Kenneth was a nice enough young man. During class, he was quiet and respectful. Like most of the students at Fubster College, a small public college tucked away high in the mountains in the Deep South, he was a young man without pretense. He entered class each morning, took his seat, and did his work. His grades were average, and he seemed content with this. He often chatted amiably with Lisa, the attractive young woman who sat beside him. It did not take a rocket scientist to tell he was smitten by her.

Kenneth completed his work without any fuss. English composition was a requirement. He wanted to get through the course with as little pain as possible and move on. If you asked Kenneth his goal in life, he would have replied vaguely enough, “a good job.” English was at best a minor irritation to Kenneth. He knew if he sat through class quietly and did his assignments regularly, he could pass without too much exertion or anxiety.

Kenneth completed his work without any fuss. English composition was a requirement. He wanted to get through the course with as little pain as possible and move on. If you asked Kenneth his goal in life, he would have replied vaguely enough, “a good job.” English was at best a minor irritation to Kenneth. He knew if he sat through class quietly and did his assignments regularly, he could pass without too much exertion or anxiety.

At the beginning of each semester, in my effort to ease students into a familiarity with the writing process, I assigned a descriptive/narrative essay. To jog their creative juices, I offered them the usual pedagogical platitude. “Go to what you know”: write about a subject familiar to you. Tell a story about a memorable or frightening experience. Describe a person you admire. I handed out a smorgasbord list of mundane suggestions that included big events such as a birthday, prom night, the senior trip, a special holiday; and the names of influential people, particularly parents, grandparents, teachers, and preachers. The handout even included potential first sentences and a few short introductory paragraphs for those who found writing a complete quagmire.

In return, I received mostly perfunctory essays. On occasion a student would turn in a remarkable essay about a joint replacement operation, a robbery witnessed while standing in line at a bank, a bloody beating received from a significant other, a hair treatment that went terribly awry and burned off all the writer’s hair, or the prison sentence a writer mistakenly served for an alleged murder. These were the exceptions. They occurred often enough though to keep me reading and to keep me hoping. None of these, however, prepared me for Kenneth’s effort.

Kenneth turned in an essay provocatively titled, “Hitler My Hero.” In the essay, Kenneth raised some intriguing and perhaps little known or overlooked facts about der Fuhrer.

He held the opinion that Hitler was a fashion innovator. He described in detail Hitler’s hairstyle with its shaved sides and “laid down top.” Somewhere he’d gotten the idea that “Hitler was the first person on Earth to use gel” to style his hair. Kenneth carried on about that. He wondered “what kind of gel” Hitler used and where “Hitler got the gel cause he used it first.” He assured the reader “the gel was a real good type being that Hitler’s hair always sat in perfect place on his head.” Where else it might have sat, Kenneth never mentioned.

He argued that Hitler’s hairstyle was a tonsorial model for Germany’s youth: “Young people all over the world wore Hitler’s hair.” The style carried historical import, also. It was Hitler and his hair, according to Kenneth, that influenced the Beatles’ early “mop top” style. “Without Hitler, the Beatles wouldn’t have had hair,” Kenneth claimed.

Kenneth perceived Hitler’s mustache as another fashion statement. He described the rectangular patch above Hitler’s upper lip as a “new power statement.” To make his point, he asked, “Who else had one just like it?” Just how powerful was this lip-topping affair? Mysteriously, Kenneth assumed some of its power derived from his idea that, “Hitler’s mustache drove.” He left it to the reader’s imagination to surmise how, what, or where the “mustache drove.” He left no doubt, however, about the mustache’s power: “It was a known historical fact Hitler’s mustache brought thousands to his knees.” Kenneth did not mention if this “historical fact” is still well known. We can only imagine, if it were, the number of men who would still be sporting such a look. Then Kenneth suffered what later he would admit was a severe mental lapse. Obviously forgetting the meaning of the cross dangling round his neck, Kenneth concluded his celebration of Hitler’s mustache with the exclamation, “Only the world’s most magnet mustache could have brought so many people to kneel!”

