My lottery number was 169. It was not low enough to be certain of being drafted but low enough to make it probable. The year was 1969. The number had prevented me from making a serious effort at interviewing for the investment career I planned; no company was going to hire me, train me and then see me off at the station for a two year leave of absence. All I could do was graduate from Georgetown, go home, and wait it out.

There were lots of rumors, lots of advice, but no one knew anything. Each draft board was different. My family doctor, as he signed a letter describing my lifelong problem with asthma, said that he had seen guys who could play line backer for the New York Giants be rejected. Others who he would personally give his seat to on a bus were doing search and destroy missions in the Me Cong delta. To him the process seemed completely arbitrary.

Sometime late in that hot, aimless, summer of love, after the moon shot and the Charles Manson Murders, maybe just before Woodstock, a now unidentifiable, disembodied voice told me that teachers were not being drafted directly from classrooms. It probably took place in some sleazy bar or over a smoke clouded pool table. It checked out to be true. I now had a course of action; I would become a teacher. Hopefully in the next two weeks, as the school year was about to start.

I had already applied for a reserve unit, but the waiting list was very long. If I had a good nine months of deferral as a teacher, I had a shot. That was the new back up plan if the letter from my doctor didn’t work.

Today, after all the political mud that has been thrown over Dan Quale’s reserve unit service, the letter that was written to Bill Clinton’s draft board and George W. Bush’s performance in the Texas Air Nation Guard, any attempt at seeking a reserve unit status or legally avoiding the draft is portrayed as sniveling cowardice. That sentiment would have produced blank stares in that smoke filled pool hall in the summer of ‘69, if not outright snarling laughter. There had already been a quarter of a million people on the Washington mall and protests, even riots, on most major US campuses. Viet Nam was by then a very unpopular war. A lot of guys got drafted and a lot of guys went, but nobody I knew wanted to go. Nobody.

Back then there was, believe it or not, a teacher shortage. I simply opened the paper to the want ads and answered a few. I could not teach in a public school without certification, so I focused on private and parochial schools. I got some responses, interviewed, and took the first offer. The St. John’s Prep/Georgetown University part of my resume produced the expected response from Catholic schools. Let’s face it, it was August and they were pretty desperate too. The next thing I knew I was a sixth grade teacher at St Mary’s School in Windsor Locks, which was about ten miles from my home in Manchester, Connecticut.

My salary was a paltry $6,100 a year. I met with the principal who had hired me, a very nice but no nonsense nun with crystal clear, steel blue eyes, Sister Cecilia. She gave me the textbooks I was to use and a few lesson plans. There were two sixth grade classes. I was to teach Math, Social Studies and Science, and an older nun would handle Religion (thank God) and English. I tried to prepare a little, but I pretty much figured I could wing it. I was focused on other things.

A week or so after I accepted the job at St. Mary’s I got a call from the principal of major regional Catholic high school. He was looking for a History teacher and was intrigued by the fact I had taken courses in Asian history. Would I like to teach a number of American history classes and then perhaps one in Asian history for top students? It sounded great and I told him so, but I also said I had signed a contract with St. Mary’s and didn’t feel I could pull out just a few days before school started. He told me if I wanted to break the contract, I should. He could also offer me more money. This guy was a priest, but I had learned not to be shocked by such things. I had to turn him down, as much as I hated to. I could run tollbooths to save a quarter, but I really couldn’t break faith with a very nice person who had put her trust in me.

It’s interesting to think that the other job might have been so much fun, I might have considered staying with teaching for a career. My life would have been very different. You just never know.

My first day at St. Mary’s I showed up a little early and said hello to the principal and the nun who was the other sixth grade teacher. She was about fifty and seemed very capable. I then went to my homeroom and waited for my class to show up. I think it was only then it began to dawn on me how completely unprepared I was.

Sixth grade-hmmm… How old are you in sixth grade? I was counting it out on my fingers. Eleven!..Eleven? How big is an eleven-year-old? I looked out the window to the children gathering on the playground. They were all so little. I remembered my own sixth grade as though it had been the previous weekend. Was I that small when I was in sixth grade?

I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. I knew nothing. I was seized with panic. God! I’m responsible for these kids! I thought of Mrs. Boyle, my sixth grade teacher. She was so good! She had made an enormous difference in my life! My eyes focused on my reflection in the windowpane. I was no Mrs. Boyle.

I believe I became an adult that very moment. I was, for the first time in my life, responsible for someone else. I could be as reckless and irresponsible as I wanted with my own life, but I couldn’t be that with these kids. I suddenly realized this was going to be a serious challenge I would have to meet head on. After suffering through years of boring, incompetent teachers who could not hold my attention, I was not about to do the same damage to these kids. Not if I could help it.

