Tonight I take on the identity of Physician.

One hundred and fourteen brand-new medical students milled expectantly, many with their families, in a large university hall that reminded me of a hotel ballroom.

Tonight I take on the identity of Physician, the familiar chattering voice in my head was unusually somber that night, Physician. Doctor. Really?

The cavernous ceiling, ornately trimmed with dark wood moldings, arched over worn wooden floors and plaster walls hung with historic university photos. This is my medical school. The students were dressed up for the occasion in slacks and skirts. These people are my classmates. I scanned the college-kid faces, trying to see the doctors they would become.

It was our first week of medical school, and the entire freshman class of the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine was gathered for the White Coat Ceremony in a drafty old stone building. I knew I was about to symbolically embark upon a life-changing journey, but I felt like a college student at just one more university function. Tonight I take on the identity of Physician. It was surreal.

“Hi Jennifer,” the classmate I’d sat with during that morning’s orientation lecture waved and bounded over to me. She wore a grey skirt suit and had her hair pinned into a serious-looking bun at the back of her head. Her wide eyes and huge grin betrayed her little-girl excitement despite her effort to look professional. She was an honors graduate from one of the Ivy-League schools…Brown? Dartmouth? Her alma mater—and her name—evaporated from my memory.

“Hi…” I smiled back at her. Oh God, what’s your name?

“So, what do you think will happen tonight?” Miss Ivy-League half-whispered.

“I don’t know. Seems like an initiation of sorts.” Name...? Ugh, does it start with a “P”?

“A rite of passage—yeah, that makes sense,” her grin faded reverently.

“Looks like we’re really going to be doctors someday,” I said, trying to sound reverent, too. Peggy? Patty? Shit!

“I know. Can you believe it? And we’re at Pritzker!” She giggled nervously, returning to her excited grin, “Did you know 6,000 people applied for our class of 114?”

“Wow. I didn’t realize that.” 6000 applications?? How the hell did I get in here?

We both glanced around the room, studying our classmates.

“There must be some amazing people here. I have no idea how I got in,” said my nameless future colleague, giggling again.

I smiled at her, “I was just thinking the same thing.” Do we all feel this way?

Our shared moment of self-doubt was interrupted by the announcement that the ceremony was about to begin. We made our way to one end of the hall, towards a low plywood stage with five rows of plastic folding chairs for the medical students and participating faculty. I took a seat in the second row near the heavy mahogany lectern adorned with the University seal. Tonight I take on the identity of Physician. My internal mantra continued, as if I was trying to convince myself. The fifteen rows of folding chairs facing our stage were now filling up with family and faculty. Single and far away from home, I had no family in the audience. Bathed in the gaze of those beaming strangers’ faces, I fleetingly became a small, lost child. The loneliness ached far below my smiling excitement, but I didn’t let it show.

The purpose of this ceremony was to formally welcome us medical students into the ranks of physicians. We were to be called up individually and given our white coats (a gift from the school) and a stethoscope (a gift from a medical equipment company). As the white coat slipped onto my shoulders, I would be admitted into an exclusive club of healers who serve at the highest level of knowledge and responsibility. By accepting that coat, I would commit to seeing a long, difficult journey through to its still-murky destination. I also committed to traveling that road with dedication to excellence.

We settled into our seats, and the ceremony began. Speeches about our shining futures and the importance of our chosen path wafted over me. I was pleasantly basking in the glow of my glorious potential when I was abruptly jarred by the Medical School Dean’s deeply resonant voice, “ … as you fulfill your calling…” My calling??? I knew that I was interested in science and that I had a desire to work with people rather than alone in a lab. To me, medicine seemed like a good fit for my strengths and preferences in a career. It made a lot of sense to me. But was it a calling? Probably not. Was that required? I hoped not. I hoped that it would be enough for me to want to use my talents in the service of fellow human beings.