Kenneth devoted a paragraph to Hitler’s clothes and their style. To Kenneth, Hitler was the consummate fashion plate because “his clothes were always impeccably dressed.” Who dressed them or with what, Kenneth never mentioned, but he did add, “Hitler dressed up served as a model for the Russian army.” At first, this “fact” may seem inexplicable. But Kenneth may have been on to something. Perhaps he was proposing a new historical theory that historians had overlooked: that Hitler’s clothes had prompted the Russians to abandon the Soviet-German non-aggression pact of 1940 and invade Germany in 1944. The world’s a crazy place; anything is possible. After all, according to Kenneth, “Hitler set the standard in raincoats fashion around the world when they hit the floor and everyone wanted one just like it.”

Hitler’s artistic abilities transcended the merely fashionable. To Kenneth, “Hitler was a great artist.” As proof, he offered this challenge: “Just look at his pictures.” Kenneth described at length Hitler’s sad, youthful efforts to pursue a career as an artist. “Hitler went from door to door with his art. He could draw great but nobody would give him a break.”

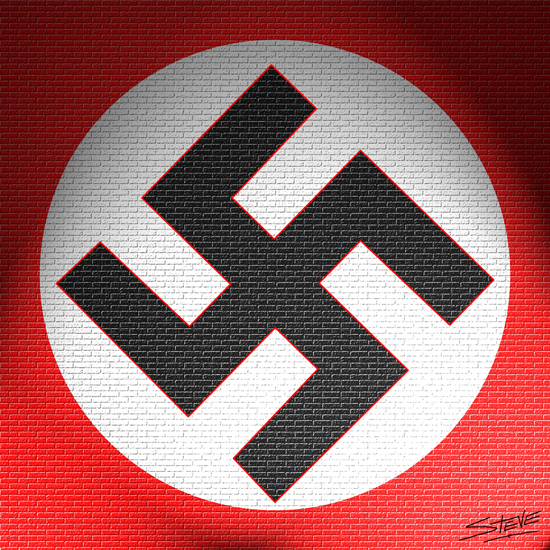

Professional jealousy was the reason Kenneth offered for Hitler’s failed art career. Teachers would not admit Hitler to art school; they were envious of his personality. “He had too good a personality for art,” Kenneth suggested. If his teachers had encouraged Hitler, Kenneth believed the “world would now remember a great artist instead of a great politican.” To leave no doubt about Hitler’s legacy as an artist to be reckoned with, Kenneth wrote, “The swaktiska [sic] is a work of modern art. Hitler drew the swaktiska and a lasting symbol to humanity was born.” Kenneth had point.

Kenneth’s admiration for Hitler was not confined to fashion and art. Kenneth could barely contain himself when he described Hitler’s “genius for moving people with his powers of speaking.” He likened Hitler to a giant generator. “When Hitler opened his mouth people were electrified.” And gassed and shot and tortured, he neglected to add. Hitler “could make anyone do anything any time he wanted to. He got things done by just opening his mouth. He got lesions [sic] of people to do his bidding.”

In Kenneth’s interpretation of history, Hitler used his oratorical skills to do many things besides “his bidding.” Hitler “opened his mouth to advance science.” When Hitler needed a more powerful bomb, “he just said to his scientists to invent the mother of all bombs, they did it without thinking.” Kenneth deserved credit here. After all, the creation of bombs often occurs without thinking. When Germany had a gasoline shortage, “Hitler spoke up and soon his scientists made the Volkswagen one of the world’s greatest cars still alive today.”

Kenneth ended his ruminations on his hero with a sentence that described Hitler’s charismatic leadership qualities. In conclusion, he exclaimed: “In all time, Hitler was the world’s greatest oiler!” Cryptic though this sentence may be, it’s difficult to argue with this concluding image of Hitler as the oiler of the machine of history.

Kenneth’s take on Hitler, if not quite original in its reverence, was uniquely his own. You might wonder what Kenneth had to say about Hitler’s involvement in World War II and the Holocaust. Don’t bother. He did not mention these events in his essay.

