A

Letter to my Father on the Eleventh Anniversary of his Death

by Stephanie

Hart

A journey into her past reveals the present.

![]()

"For

you Dad, fact and desire often intermingled."

Dear Dad,

You visited my dream last night looking dapper in a navy blue suit with shiny, brass buttons. I wondered at the ease of your gestures as you helped two young women in chiffon dresses into a taxi. Your thick, dark hair moved gently in the autumn wind. The smile on your face was jaunty, confident, and almost ebullient. You were not the man I had known.

Today,

I conjure you up through photographs. I discover you at age six in a black

sailor's suit, red and black striped socks and high-button shoes. You

are standing on the cushion of a tall wooden chair looking proper and

prominent. Your right arm falls easily at your side while your left, bent

at the elbow, rests gently against the spokes of the chair; in your small

left hand you are holding a wilted bouquet of roses. Your hair has been

sculpted into the shape of a cap. Your cheeks appear full and achingly

soft. Your lips are parted slightly. There is a far away look in your

dark eyes as if the physical reality of the moment were inconsequential

to you. I feel your thoughts waft into dreams of imagined greatness, a

journey you will make again and again over the next three-quarters of

a century.

Today,

I conjure you up through photographs. I discover you at age six in a black

sailor's suit, red and black striped socks and high-button shoes. You

are standing on the cushion of a tall wooden chair looking proper and

prominent. Your right arm falls easily at your side while your left, bent

at the elbow, rests gently against the spokes of the chair; in your small

left hand you are holding a wilted bouquet of roses. Your hair has been

sculpted into the shape of a cap. Your cheeks appear full and achingly

soft. Your lips are parted slightly. There is a far away look in your

dark eyes as if the physical reality of the moment were inconsequential

to you. I feel your thoughts waft into dreams of imagined greatness, a

journey you will make again and again over the next three-quarters of

a century.

For you Dad, fact and desire often intermingled. You told me you were born on Staten Island; my birth certificate reveals it was Russia. With the help of your relatives, I reconstructed your early life. You were born in Odessa in the spring of 1904. This picture was taken in 1911, only a year before both you and your father, a builder of patrician stock and sensibilities, crossed an ocean to take refuge in the lap of America from the Russian pogroms. I can envision you on that journey standing on the planks of the ship, your chin pitched upwards, a dauntless little admiral doing battle with the waves.

Once on land, your father's status spared you both the trials of Ellis Island; however, like other Russian Jewish immigrants, you headed directly for the airless tenements of Manhattan's Lower East Side. Your flamboyant redheaded mother and dark-haired taciturn sister soon joined you. A year later the four of you found sanctuary on Staten Island where your father made a respectable living constructing and renting multiple dwellings. Four years later your brother Phil was born, a stocky pragmatist, who worshipped his big brother. You loved him too for his devout simplicity. He seemed to lack the infrastructure of dreams that formed your ambition. You wanted to distinguish yourself from your silent father and effusive mother who let loose a witty hodgepodge of talk in Yiddish and broken English. You wanted to escape the haunted landscape of your sister's face. Like Gatsby you would use the hot clay of desire to reshape your history.

At twenty, after two rejections, the doors of Harvard University swung open. It was the Fall of 1924 and you were Louie Greenberg, an amiable American boy who knew Whitman and Shakespeare, who could ride horseback and play baseball and who cultivated a small compassionate smile that inspired trust and confidence. Majoring in languages and literature, you quickly mastered the written and spoken terrain of French, Italian and Spanish. Captivated by Cervantes and Lope de Vega, your passion for the drama of the Golden Age became synonymous with your love of the Harvard campus. Mental and physical agility characterizes the young man I see in animated discourse with professors and classmates. Your prize winning senior thesis won the praise of visiting scholars and the prospect of a professorship at Oxford where you would complete your doctorate. A warm light would come into your eyes whenever you recalled this period forty, fifty, sixty years later as, "The happiest time in my life."

The

Golden Age was not flourishing in America when you graduated in 1928.

As we fell precipitously into a depression, neither you nor your father

would be able to finance your doctoral work. Your life at Oxford, with

its green lawns and lofty spires and ideas became a deferred dream, all

the more poignant because it was never realized. You applied your intellect

to a volatile economy, discovering in yourself a shrewd business acumen

which served you well over the next decade. You worked as actuary, stockbroker,

and finally chief executive officer of your own credit bureau.  You

bought a home on Staten Island and tenderly administered to your garden.