Dad was disappointed in my choice. Maybe I shouldn’t be here. My thoughts drifted back to that painful phone call two years earlier. Until my junior year of college, I had been planning to get a PhD in genetics. My father, a brilliant man who had not had the opportunity to go to graduate school, was very enthusiastic about my PhD plan. It appealed to his sense of intellectual hierarchy—the PhD is the most advanced degree, and that seemed like just the right level of accomplishment for me, his highly accomplished oldest daughter. He loved the idea that I would be “Dr. Hasenyager”, the first person in our family to earn a PhD.

As I dialed nervously, ready to tell him my news, I knew he would be surprised by my change in career plans. What I didn’t expect, however, was the lasting impact of his words:

“Hi Daddy,”

“Hello! How’s my girl?”

“I’m good. I have some news for you,”

“OK. What’s your news?”

“I’ve decided to go to medical school instead of getting a PhD. I learned a lot working in the lab this summer, but it was really lonely and isolating. I want to work with people. Medicine combines science and people.”

Dad was briefly silent, and then I heard his controlled inhale as he prepared to speak. “You know, Jennifer, medicine isn’t really science.” He was matter-of-fact, almost chatty.

His casual disapproval sucked the breath out of my body and scattered my carefully constructed pyramid of logic like a house of cards. Medicine isn’t science? It isn’t good enough for him? Stunned, I somehow gathered my words back together and mumbled, “MD’s can do research just like PhD’s, Dad.” I then lamely tacked on, “I’ll still be Dr. Hasenyager.” The tense conversation didn’t last much longer, and my Dad never repeated his initial disapproving remark about medicine. Despite his rapid shift to supporting me, his early and honest reaction sewed the seeds of doubt that were in full bloom as my attention returned to the White Coat Ceremony.

Do I belong here?

I shifted in my wobbly chair, listening to the slow reading of our 114 names. I watched classmates summoned in turn to receive their white coat. Returning to their seats, some of them were shining with pride. Some of them were scared to death. Many looked as if they didn’t quite inhabit their coats. A few seemed completely comfortable. One classmate was oddly blank—as if he were numb.

Lulled by the monotonous ceremony, I drifted into another memory from just a few months before:

I was trying to read my smutty historic novel, passing the time on a flight back from Chicago to New York during the spring of my senior year of college. I’d been visiting the University of Chicago campus as an accepted medical student and was returning to Cornell to finish the last few weeks of classes. During my visit in Chicago, I had struggled to imagine myself walking the halls of the hospital dressed in scrubs and a white coat, on my way to take care of a patient. Until that visit, I’d been focused solely on getting into medical school. Now I was contending with the reality that I was about to become a physician. I read the same paragraph in my book several times over, unable to concentrate on the heroine’s imminent deflowering—consumed instead with the mystery of my life as a doctor.

DING DING DING DING. I looked up from my book and saw, twenty rows ahead of me, a person’s hand reaching up to the flight attendants’ call button, pushing it over and over again. I’d never seen that before. I certainly never pushed that button. I’d always put flight attendant call buttons in the same “emergency only” category as fire alarms and red STOP buttons in elevators. And I definitely would never consider pressing it repeatedly.

DING DING DING DING. Wow, this person’s persistent. They must really want another Coke.

I tried to go back to my reading.

“May I have your attention please, is there a doctor on the plane?” The flight attendant’s voice was clipped and tense, “If so, please ring your call button and identify yourself.”

My head snapped back up. I looked to the front of the plane, where the call button had been ringing. There were two flight attendants standing in the aisle, lifting an unconscious passenger out of his seat and to the floor. I couldn’t see much else from my where I was sitting, but I could tell they were starting CPR.

“We have a medical emergency on the plane.” The carefully controlled voice explained, “Please remain in your seats. If there is a doctor on board, please identify yourself.”

Thank God I’m not a doctor yet.

The stunningly true thought slipped through my thin veneer of pre-med confidence too quickly for me to deny it.

No one’s ringing their button.

I watched a tall man in a flannel shirt stand up and move forward down the aisle.