Grading essays is always difficult. Even after twenty plus years of teaching and evaluating thousands of student essays, placing a grade on a student’s effort is the least enjoyable part of my job. Writing is a process that one learns over time. Many of the students who attended Fubster College had little or no writing experience, in high school or anywhere else. As so many teachers in my position, I did my best to nurture students by offering gentle and thoughtful comments to right the mistakes in their thought processes, sentence structure and grammar and usage. Usually I steered away from making judgmental comments on what the students thought or believed. To explain to students the wayward peregrinations of their thinking processes was one thing. I was comfortable with that.

To teach them what to think about anything outside the world of good writing is something else. A long time ago, I realized that as a composition instructor, I wasn’t a psychologist, a philosopher, an ethicist, or a preacher. (I should note that the few times I transgressed, the administrators at Fubster College also reminded me of this.) I focused my energies on one goal: teaching the kids to write thoughtful essays that contained clearly worded sentences. When I adopted this goal, my job became easier and less stressful. Grading became easier, too.

Essays like Kenneth’s occasionally crossed my desk. One student wrote that Emily, the lonely but fiercely proud matron in Faulkner’s story “A Rose for Emily” was justified in killing Homer Barron, the Yankee laborer who was about to jilt her. The student didn’t merely sympathize with Emily’s situation and her subsequent action. He expressed a fiery belief that Emily had every right to kill Homer. In a broken prose littered with imprecations, he declared, “Homer Barron was a lying, cheating Yankee bastard and die he should have been double-barreled. It’s a good thing Emily killed him or I would of.”

I was happy to read an essay invested with such conviction and personal feeling, even if the student seemed confused about the line between fact and fiction. On the other hand,

the student’s views raised certain ethical and legal questions. I’m not a particularly brave man. I’m also originally from New York and after living more than twenty years in the South I still retained a pronounced New York accent. In this situation, what would you do?

The student’s essay was written in a language that approximated English. He didn’t grasp the idea that Emily was a sad, if sympathetic, character from a bygone era. Apparently, this student confused Emily with the likes of Lizzie Borden or Jean Harris.

I did not know how a poor grade would affect this student. I was not about to use his essay to engage him in a discussion on the circumstances or ethics of justifiable homicide. He wanted Homer Barron dead. He wrote furiously in his efforts to justify Emily’s action. During class discussion, the student argued his conviction forcefully. I tried to lead him in another direction by citing textual evidence. The student resisted. He wanted nothing to do with another line of reasoning. Homer deserved to die just as certainly as Emily had “her femine [sic] right” to kill him.

The student used his essay to show me his tenacity as a thinker and to reassure me he wasn’t about to change his mind. Still, I was concerned he should read with more insight and reason and write in the English language. On the essay, I corrected the basic writing errors. I also scribbled a few cursory comments about Emily’s state of mind and that traditions may shape one’s consciousness or expectations. I suggested he examine some telling passages in the story. These, I suggested, might allow him to rethink his ideas about Emily.

I am not proud of this, but fearing the student’s intractable commitment to his convictions, I gave him the benefit of the doubt. What doubt, don’t ask. I timidly placed a D at the top of the page. Beyond that, I’m sorry. As adamant as he was, I was not going to suggest more strongly he change his thinking on the penalty for jilting. I wasn’t taking any chances.

I offer this incident to give some insight into the problem I faced grading Kenneth’s “Hitler” essay. He did not seem a bad kid, a violent kid or, aside from his essay, a misguided kid. He had his mind focused on graduating from college and finding a good job. Actually the way he was chatting it up with Lisa, she seemed Kenneth’s most pressing goal. Still, I had to make Kenneth understand he could not separate Hitler’s methods from his crimes.

The enormity of Hitler’s charisma impressed Kenneth. Somehow he failed to recognize Hitler was in cahoots with the Devil. Since I knew Kenneth to be a decent, God-fearing young man, I figured I’d use the religious angle to explain the errors in his thinking. I wouldn’t accuse him of being a Nazi sympathizer or berate him for lacking human compassion. I would show him his mistake by methodically leading him to the conclusion Hitler was the Devil incarnate, a killer the magnitude of which humanity has rarely seen.

