidly. "You should go back to this lady. The next time I come

to New York, I want to go. Do you mind if I tell Dad? Maybe she

could help him find money."

It was sweet the way Eugene

wanted to help his father, but I doubted my ex-husband had any money

he didn't know about. Allan was constantly in debt, and the news

of our good fortune might make him feel envious. "Better not say

anything for now."

We celebrated in a fancy Chinese

restaurant in downtown San Fransisco. The next day I bought him

a stereo for his room, an Olympus automatic zoom camera for myself,

and a new late model Walkman for Nancy. Thank you Daddy.

I returned home late Saturday

night. Sunday morning, before going to the store, I stopped off

at my mother's apartment, so I could look at the cash for myself.

Rose was extremely proud of her discovery. Her detective work had

paid off--big-time. She took me into her bedroom, and ceremoniously

fetched a hat-box from the closet removing the top carefully, then

extricating a towel wrapped package. Gingerly, she unwrapped the

towel which covered a plastic bag housing the now famous sock box.

Inside, I found two envelopes. One envelope contained twenty thousand

dollars neatly organized in packs of ten one-hundred dollar bills

stapled together in the left-hand corner. The second envelope housed

the checks and the remaining twenty-eight hundred dollars in assorted

bills of different denominations.

I caressed the bills lovingly.

"Let's split the twenty-eight hundred and hold on to the rest."

I told her about the presents I'd bought for Eugene and Nancy.

"Buy yourself a gift," I urged.

"Treat yourself to something you might otherwise hesitate to spend

a lot of money on." I pushed bunches of bills toward her. "Go ahead."

My mother sighed. "It's too

late for me."

"What do you mean?"

"Years ago when I wanted to

spend money, to buy nice things, your Daddy never gave me enough.

Fifty dollars a week for the table, that was it. I had to beg for

anything else."

"So now's your chance, Mom.

Buy a fur coat, jewelry, whatever you want."

"It's too late," she repeated.

There's a time for everything. When I had desire, I didn't have

money. Now that I have the money, I don't have the desire." She

smoothed and straightened several of the bills, sighing.

"Well, I'm taking fourteen

hundred," I announced, fearful she would impose her lack of desire

on me. "You can do what you want, but I think you should take it

too. How about a new television set? Or maybe a new air conditioner?

Or both?"

"I'll see."

We opened a safe deposit box

to house the twenty-thousand, and decided to discard the checks.

It was too late to deposit them without arousing suspicion, and

we could certainly afford to relinquish the $120.

The more I thought about it, the more

clear it became that finding the money was a sign my father wanted

me to have his store. That it was my mother who found the money

was as irrelevant as the fact it was she who had always done the

cleaning and cooking. The way I saw it, my father wanted Universal

Hosiery to go on and approved of my running it. And so it was

settled. The store would continue.

|