Is he a doctor? He doesn’t look like one. What’s wrong with that guy? Did he have a stroke? A heart attack?

No one else seemed to be crying or upset, and so I assumed that this sick passenger was traveling alone—dying alone. I was certain that he was dying.

Oh my God, next time I hear someone call for a doctor, I’ll be on the hook. A life will be in my hands. What the hell am I getting myself into? I don’t want this. What if I can’t save him? What if I don’t know what to do?

I watched the guy in the flannel shirt take over the chest compressions for the flight attendant. I didn’t even know that they were called chest compressions then. I watched flannel shirt guy do CPR while the flight attendants got the cabin ready for landing. I couldn’t stop watching.

Thank God that’s not me. What’s wrong with me? I should want to help. Oh, thank God that’s not me.

The chattering voice in my head went on incessantly. I was breathing fast, my chest tight and heart pounding up into my throat. I couldn’t look away from the increasingly hopeless resuscitation—none of us could. As we landed, we were all instructed to remain in our seats until the ambulance crew arrived. As the poor dead man was rolled off the plane, I wondered how the guy in flannel was doing. He’d just been working on a dead guy for more than an hour.

That will be me next time. What am I signing up for?

I’d been deeply ashamed of my panicky reaction on that plane and had never mentioned how I felt to anyone.

I tuned back in to the ceremony, noting that my name would be called soon. Do I want to do this work for the right reasons? Is it OK that I chose medicine because it seems that I’ll enjoy it and be good at it? What about helping others and doing good in the world? Am I altruistic enough?

What about my classmates who speak of their lifelong wish to help others? Do they deserve this white coat more than me? Or the classmates who say they’re just following in a parent’s footsteps? Do I deserve that coat more than them because they don’t even seem to want this job?

The ceremony again required my attention—it was my turn to go forward and assume the mantle of my chosen profession.

As I walked up and received my coat and stethoscope, all of the chatter in my head was quiet. I saw the faces of other people’s families looking at me with respect. I felt the slight weight of the coat on my shoulders and the heavier weight of the stethoscope in my hand. I was different with the coat on. Every person in that audience viewed me as a physician in that moment. Every person who saw me wear that white coat from then on would view me as a physician. I began to feel the power of the coat. And I began to feel the responsibility. It didn’t feel like college any more.

I can do this. I deserve to be here. Tonight, I take on the Identity of Physician.

I straightened my shoulders and, for the first time, I pretended to feel confident in my white coat.

Gross Anatomy and Grandma Anna

Gross Anatomy is a rite of passage so universal in medical training it has become a cliché. There is good reason for the course’s fame—it is a profoundly altering experience to take apart a human body. Our gross anatomy lab was located on the first floor of one of the biology buildings on the main campus—not in the medical center. It was in one of the old stone buildings, and the huge windows were all painted black so no one could see inside from the nice courtyard lawn on the other side of the wall. We worked in teams of four first-year medical students, and I had a good team: Two women, two men. Two leaders (me and one of the guys) and two followers. No budding surgeon who insisted on doing all of the “work” (I didn’t yet know I would become a surgeon). Two quick-studies and two more sedate in their pace. We all got along very well, which was not true of some of our neighboring teams in the lab. Each team was assigned a cadaver (a dead body) for the six-month course. The lab was large with very high ceilings, a linoleum floor, and about two dozen waist-high stainless steel tables just large enough to fit one person lying down. On the day we first “met” our cadavers, we all walked into the lab and found our team’s assigned table upon which lay a human body inside a plastic body bag—just like the morgue on TV. With the bodies in the room, we were introduced to the odor of the chemical preservative that was necessary to prevent decomposition. It was the sort of odor that got into your nose, soaked into your hair and clothes, and imprinted itself on your brain forever. We all kept a set of scrubs in lockers at the lab building. The scrubs were necessary not so much because what we were doing was so messy, but because we didn’t want that smell on our clothes and in our homes.