A bell rang. The children began to come in and take seats one at a time. They still looked small. I noticed they seemed to all know exactly which seats to take. The little ones were in the front rows; the tall ones were in the back. Their feet were firmly on the floor, their backs straight; their hands were folded on their desks. These kids were very well trained. They didn’t make a peep, but all stared at me with obvious fear and reverence. I wasn’t accustomed to being looked at like that. I eyed them coolly.

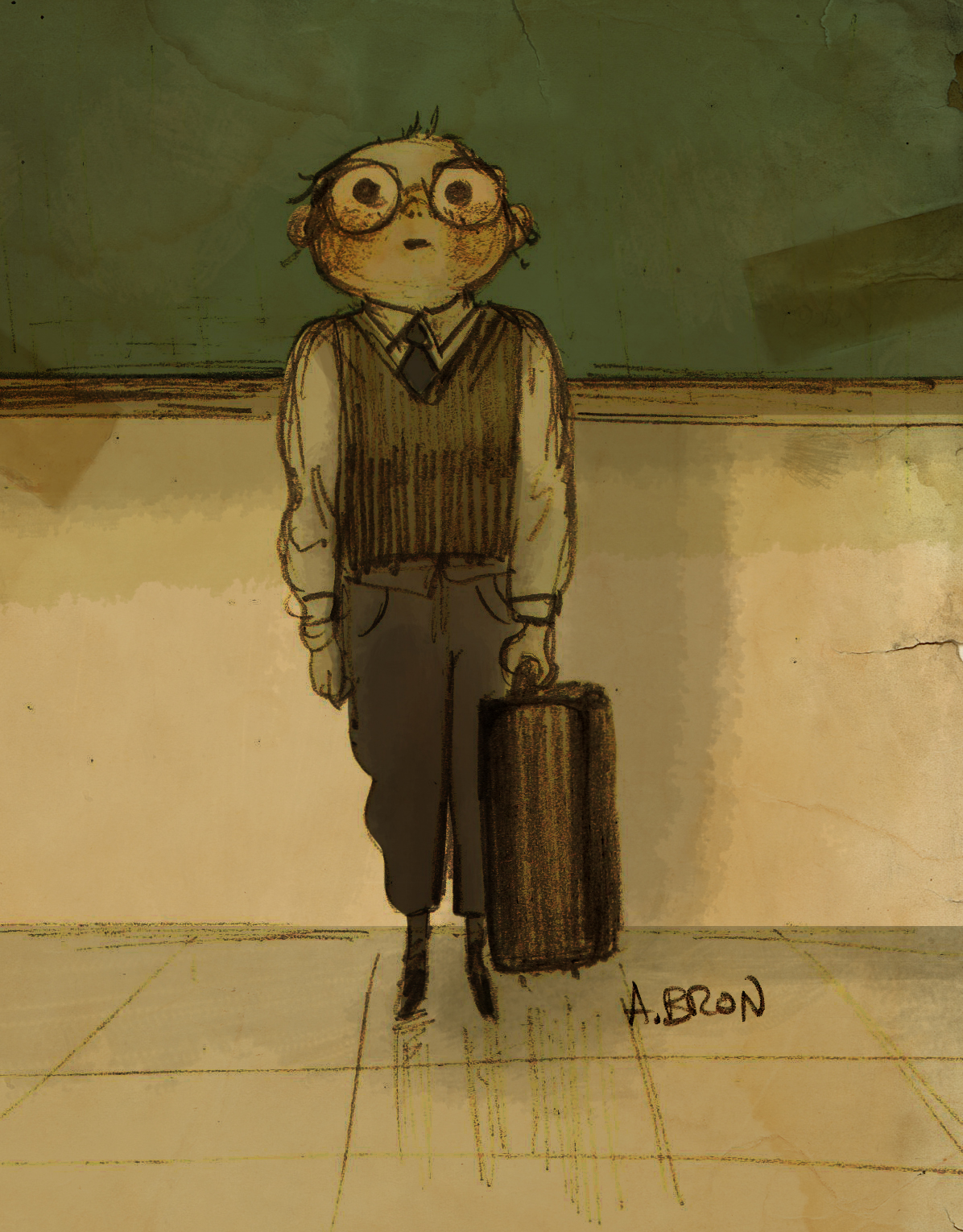

Another bell rang and I stood to speak to them. This was as close to an out of body experience as I have ever had in my life. I was watching this thin fellow of twenty-two years with his new, tailored sports coat and tie, his neatly creased bellbottom slacks and leather boots, his wavy hair, sideburns and dark-rimmed glasses. He was addressing his class. He was confident, measured, responsible and articulate. He was saying just the right things for the beginning of the school year. He was doing an excellent job. Who the hell was he? Where was he getting all this stuff? He certainly didn’t sound like me.