My simple tactic would be to point out that Hitler was a monster who trampled on the teachings of the Judeo-Christian tradition. When I finished leading Kenneth tactfully through a tour of Hitler’s murderous acts, Kenneth would see his mistake and resign himself to finding another hero. And he would naturally agree to write another essay.

I graded Kenneth’s essay as any other. I corrected the errors in grammar, usage, and mechanics. In the margins, I wrote the usual comments about problems in unity and coherence. At the top of the essay I added this remark: “Didn’t Hitler misuse his powers? Should someone responsible for untold deaths be considered a hero? Please see me.” To be sure he’d get the idea to see me and to rewrite (and to keep myself out of harm’s way), I didn’t put a grade on his essay.

As I always did, I returned the students’ essays at the end of the class period. Kenneth waited patiently for the classroom to empty and approached me.

“Hey, Mr. K. You wanted to see me?”

“Yes, Kenneth. What do you think about my comments?”

“Well, they’re O.K. I gotta look more at them. But what does this mean?” he asked.

He pointed to my comment about Hitler’s misuse of power. Good, I thought. I had his attention.

“What do you think it means?” I asked.

“I don’t know, Mr. K. I can’t read your handwriting.”

So much for a good start. After many years on the job, I kept forgetting the students’ first challenge to understanding my comments was reading my handwriting. I translated my scrawls.

Kenneth was unflappable in his hero worship. “What do you mean he misused his power? Hitler was a great leader.”

I thought Kenneth was being evasive, that he did not want to confront the facts. I frowned at him. It was not an accusatory frown, just one of those furrowed looks I adopted to let a student know he wasn’t thinking clearly. Kenneth returned my look with one of his own, a blank stare. Was it possible he didn’t know I was referring to Hitler the hooligan, the madman murderer of millions?

Kenneth kept looking at me. The longer he looked the more his eyes reflected the uncomfortable question, “huh?” When I realized Kenneth somehow did not understand my question, I quietly asked him, “Kenneth, what about the Holocaust? Didn’t Hitler use his gift of gab, his “powers of speaking” as you put it, to kill millions of people?”

I threw in the colloquialism to let Kenneth know, if he had any doubts, I was on his side. I was a good guy, a facilitator (in the language of the pedagogical trade), not a tyrannical judge who with the stroke of a pen could easily delay his career aspirations. I wanted to present myself as a guy trying to straighten out some wayward ideas. I thought a cute phrase might make him agree more readily with me.

He missed the point. It didn’t register with him. How do I know? Simple. He threw his head to the side and gave a short, quick laugh, more a snort really than a laugh. Then he wagged his head a few times. His reaction was evidently the physical equivalent of the question, “You’re kidding, right?” He looked back at me to see if this gesture, offered as an answer, was sufficient.

There was no way I was going to let this pass for an answer. I didn’t respond and waited calmly for a verbal reaction. I was prepared to wait until hell froze over. It didn’t take Kenneth long to get the idea.

“Oh that. Come on. Hitler never made that Holocaust thing.” Kenneth was now looking at me with the same expression I imagine I’d worn when I was nine and Mrs. Milner, a nurse and my best friend’s mother, took it upon herself to explain to me how babies were made.

I was as amazed at Kenneth’s response as he was at my question. I kept calm. I didn’t let my sense of outrage or disbelief overwhelm me. “He didn’t?” I asked. “Then who was responsible for the Holocaust?”

“Come on, Mr. K. You know. It was them Jews. They made up the whole thing.”

“You’re telling me Hitler was not responsible for the Holocaust, for killing six million Jews, and gypsies, and Catholics, and sick and disabled people of all ages and races?”

I gave him a laundry list of victims to emphasize Hitler’s brutality. I thought this would awaken Kenneth to Hitler as the mastermind behind these atrocities. Nothing doing. Kenneth just shook his head to let me know that whatever else was knocking around inside his skull there was no connection between Hitler and the Holocaust.

“Why would the Jews invent such a thing?” I asked, trying as best as I could to hide my incredulity.