On the first day of anatomy lab, our main task was to unzip the bag and look. We were also given the information cards that come along with each cadaver. On the card is recorded the age, gender, and cause of death. That’s it. No name. No story. Our cadaver was a man in his 70’s who died from sepsis. I had never heard of sepsis, but I learned very soon that sepsis means overwhelming infection in the blood—usually from bacteria.

When we unzipped our bag, we saw that our cadaver’s head was wrapped in large pieces of cloth, as were his hands. The rest of him was naked—no hospital gowns needed in anatomy lab. Near the end of the first lab period, we were instructed to unwrap our cadaver’s head. He had a full beard, a bald head, and a sharp, prominent nose that was flanked by bushy eyebrows and deep-set blue eyes. His expression was peaceful. And his brain was missing—standard procedure for cadaver preparation, apparently.

Before that day, I’d wondered if I might be upset seeing a dead person for the first time. Surprisingly, I felt pretty good—curious and calm with just a touch of queasy nerves. In retrospect, I realize that I was soothed through that first exposure to human death in part by the church-like reverence of the old lab space. I unknowingly sensed my place in the solemn dignity of that room’s past, present, and future. As I left the lab, I wondered if I might be upset cutting our cadaver for the first time. I soon learned that the first incision is easy.

The day we began our first dissection, we were instructed to turn over our cadavers so their backs were facing the ceiling. Each team was then given a copy of the dissection manual that would lead us through every step we were to take for each class. The manuals were dog-eared spiral-bound books that had seen many years of use, and they were indelibly infused with the anatomy lab smell. No way those books would ever be brought home for studying.

The very first dissection was of the muscles of the upper back and shoulders. Someone on each team needed to be the first one to pick up a scalpel and make an incision as illustrated in our manuals. To be honest, I can’t remember who on our team made the first incision—I don’t think it was me, though. I do know that I took part in that first dissection and that I was so fascinated by the truly extraordinary structure of the human body—even back muscles and nerves—that I lost awareness of the fact that this had very recently been a living, breathing human being. At the end of that first lab session, the four of us on the lab team had bonded together in an act of extraordinary intimacy and privilege, and we knew it. I felt energized by the intense experience and glad for the support of my team. I was aware that I had crossed a boundary into the taboo territory of death and mutilation; I was transformed rather than disturbed.

A few weeks into the course, my great-grandmother died. Her name was Anna and she was the first relative to die in my family since I was six. Grandma Anna was my mother’s mother’s mother, and she was the last of the immigrant generation of my family. She was born in Lithuania and had come to America in 1900. She was 105 when she died, and she had remained lucid throughout her long life. She lived in the Chicago area along with my great aunt, so the funeral was held locally. I was able to attend the funeral without traveling, and therefore, only missed one day of school: the day of the funeral itself. This was the first funeral I had ever attended, and it was an open-casket service. I had known Grandma Anna throughout my life and had visited her at least every other year. She had always been very old in my memory-she was in her 80’s when I was born—and I had had few meaningful conversations with her, maybe none. But my mother grew up with her as a member of the household, and I had come to know her through the stories my mother told.

As the service began, I sat with my family in the front row. This was the first time I had seen the casket, any casket, and I couldn’t look away. From where I sat, I couldn’t quite see into the casket far enough to see Anna. I could just see part of her pink suit—I recognized the suit from one of her recent birthday parties. Once she hit 100, the family made a point of having a birthday party with everyone there each year. Sitting at the service, I remembered saying goodbye to her each year as if that would be the last time. I remembered her thick Yiddish accent and how she was embarrassed of her snarled teeth, so she would try not to smile with her mouth even as she smiled with her eyes. I remembered her hands. She had been a seamstress and hat-maker. She’d made all of my mother’s childhood clothes. I had a pile of dolls’ clothes that Anna had made from the scraps of material used for the family’s clothes. I wondered what her hands looked like in the casket, but I couldn’t quite see.

As the service ended, our front row of family filed past the casket first. I looked at Grandma Anna’s closed eyes and uncharacteristically peaceful expression.