Then another bell rang and the class stood up and filed to the door, one row at a time. They stood there, girls one side, boys on the other. The two at the front looked around at me, waiting for my permission. For what? To go where? I had no idea what they were doing. I was still standing there, finger raised to punctuate an extremely important point to a class of empty desks, my head now turned to the two rows of eyes at the door awaiting my command. I assumed there was an assembly somewhere- I actually hadn’t even looked around the place to discover where- so I lowered my hands to my side and gave a knowing, authoritative nod. They all turned forward and moved out in silent precision.

As we padded down the hallway I did notice, with some alarm, that there were no other classes joining our procession. Then my little platoon took a sharp left and went out of the building onto the street. There was nobody following! We motored down the street. Not one kid gave so much as a sideward glance while I was frantically looking around to find some clue as to what the hell we were doing! I figured the moment had passed when I could have reasonably asked what was going on. Now I had to simply go along for the ride. But I began to visualize Sister Cecilia, hands folded in front of her, calmly asking me, “They went where? They did what? You just followed them?” Was I going to be thinking of this moment while lying in the muck of a rice paddy, Cong bullets splashing around me?

The dog team came up to the next cross street and took a right. Just as I was swinging around the corner, feeling like the guy holding on to the ladder in the back of a fire truck as it careened into an intersection, I caught sight of some neatly uniformed children marching out of the front door of the school. I exhaled for the first time in five minutes. When I had finally righted my vision long enough to look forward again, I saw it. At the end of this new street, facing us, was a church! It had a tall steeple and its two front doors were opened wide, waiting for us. We were going to church! Of course! We were going to church! How perfectly obvious. How could I have, even for a minute, felt like the Pied Piper, only in reverse, the children leading me to my doom? I quickly composed myself. I was back in control.

We proceeded to the end of the street, mounted the steps and swished down the aisle to the foot of the altar with the smartness of the graduating class on the parade ground at West Point. The troops then pealed off into the pews with the exactitude of a sorting machine, leaving, of course, the spot at the end of the first pew open for me. I, with just the right amount of nonchalant care, inspected that all things were in proper order, and then assumed my place in front with quiet dignity. After a while the church filled up with the rest of the school. I snuck a peak at the congregation. They were all, every one of them, staring at me. I turned and looked forward with regal aplomb.

The priest and two altar boys swept in front of us from the wings of the sacristy so we all stood. The mass had begun. While I was standing there it suddenly occurred to me that, despite years of attending mass, I had never paid the slightest attention to when, in the course of the proceedings, one was to stand, sit or kneel. I had always relied on everyone else and simply followed along. Actually I had never been in the front row of a church before. This could be a little awkward. I took another extremely disinterested look behind. They were all still staring at me. I figured my little mechanical sixth grade soldiers would march me through this one as well.

Well, they didn’t. They were looking for my leadership on this one. I heard rustling behind me and sat down. Fine, but the next time I wasn’t sure the sound was of standing or kneeling. Whatever it was, I guessed wrong, as the titters all around proclaimed. The rest of this interminably long ceremony was a laugh fest of my sixth grade standing when everyone else was sitting, kneeling when they were standing, some kneeling or standing or sitting all at the same time. Finally I threw off all pretenses and simply turned around to the now extremely bemused gathering to get my directions. When it was over, on the way out, I was, of course the last one to leave. Sister Cecilia was waiting for me at the door outside.

“Mr. Stack,” She bowed her head slightly.

“Sister Cecilia,” I bowed back.

“It appears we haven’t been to Mass lately, Mr. Stack.”

“Well, we haven’t sat in the front row for quite some time, Sister.”

“Perhaps we shouldn’t sit in the front row in the future, Mr. Stack.”

“You know, Sister, it is quite extraordinary, but the very same thought occurred to me.”

“Good day, Mr. Stack.”

“May yours be very pleasant as well, Sister.”

By the time I got in my car at the end of the day I was wringing wet. I pulled out of the parking offering the occasional red-faced wave to my flock on the sidewalk. They were smiling. “See you tomorrow, Mr. Stack!”

Half way home I literally had to pull the car off to the side of the road, I was laughing so hard.

As a parent and now a grandparent, this story is frightening. How could anyone have entrusted children to such a untrained boy? But I was a good teacher, for a rookie. Sister Cecelia, after observing me many times, said I was a natural. I’m certain I learned more than my students that single year of teaching, but I put a lot into the effort and they liked me very much. I think after, that first day, they were on my side. I owe them a lot.

As it turned out my doctor’s letter worked. I received a medical deferment for asthma and began my investment career the following summer. I was prepared for it because of what happened that day in September 1969.

That was the day I grew up.