“They wanted people to feel sorry to them.”

“Why would they want people to feel sorry for them?” I asked.

“So they could get some land to make a home country. What’s it’s called? You know the one. Isram, or something like that.”

For no reason in particular, since reason had left the room anyway, out of curiosity I wondered aloud, “Where were the Jews living if they didn’t have a homeland?”

“Mostly most of them were living in the desert somewhere. They were always looking for a place to live.”

Apparently, Kenneth was nurturing the notion that the Jews were still wandering. I was getting no place fast. I had to change direction, before anger replaced my professional demeanor and my disbelief. Then an unhappy thought crossed my mind. If Kenneth didn’t come around, he might become the first of my own Holocaust victims. But I couldn’t abandon my pedagogical patience or self-control. I had too many questions to ask. After all, my purpose was to teach. Even if we’d left composition behind, it was my civic duty as a citizen of these United States to let Kenneth know his head was filled with an ocean of historical misinformation. I struggled for equilibrium. I changed gears again.

“Didn’t Hitler and the Germans start WW II?”

The ever-polite Kenneth responded, “No, sir. It was them Japs. They bombed the sea off a California in an air raid. That started the world war called two.”

The more questions I asked, the deeper I sank into Kenneth’s delirious version of history. I felt trapped. But I couldn’t give up. Given his answers, I asked Kenneth if he learned about WW II in high school.

“Sure. That’s what got me interested in the Hitler to start. My teacher, Mrs. Wade, was a big Hitler fan. She knew all kinds of stuff about him. She taught us what a powerful leader he was. She told us Hitler was one of the most motivational speakers of all time.”

“Didn’t Mrs. Wade teach you about the Holocaust? Didn’t she teach you about the concentration camps? You have seen pictures of concentration camps, haven’t you? People walking around emaciated, just skin and bones. The dead dumped into trenches. Rotting corpses piled on top of each other. You’ve seen these pictures, haven’t you?

“Yeah, I seen movie pictures of them Mr. K. I never saw any in person.”

I was too far gone to assure him he was blessed never to have seen any in person. “Well, what about the pictures you’ve seen? Wasn’t Hitler responsible for these atrocities?”

“Come on, Mr. K., you know.”

“No, Kenneth, I don’t. Know what?”

I did not “know what.” I was feeling rigid and hot. What was happening here was difficult to understand, but not nearly as difficult as what Kenneth was about to say.

“The Holocaust and all that stuff it’s all, you know, just movie magic.”

That did it. I lost my composure. My anger flashed out.

“Movie magic!?” I exclaimed.

Kenneth remained composed, almost detached. Did I detect a touch of sympathy (or was it sadness) in his eyes? He was wondering what all the fuss was about. So he tried to set me straight.

With the calm of the veteran explaining the complexities of the game to a rookie, he said, “All that’s done with actors and computers. It’s all special effects. My brother told me about it when I was a kid. He once took me to that Jewish movie I saw, too, Shicker’s List. My brother knows lots about movies.”

“Shicker’s List,” the name shot though me like a belt of Johnnie Walker Red. I could hear my orthodox grandfather cry from his grave, “What is this with the shiker already? Ugh! It’s this boy is drunk with not knowing.”

“Schindler’s List!” I involuntarily exploded.

“Yeah, that’s the one. That was great. That commander guy picking off guys from his window and shooting them like they was just ducks in the water; now that guy could shoot. I mean he was drunk and half dressed and tripping over himself.”

“Kenneth, that was an atrocity! Didn’t that upset you?”

“Well, yeah, kind of. But it was just a movie.”

“No, Kenneth, that was real. I don’t mean the movie was real. It was based on something that really happened. In history. Schindler’s List was a recreation of history. Oscar Schindler was a real man who jeopardized his life. He sacrificed his life savings to save the lives of more than a thousand people. In Nazi Germany, there were people just like that commandant. The commandant in the movie was based on a real person. His name was Amon Goeth, just like in the movie. The Nazis killed people randomly and indiscriminately. They had a complete disregard for people who were not just like them. The movie is based on fact. Lots of books have been written about the Holocaust. Many other movies and documentaries have been made about it.”