Her face is the wrong color.

Fleetingly disoriented, I scanned the rest of her form. Her hands were folded across her stomach quietly. That was wrong, too. Her hands were always busy—plucking at lint, rearranging a knick-knack, offering a candy. I knew that her hands couldn’t move any more, but their stillness disturbed me.

I wonder what our cadaver looked like alive. How he moved.

I watched my mother and grandmother cry, and I felt so sad for them. But no tears came for me.

When I returned to Anatomy lab the next afternoon, I was glad to be back with my friends and ready to catch up on what I’d missed the day before. We were working on the front side of our cadaver that day, and his face was uncovered. As I got to work on the next dissection, I found my thoughts drifting relentlessly back to Grandma Anna’s face in the casket the day before. I felt my heart rate speed up and my breathing get shallower. My hands started shaking just a little. I couldn’t keep from seeing Anna’s face on our cadaver as I worked.

Just hold on and keep going—this is only a reaction to the funeral. Keep it together. You can’t miss any more lab time. Keep going.

I then realized I was no longer moving, I was just standing there and staring at the cadaver—frozen. My team stood there looking at me questioningly.

I have to make this stop. I have to get out of here.

I put down my instruments and told them I needed some air. I walked out of the lab building to the courtyard outside, my head filled with images of Anna and the cadaver, all blended together. I was crying and shaking and pacing around near the door of the building in my stinky anatomy scrubs. I wanted to run away. I wanted to go back in. I was furious with myself for having this melt-down now.

Why couldn’t I cry at the funeral like a normal person? This is humiliating and interfering with my education. Get a grip, Jennifer. You’re wasting time out here.

As I berated myself in the chilly stone courtyard, my anatomy team showed up, all three of them, in their stinky scrubs. They simply came to me and put their arms around me. Someone said, “Your grandma?” And I nodded. We huddled there silently together, my team’s support and understanding warmed me as much as their bodies did. After a minute or so, I realized that I was keeping us all from our work in the lab. I took a deep breath, broke free of the group, and said, “Let’s go back inside. I’m better now.” Following my smelly teammates back inside, I squeezed the choking sadness from my throat down into my chest, willing it to stay out of my way. I didn’t have any more time for crying—I had anatomy lab. That invisible act of will was Disconnection 101, the first of many lessons in how to detach from my emotions in order to function as a physician.

First Patient Interview

Another of our first-year courses was called Introduction to Clinical Medicine. In contrast to the ancient tradition of gross anatomy in medical training, this class was quite progressive for its time. Rather than waiting until the third year, our medical school integrated clinical training from the start of the first year. We were taught how to take a medical history and conduct a patient interview in a professional, medical manner. One of our early assignments was to go into the hospital and interview an inpatient (who had agreed ahead of time to participate). I was in my third week of medical school on the day of my first patient interview.