The natural world infused you with a lightness of mind. You spent weekends

planting and riding horseback. In 1932 a feature article appeared in a

local newspaper profiling you as an outstanding young citizen who had

read Thoreau and Whitman, attended the Metropolitan opera, practiced vegetarianism

and was intimately acquainted with the stock market. I discover a picture

taken of you at this time seated on a horse with a pretty, young woman:

you are holding the reins while she smiles sweetly behind you. You appear

round and stout and unsmiling. Your gaze wanders far from the camera.

You

bought a home on Staten Island and tenderly administered to your garden.

The natural world infused you with a lightness of mind. You spent weekends

planting and riding horseback. In 1932 a feature article appeared in a

local newspaper profiling you as an outstanding young citizen who had

read Thoreau and Whitman, attended the Metropolitan opera, practiced vegetarianism

and was intimately acquainted with the stock market. I discover a picture

taken of you at this time seated on a horse with a pretty, young woman:

you are holding the reins while she smiles sweetly behind you. You appear

round and stout and unsmiling. Your gaze wanders far from the camera.

As you chafed

in the skin of an American businessman, you would cast about for another

persona. In

1939 you joined the army, rising quickly from lieutenant to major. Stationed

in Washington D.C., you planned battle strategies.  You

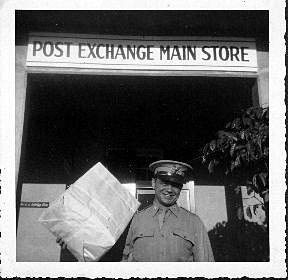

were never called to the front. I have a snapshot of you grinning under

your major's cap, balancing a bulky parcel in one hand beneath a sign

that reads Post Exchange Main Store. You seem to be showing off your territory.

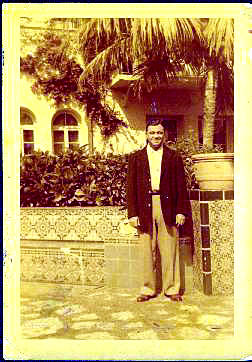

After the war, you returned to the business sector, but maintained your

affiliation with the National Guard. Your love of all things French, engendered

at Harvard, led you to visit Paris in the fall of 1948. Wandering down

Rue de Grenelle, admiring the delicate iron latticework and pristine pavement,

you decided to take the street for your surname. Once back in the States,

you scrapped Louis Greenberg to become Louis Jerome Grennell. A year later,

standing proudly in your major's uniform, you met my mother, a woman eighteen

years your junior. She had haunting green eyes and a sure, yet trembling

smile that made you vow to protect her. A year later, you married her.

My birth would fill you both with a heady sense of joy.

You

were never called to the front. I have a snapshot of you grinning under

your major's cap, balancing a bulky parcel in one hand beneath a sign

that reads Post Exchange Main Store. You seem to be showing off your territory.

After the war, you returned to the business sector, but maintained your

affiliation with the National Guard. Your love of all things French, engendered

at Harvard, led you to visit Paris in the fall of 1948. Wandering down

Rue de Grenelle, admiring the delicate iron latticework and pristine pavement,

you decided to take the street for your surname. Once back in the States,

you scrapped Louis Greenberg to become Louis Jerome Grennell. A year later,

standing proudly in your major's uniform, you met my mother, a woman eighteen

years your junior. She had haunting green eyes and a sure, yet trembling

smile that made you vow to protect her. A year later, you married her.

My birth would fill you both with a heady sense of joy.

In

my earliest memory of you, I was age three or four. You were lifting me

gently by the arms and swinging me back and forth in front of a wide picture

window. We were living in a house by the sea on the southern tip of New

Jersey. "Swing me," I shouted, "Daddy, swing me." Later in the day, you

planted rows of tomatoes in our garden. As you lay on your stomach, your

solid frame seemed to become one with the earth. In the evening, you filled

the house with operatic music. You taught me the libretto of Madam Butterfly.

Wrapped in my mother's kimono, I scouted for signs of Lieutenant Pinkerton.

Only once in these early years do I remember your fierceness. You stormed

at me because I had scrawled squiggly yellow lines on the wall above my

bed. You wanted me to be your perfect little girl. You and mother never

really fought, yet a furtive silence hung between you. At age six, I dreamed

we were living in a paper house.

In

my earliest memory of you, I was age three or four. You were lifting me

gently by the arms and swinging me back and forth in front of a wide picture

window. We were living in a house by the sea on the southern tip of New

Jersey. "Swing me," I shouted, "Daddy, swing me." Later in the day, you

planted rows of tomatoes in our garden. As you lay on your stomach, your

solid frame seemed to become one with the earth. In the evening, you filled

the house with operatic music. You taught me the libretto of Madam Butterfly.

