When fellow third grader Erica Jergison told me about the death penalty on the playground of Forest Hills Elementary, I had reason to be skeptical. Just weeks earlier, her definition of sex as two people showing each other their butts had turned out to be wrong. My mom had explained precisely—and traumatically—how, forever changing Barbie and Ken’s relationship.

“The Bible says we’re not allowed to kill,” I told her.

“We can kill criminals.”

I was sure God would not be okay with that, and so it couldn’t be true. As the kid of not one but two Baptist ministers, I heard a lot about God. God came up everyday. Mom kept a stack of cards profiling missionaries by the kitchen table. Each morning, we took turns selecting one to read aloud.

Sam Mandela: working with nomadic peoples in the Ukraine. Wife Sandy. Loves baseball.

After that, we sang the blessing. In a round.

For health and strength! For health and strength and daily bread, we give thee thanks, oh, Lord.

In spite of all this, I developed a natural irreverence for the church early on. It was just where my dad worked, or where I spent weekday afternoons photocopying my face. On Sundays, I gave tours of the baptismal pool to other children and showed them how to steal communion crackers from behind the pulpit. And I hadn’t been allowed to ask questions in Sunday school ever since second grade, when I had upset the teacher by making the very logical point that Cain and Abel could not have procreated without committing incest.

Despite my history of rebellion, I was still the minister’s kid, and that came with perks, like the opportunity to perform a solo in church. I said, “Yes!” and promptly began concocting elaborate fantasies of the fame that would surely come my way, once the world discovered me. This would be my start, my humble beginning.

In preparation for the event, I had plastered the walls with handwritten posters on typing paper that read:

Don’t miss it!

SUNDAY OCTOBER 5, 1991

Come hear a talented young girl sing a buttifal solo titled

I KNOW GOD LOVES ME

Backed up by her third grade choir!

It will be HOT, HOT, HOT!!!

Complete with bubble exclamation points, of course.

High on the attention I had gotten—mostly geriatric—from my “hot hot hot” performance, I had asked my dad if I could be on “Star Search.” His response? A casual, “Fine with me.”

Apparently my father assumed his eight year old was bright enough to realize that her father didn’t control the world of television. But I wasn’t.

I proclaimed the news to anyone who would listen. I told them what I would be wearing—a navy dress with red shoes. What I would be singing—Wilson Phillips’ “You’re in Love.” (A song about God wasn’t going to cut it on “Star Search.” I knew that much.) And I started a waitlist for comps without knowing what comps were.

Within days, my mom was fielding calls asking when my episode was airing. I was in my room belting, “And I knoooow!” when she confronted me.

“Are you telling people you are going to be on ‘Star Search’?”

“Dad said I could.”

“It’s not up to dad! You have to audition!”

Under her relentless supervision, I confessed to each ill-informed congregant, one by one, that there would be no such episode. Also, I wasn’t allowed to claim that it just fell through.

But I’d seen how effective my bulletin had been. So two months later, when my mom explained that Erica was right about how we kill some criminals, I knew what to do. Lodged snugly between my sister and Mrs. Reece, the grandmotherly church member who fed us butterscotch candy while my mom perched in the choir loft, I scribbled onto my program with a pencil from the rack:

PETITION TO STOP THE DEATH PENALTY

The Bible says thou shalt not kill. This means no killing of anyone by anyone else.

And I signed my name:

Mary Patricia Adkins.

Then I added lines for all the other names. I passed it to my four-year-old sister who drew a picture of a dog. She passed it to the child next to her. It was out of my hands. I watched the petition move down the pew, then up to the one in front of us. Like that, it was moving. Not everyone signed it, but they continued to pass!

Until it reached Myrna Willoughby.

Mrs. Willoughby was terrifying. One, her hair didn’t move and reminded me of the purple, glow-in-the-dark bracelets that were the best thing about amusement parks. Also Lauren Powell’s birthday party.

Two, she made us call her Mrs. Willoughby, even though the other parents’ just let us say their first names. Three, she pinched children’s ears off.

I watched Mrs. Willoughby slide the petition under her Bible without breaking her focus forward. Then I counted the minutes remaining with my ears.

After the service she approached me and led me to part of the room that had emptied, where she pulled out my work. Kindly—gently—she asked why I had made it.

“The Bible says do not kill?” In my scuffed patent Mary Janes, starched satin sash and enormous hair bow, I was trembling. But I was also certain. I knew. And she had to, too—right?

“But it also says an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” she said.

I didn’t get the metaphor, but I understood that she was saying that she didn’t agree, and that God might not, either.

It had been jarring to hear that my dad couldn’t order me onto TV. Once I understood that he didn’t have that kind of power, the fact seemed obvious. I was even embarrassed by my old myopic view. But this was different. This time, I still felt right—deeply, assuredly right. Did that mean adults could be wrong? Could God?

I sat with my hands folded neatly in my lap, and when Mrs. Willoughby asked if I would think about what we had discussed, I said, “Yes ma’am.”

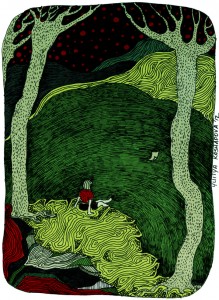

It’s hard to pinpoint when real change takes place. Like trying to identify the beginning of a hill, or the end of it. It’s always either somewhere back there, or still ahead. I don’t recall the first day I ever felt alone in the world. But I know that day, I did. I was alone, and the hill was rising, and I was rising with it.