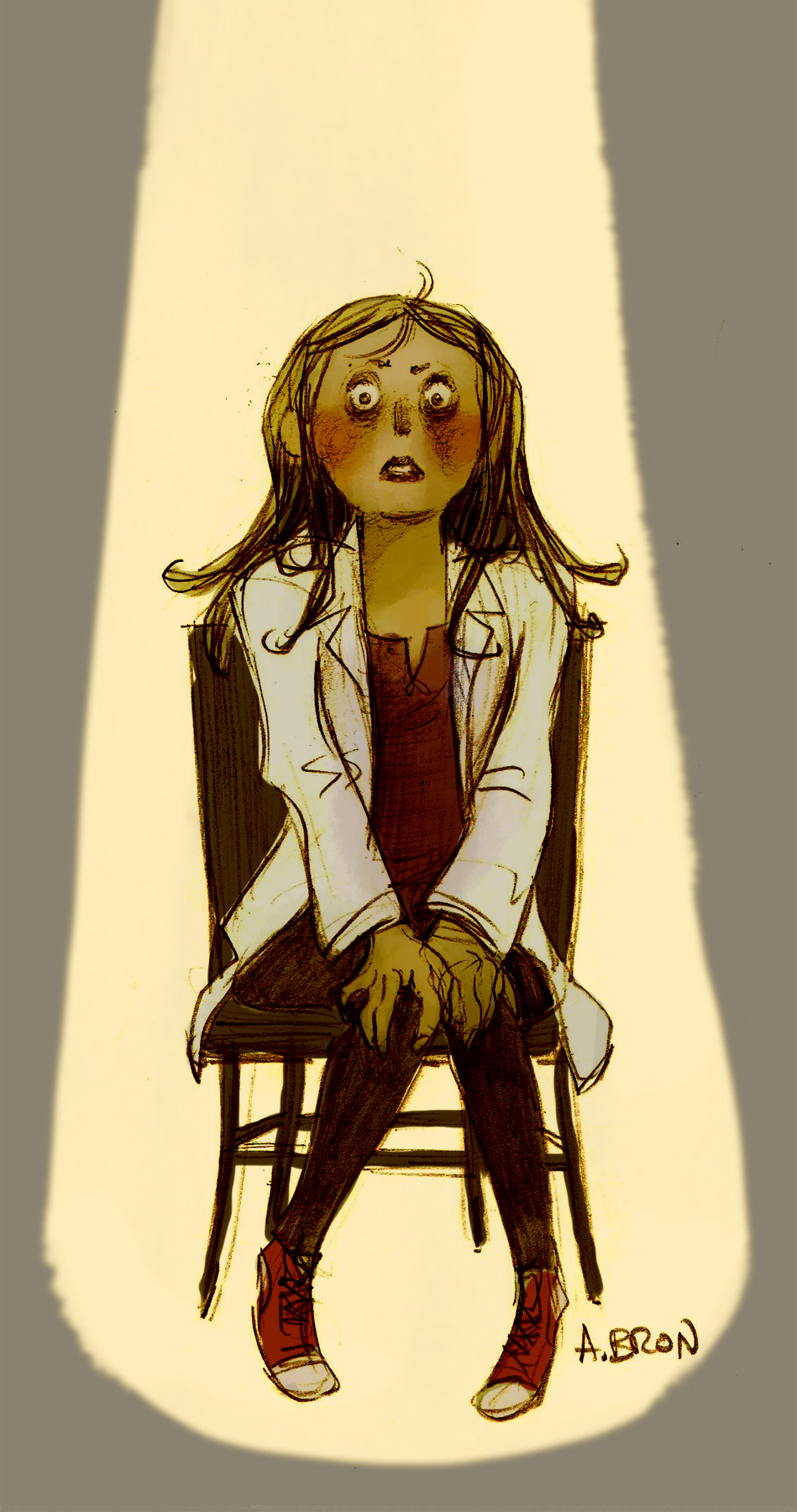

Since the majority of our classes were not held in the medical center, I had not yet been to the inpatient wards of the hospital. I set out from the medical student lounge, which was located in the basement of the building adjacent to the hospital (our lounge was right next to the morgue—to give a sense of our relative position in the medical universe). On that day, I had worn a skirt and blouse rather than my customary jeans and sweatshirt. Before I headed toward the hospital, I pulled my white coat out of my locker, where it had hung since the White Coat Ceremony a few weeks earlier. I nervously put it on and looked at the young doctor in the mirror.

Wow, I look a lot more confident than I feel.

As I walked down the long corridor toward the hospital, I passed the dozens of framed medical school class portraits that lined the walls. I looked at hundreds of faces of past graduates—now all physicians. They all looked so competent and smart and… solid. It was hard to imagine any of them feeling as unsure and lost and scared as I did at that moment.

My picture will be on this wall in four years. How?

I kept walking at a brisk pace with my head up and my face composed. I carried – or rather, clutched with a death-grip — the leather folder I’d just been given as a college graduation present.

Who gave this folder to me?