Wrapped in my mother's kimono, I scouted for signs of Lieutenant Pinkerton.

Only once in these early years do I remember your fierceness. You stormed

at me because I had scrawled squiggly yellow lines on the wall above my

bed. You wanted me to be your perfect little girl. You and mother never

really fought, yet a furtive silence hung between you. At age six, I dreamed

we were living in a paper house.

In the summer of 1956, Mother left you. While the two of you lived separately in Manhattan, I was sent to a boarding school above the Hudson river, a safe haven of pine trees, grape harbors and gentle hills where I came to dread your sporadic Sunday visits. Your labored steps and solemn brooding expression did not belong to the father I had known. Mother remarried four years later. Her new husband was a State Supreme Court judge who was alternately imposing and jolly. When you lost your job and had to seek his help your bitterness reached a Wagnerian crescendo. Making out lists of people who had maltreated you, you asked God to perform acts of retribution. You regarded my mother as a heathen and me as a newly anointed member of the privileged class.

An angry tremble crept in your voice, a tremble I had come to anticipate and dread. When I was twelve on a cold day in February, I remember you taking me to see the Mona Lisa, which was on display outside the Metropolitan museum. As I stood shivering in the icy wind, you said harshly. "You're not Princess Margaret, Stephanie. You have to stand on line like everybody else." Surprising tenderness could cut through your resentment. Driving me back to boarding school on a snowy winter night, I recall your gentility and eloquence as you helped me prepare for a history test. The Puritans and Ann Hutchinson were your intimate friends. I was sure there wasn't anything you didn't know.

When

I was fourteen, at my mother and stepfather's insistence, I entered a

private high school in Brooklyn. While you agreed to pay the tuition,

the burden proved too great. My stepfather shouldered this responsibility,

decimating your pride and exacerbating your anger at me. Your comments

seemed designed to wheedle away at my self-esteem. "You are not a smart

girl, Stephanie. You'll never attend an Ivy League college."  Congratulating

yourself on your Harvard education, you would speak in a tone laced with

regret, "I don't know how a daughter of mine could be so slow- minded."

My character was also the target of your reproach. You were appalled by

my selfishness; I neglected to comfort you when you were alone and unemployed.

My sympathy for you lay in a complex matrix of emotions. I had come to

regard you as the Enemy. In a picture of us taken at my high school graduation,

you fill the dark folds of your suit with an embittered stoutness. Cynicism

contorts your features and your eyes look haunted. I stand next to you

in a short, white A-line dress and white patterned stockings. My long

dark hair casts a shadow across my face. My gaze darts nervously away

from you.

Congratulating

yourself on your Harvard education, you would speak in a tone laced with

regret, "I don't know how a daughter of mine could be so slow- minded."

My character was also the target of your reproach. You were appalled by

my selfishness; I neglected to comfort you when you were alone and unemployed.

My sympathy for you lay in a complex matrix of emotions. I had come to

regard you as the Enemy. In a picture of us taken at my high school graduation,

you fill the dark folds of your suit with an embittered stoutness. Cynicism

contorts your features and your eyes look haunted. I stand next to you

in a short, white A-line dress and white patterned stockings. My long

dark hair casts a shadow across my face. My gaze darts nervously away

from you.

Your remarriage in 1967 allowed you a modicum of happiness. You could bask in your new wife's admiration for your youthful accomplishments. At sixty-three, you were teaching history to preteens in a Queen's middle school. While you professed interest and stimulation in your work, I suspect that sweet breath of Oxford spring never ceased to taunt you.

After my stepfather's death in 1969, the chasm between us deepened. You warned me not to use this event to solicit pity, taking pains to remind me that he had never been my relative. Out of deference to my mother your former friends and business associates came to his funeral; I was stung by their whispers of your questionable financial dealings, dealings which catapulted Mother out of the marriage. Confronting you in righteous indignation, I caused the thread of contact between us to become even more tenuous. Your voice came as a lament through the phone in my college dorm, as I stood in a smoke-filled hallway, "Even my own daughter has turned on me."

In

the summer of 1970 you lay bleeding internally in a Boston hospital. You

were suffering from exhaustion and the sound of an erratic heart was beating

in your ear. Manhattan doctors couldn't find a cure.  Your

wife, Annette, was angelic in her concern. I visited you dutifully on

weekends. When your physician assured me that you were in no imminent

danger, I announced my plans to go to Europe. It was then that your wife

charged at me physically, exhibiting the wrath that you had taught her

to believe was coming to me. I held her thin white wrists, shouting, "I

am never coming back here." You made a full recovery later that summer.