I thought if I kept repeating myself, Kenneth would believe me. Kenneth was undeterred.

“Mr. K., are you sure? I know that movie was made by Steven Spiller or something, wasn’t it.”

“Spielberg, yes. So?”

“He’s the man who made E.T. and the Poltergeist. E.T. was so great a movie. E.T. was really cute. And when he rode his bike over the policemen’s heads to escape. I really remember that.”

The ever polite Kenneth continued, “I don’t mean no offense, Mr. K. You’re not going to tell me that was real, are you? Or in Poltergeist when the little girl goes into the TV. That’s not real.”

“Yes, Kenneth, you’re right. What do those movies have to do with Schindler’s List?”

“Just that Spellman has a real great imagination, that’s all. He could think up anything. Besides he’s Jewish, too. I know that from his name. I mean why would he want to show the whole world Jews let themselves be killed like sitting ducks and not fight back? Come on, he had to make that movie up.”

Kenneth kept piling it on. I felt like Ali in the fifteenth round of the “Thriller in Manila.” I was beyond exhaustion, but I had to stay up and keep punching.

“Kenneth, he didn’t make it up. You think the Jews wanted to be sitting ducks?

“They sure didn’t put up too good a fight.”

“Don’t you know they were overwhelmed and unarmed? Didn’t you feel bad or horrified the way the Nazi’s treated them, killed them mercilessly?”

“Yeah, well yeah, I did; but I thought it was just a movie. You don’t feel bad when someone gets slashed in a Nightmare on Elm Street movie. It’s kind of funny actually. When the guy was pickin’ off the Jews, he was kind of funny. He was stumbling around and just shooting. I didn’t think all that stuff they did to the Jews was real. That’s all. I’m sorry.”

Kenneth was sorry. He wasn’t a kid who would consciously tie me in knots. He was just a young man who had some delirious ideas about Nazi Germany and “the world war called two.”

Since my efforts to right Kenneth’s historical vision were going nowhere fast, and since I was out of patience, I asked, “You believe me, Kenneth, when I tell you Hitler was a vicious killer and the Holocaust was real?”

“If you say so, Mr. K. You’re a good guy. You wouldn’t lie to me.”

I could tell Kenneth also had reached the end of his rope. He was now more intent on appeasing me than believing anything I said. He wanted to get out of there. He was not completely convinced. Who would be if your whole life you had watched slasher movies that propelled you into paroxysms of laughter?

So I said, “I’ll tell you what. Meet me in the library tomorrow. We’ll check out some books on WW II and Hitler and the Holocaust. You read them and we’ll talk again.”

Kenneth was compliant. He did read some books about the Holocaust. He came to me, and we discussed what he read. After our talks, Kenneth had a new take on Hitler. I’m happy to say, der Fuhrer was no longer his hero. I told him I was proud of him. Not every student would take the initiative to learn. I asked him if he learned anything else from his readings.

“Maybe I found a new hero,” Kenneth said.

I was encouraged. “Good. Who is he?” Was Kenneth thinking of Eisenhower or MacArthur? Maybe Roosevelt or Churchill.

“When I was reading about Hitler, there was another man in Germany. He was a great writer and speaker. I might want to read his books. And he was a great family man with lots of children. I like that. His name is Joseph, I think you say his name like, Go-bells. Is that how?”

“Go bells,” cow bells, church bells, sirens; they all began to clang riotously in my head. I was about to tell Kenneth, “and Joseph Goebbels was such a great “family man” he took his entire family with him right into his suicidal grave!” When suddenly I had a sinking feeling. A sense of vertigo gripped me; I felt tipped to the edge of Kenneth’s corkscrew version of world history. What did Yogi Berra say, “Déjà vu all over again”? I struggled mightily to maintain a sense of equanimity. I focused intently to hold onto my equilibrium. As I tried to stabilize, I was reminded of the only thing I am 100% certain of when I teach. I never know what the hell the students are learning.