Inside the folder, which my sweaty hand was probably staining, were the notes with my patient history questions.

As I neared the hospital building, I began to pass more medical people and fewer administrative people. I saw an increasing number of physicians walking past in their white coats. I kept glancing down at myself, wondering if my hospital ID was properly displayed and whether my white coat looked right.

Buttoned or unbuttoned?

I reached over to button my open coat.

No! Don’t fuss with the coat now—you’ll look even more clueless.

My hand dropped back to my side. I kept walking, staring straight ahead, heart pounding.

Oh God, they’re all looking at me and they all know I have no idea where I’m going or what I’m doing.

The paranoia took hold. I expected one of the hospital staff to stop me and question my presence there. It was only moments before someone would figure out I was an imposter—disguised in a white coat.

As I approached the nurse’s station near my patient’s room, I saw a handful of nurses and doctors sitting and standing around the counter. I needed to check the “white board” at the nurses’ station to confirm the room number. A couple of people glanced at me as I arrived at the counter to look at the board. One of the nurses who sat behind the counter seemed annoyed to see me, but she seemed annoyed by everyone else, too.

OK—I’ll keep away from that one.

Mostly, they all ignored me and went about their work of making notes in patient charts and talking on the phones. The group exuded a general air of weariness, but a few of the faces were cheerful and I could make out at least one friendly conversation. I tried to figure out which person was going to blow the whistle on me as the unqualified interloper. I nodded and smiled at a few residents in scrubs and white coats, got a look at the white board, and headed off toward my patient’s room.

Nice job, Dr. Hasenyager…you kept cool, blended in. That was pretty slick.

My tiny self-satisfied smile evaporated when I realized I had set out in the wrong direction and would need to double back in order to get to my patient’s room.

Shit.

I started losing my composure, tearing up slightly as I did a U-turn in the hallway and walked as fast as I could past the nurses’ station—my eyes fixed straight ahead and my leather folder held defensively across my chest. Those last few seconds before arriving at my patient’s room expanded as fear warped my sense of time.

I don’t think I can pull this off–of course I can pull this off. What if she (the patient) is mean? What if she won’t talk to me? How do I introduce myself? Dr. Hasenyager? Jennifer? Dr. Jennifer? Student Doctor Hasenyager? What if someone asks me a question…a MEDICAL question? Oh my God, I have no idea what I’m doing.

I watched my hand knock on the cheap hospital room door.

Just play the part and hope for the best.

I walked in, smiled, took a deep breath, and started acting. I don’t remember a lot about our interview. I know that I asked the questions I was supposed to ask and that I managed to take notes while simultaneously maintaining the impression I was a confident professional. I remember my patient was a very sweet and chatty woman in her 70’s and that her husband was also in the room. They both seemed to believe I was a doctor and I knew what I was doing. My patient was scared about loosing her independence at home and didn’t know if her husband could manage to take care of her. She didn’t come out and say those things to me, but I could tell from the way she answered my questions. Her husband had no idea she was worried. I was completely unaware that my knack for picking up unspoken information was both a gift and vulnerability. Ignoring my instincts, I focused on the data—the black and white answers to the questions on my list. I spent about thirty minutes talking to them, firmly shook their hands goodbye, and escaped back into the hallway.

As I walked back toward the student lounge, I reflected on my performance. No one seemed to notice how clueless and scared I was. As long as I played the part and concealed myself, I was passing as a doctor.

I can fool them all with this white coat on–amazing.

In that long hallway, I noticed the doctors swung their clipboards and folders loosely by their sides rather than holding them tightly to their chests as a school girl would hold her books. I looked down at my tightly-held folder and let it swing by my side.