But the knowledge of your contempt crystallized into a cold hatred; I

determined never to see you again. Casting off the shackle of the name

Grennell, I took my stepfather's name, Hart.

Your

wife, Annette, was angelic in her concern. I visited you dutifully on

weekends. When your physician assured me that you were in no imminent

danger, I announced my plans to go to Europe. It was then that your wife

charged at me physically, exhibiting the wrath that you had taught her

to believe was coming to me. I held her thin white wrists, shouting, "I

am never coming back here." You made a full recovery later that summer.

But the knowledge of your contempt crystallized into a cold hatred; I

determined never to see you again. Casting off the shackle of the name

Grennell, I took my stepfather's name, Hart.

In the five years we were apart, your shadow hovered ominously around me. I wrote papers dissecting Hawthorne's concept of the power of blackness. Both an intellectual affinity and the discomfort of holding a grudge led me to initiate reconciliation. I discovered you had aged. The lines in your face had become deep crevices, but your anger had diminished. After our initial recriminations, we never again discussed our differences. You were working in the check signing division of a Manhattan department store. Over the next decade, we would meet for lunch in your cheerless office, balancing paper plates on a gray metal desk. It was here that you would rhapsodize about your years at Harvard and the senior thesis that had so engaged you. I came to see you as a tragic figure, a character Hawthorne might have written about and discarded. In your mid-seventies, you had a final vision of forming a financial conglomerate in India. At eighty-four, two years after you retired, you died quietly in your sleep.

I felt an unexpected depth of sadness when you were gone. The following summer, I visited the Harvard campus, that fertile patch of Massachusetts's ground where you had sprung so fully to life. I discovered your prize-winning thesis in the library, the only document to remain on the shelves from the class of 1928. Reading the manuscript at a long mahogany table in a sun-filled room, I marveled at the intellectual ardor and flow of your language. Words were clay we both used with sincerity and awe.

Love and understanding were never gifts I intended to extend to you; instead, they have grown imperceptibly over the years since your death. Along with joy and accomplishment, my life has been rocked by disappointment, both personal and professional. I know how elusive love can be. I have experienced the pain of trying to create. I know the dungeon of self-doubt and self-loathing, the storm of envy that can overtake me when I see others hold what I may never have. I have known the pit of loss and longing where hatred is born. We are not alien to one another after all.

On

a recent trip to Paris, I walked down Rue de Grenelle as if in your footsteps.

Approaching the Cathedral of Notre Dame at dusk, I watched lights pull

at the roots of the sky  and

wondered which of your dreams still lingered there. Once back in New York,

I experienced you as a friendly presence at my side, an adumbration of

lightness. And then you entered my dream last night looking gallant and

self-assured in a navy blue suit, not masquerading as some bitter old

man, but again as my father sans the bitterness that distorted his perceptions

for so many years.

and

wondered which of your dreams still lingered there. Once back in New York,

I experienced you as a friendly presence at my side, an adumbration of

lightness. And then you entered my dream last night looking gallant and

self-assured in a navy blue suit, not masquerading as some bitter old

man, but again as my father sans the bitterness that distorted his perceptions

for so many years.

I would like to believe in the existence of spirit beyond flesh, which would mean that you are truly listening. I am finding that love has curative powers. By accepting others with their foibles, I am beginning to find compassion for myself. I think you would like the apartment I am living in now. My window reveals a wide breadth of sky above the Hudson River, the sun as a great white ball before it bleeds into a fiery orange. I have abundant green plants and classical music is always playing.

My cousin Judy recently gave me a restored photograph of you and your parents which hangs in my hallway in a gold frame under a soft white light. I see you at three months old in a little white smock, propped up comfortably on your mother's lap. There is a dewy expression on your face. Your toes are pointed outward. Dressed in a proper black suit behind you and your mother, your father looks handsome and aristocratic. Both your parents are shaded in sable-brown tones. You are the bright spot between them.

I can remember when we lived in the house by the sea -- you, Mother and me before the divorce. You were such a good dancer then, so light on your feet. Weightless, defying the laws of gravity, you would dart around me in my room with the spotted linoleum floor and my toys strewn everywhere: my Daddy. I have difficulty mastering steps, but I have your sense of rhythm. I feel like dancing tonight in celebration of my love for you, and the peace and good wishes I am sending you across eternity. I hope we meet again someday.

Your daughter,

Stephanie

please email ducts with your comments.