Hands in Anatomy Lab

As the first year went by, we all settled into the routine of our classes and our new roles as physicians in training. The sharp creases in our new white coats relaxed, and so did we. There were many classes—biochemistry, immunology, histology, physiology—but anatomy remained the symbolic and literal engine of our transformation from college kids to physicians. At about the mid-point of our six-month long gross anatomy course, the time came to dissect our cadaver’s hands. Until that time, his hands had remained wrapped in cloth and plastic baggies. Our instructors had explained to us early on that the tissues of the fingers (and toes) were very thin and delicate and would easily deteriorate if they were exposed to air. We were, therefore, asked to leave the hands and feet wrapped in the preservative-soaked cloths until the time came to do the dissection.

On the day of the hand dissection, my lab team gathered around our cadaver and paused. I felt nervous, almost reluctant, to unwrap his hands. I think my three teammates did, too. We didn’t talk about being nervous and the pause was brief. Then two of us began to unwrap—one on each side. I clearly remember being one of the unwrappers, though I’m not sure which hand I worked on. As I removed layers of damp cloth, I became increasingly tense.

I don’t like this. How did I end up doing this job?

I felt a vague dread as the last layers came off and I held his bare hand in mine.

His nails were neatly trimmed. His fingers were long and thin. There were the usual age spots one would expect on a 70-year-old person’s hands, but they were otherwise very nice looking hands. I turned his hand back and forth.

What did he do?

I saw images of him working at a cheap metal office desk with a goose-neck lamp.

Accountant at a small company?

I saw him holding a book in a comfortable chair, reading for pleasure. I saw him holding his wife’s hand as he spent his last few days in a hospital. I saw him petting his dog.

He was kind.

Even though I had laid my hands on every one of his internal organs, traced his blood vessels and nerves through his body, and discovered that he’d had a hip replacement, until that moment, I hadn’t felt connected to him as a living human being. Now, I was connected. My breath caught. I wanted to show my gratitude by acknowledging his...personhood.

Oh, you dear man. Thank you. Thank you for your gift to me.

Here was a person whose name and life I would never know, yet I knew all about him. I knew things about him that none of his loved ones could ever know, like the way his heart looked on the inside. I knew him. And at that moment I could not bring myself to destroy his hand. I wondered if he was grumpy when he woke up in the morning until he had his coffee, or if he was an early riser who relished the quiet of the dawn. I wondered if he’d had a good life, filled with love and satisfaction—I hoped so. I wondered why he’d chosen to donate his body for our education. Despite knowing that it was his wish to give his body in this way, I still held his hand, unwilling to deconstruct it.

All of those thoughts and feelings must have flashed by quickly because none of my team members seemed aware I was hesitating to begin the dissection. They were busy reviewing the lab manual and arranging instruments. His other hand had also been unwrapped.

How can I do this to him?

I felt deep regret as I set down his hand and tried to focus on the lesson plan. My teammate read from the manual about where the first incision was to be made.

There is no way I’m making that incision.

The internal mutiny was gaining momentum, and I tried to reason with myself.

What’s wrong with you? You’ve been doing anatomy for months now. Hands are just another body part. Get a grip.

Time was running out—the team was going to notice my squeamishness very soon.

They won’t understand this. Freezing up over a dead grandmother is one thing, but a sudden personal relationship with your cadaver is over the line.

I was looking down at the lab manual, pretending to study it as I silently scrambled to get control of my powerful aversion. Staring at the hand diagrams on the white page, the images began to blur out, leaving just the whiteness. There was something soothing in that cool, white space. In my desperation to conceal my distress from my teammates, I concentrated intently on the white, and it began to seem that I was entering that white space, becoming surrounded by it. The calming whiteness contained a beautiful silence, as if it insulated me from the paralyzing clamor of my emotional reaction.

That’s better. Stay here.

I took on the calm of the white room that had formed around me. I kept my eyes on the lab book rather than on his hands until I was sure that the first few incisions had been made by someone else. When I finally looked up from the book, the white room faded from my vision, but its calming effect lingered. My pain at dissecting his hands wasn’t gone, but it seemed much farther away. I picked up the instruments and did my share of the work. My stomach hurt a little, but my head was clear and my hands were steady. Most importantly, no one knew that I’d struggled at all that day.