1.

Below a ridge above Little Hell Roaring Creek, I lead Greg off the trail. To our south, glaciations and alpine erosions have carved up steep, knife-edged ridges, wrinkled, craggy peaks, and deep, cereal-bowl cirques yet littered with winter’s leftovers. I want to show him the view from here, but we still need to bushwhack higher.

This should at least give him a good taste, I tell myself—knowing that even when we do reach the ridge, we won’t yet see the looking-glass lakes and speckled alpine meadows from last summer. For now, they remain untouched since last fall, squished into the cold, stubborn fists of this range. By midsummer, the sun, wind, and water will have meted out from its cracked and calloused palms killer fly-fishing hideouts—lakes blazing with cutthroat trout salmon-orange from an endless sea of zooplankton.

We stop at mid-slope for air and I reach around my pack for water. The bottle is stashed in a handy outside pocket—one usually reserved for my radio. Today, though, the dead weight of a speaker, wires, and two accompanying battery packs lay deep beneath the driver’s seat in the greeny rig three miles back at Spanish Creek. Minimizing pack load is working smarter, not harder, I tell myself.

That’s Indian Ridge, I say, pointing to a high, white crease between us and Gallatin Peak, the highest mountain around. Several peaks not far from here top 11,000 feet, I add.

Where are we? asks Greg.

The northeast boundary of the Spanish Peaks, I say.

How far to the Lee Metcalf Wilderness?

It’s our first day, I remind myself. He’s winded, needs water, and still hasn’t found his bearings yet. While the ten-mile day-hike from the greeny at Spanish, over the crest, down Logger Creek to Greg’s rig parked on the Gallatin seems like a good test run for our plan, I am still sketchy of the dynamics: me, the sojourning undergrad/lone wilderness ranger leading through the backcountry, the satirist, singer, poet, painter, English professor, and now my fellow fishing addict, and wilderness volunteer, Greg Keeler.

You’re standing in it, I tell him removing my ball cap, content with just carrying it the rest of the way up. The Spanish Peaks Unit of the Lee Metcalf, I emphasize.

The slope’s tall sage brush and heartleaf arnica tickle my calves, reaffirming why I always wear cruising shorts in the backcountry. The ridge at last gives yields a 360-degree panorama, reminding me again of how enveloped we are. Adjacent to the north, the prairie and pines wind together across Ted Turners’ Flying-D Ranch, home for some 3,000 head of free-roaming bison.

The slope’s tall sage brush and heartleaf arnica tickle my calves, reaffirming why I always wear cruising shorts in the backcountry. The ridge at last gives yields a 360-degree panorama, reminding me again of how enveloped we are. Adjacent to the north, the prairie and pines wind together across Ted Turners’ Flying-D Ranch, home for some 3,000 head of free-roaming bison.

Sprawling over twice the size of the wilderness, the ranch buffers us from a heavily cultivated maze of bone-colored stains and shattered mirror reflections beyond. Twenty-five miles north, the Bozeman buzz is nearly audible. Named after a man who in the 1860s left his wife and children in Colorado to mine the miners here, the town is now at full-tilt mining the tourists.

The Valley of Flowers, Greg says.

Flowers?

The English translation for the name the Blackfeet gave the valley. He speaks with the same humble tone he does in his Regional Literature or Poetry classes. Before Bozeman, Bridger, Lewis and Clark, or any of the rest, pausing in thought, he waves his arm across our view; the valley was a common hunting ground that the tribes agreed belonged to no one.

And when Clark was headed back, I add, he re-christened it after the U.S. Treasurer. Isn’t that how it went?

Yep, Greg drops his pack. How the West went.

Gallatin just sounded manlier, I guess. I am goading him on and don’t even know it.

He smiles into the wind and digs into his repertoire. We’re men among men and manly men, he sings. Yes, manly men are we / We’re men among manly men among manly / Manly men are we.

Unbeknownst to me or the birds, I’ve surfaced another character from one of his satirical western melodramas. In a galloping cadence, he belts out to the hills, swinging his arms, elbows bent at his chest, hands slightly fisted.

We’ll drive out West on a buffalo hunt / In a venture bold and daring. / We’ll shoot one again and again and again / While the others stand there staring. / While the others stand there staring.

I laugh and clap in rhythm.

We’re men among men and manly men. / Yes, manly men are we. / We’re men among manly men among manly / Manly men are we.

When he finishes, his arms and hands relax as he smiles as if for the first time in a week he’s finally taken a shit. He shakes his head and marvels. Such contrast, he says. The one naming the place after its aesthetic qualities, the other after, he pauses again looking down at his zipper, well...

Manly men, we say in unison.

I hand him my monocular and face us northeast, to the Bridgers—a blue, snowcapped range caressing the opposite side of Gallatin Valley, its southern-most foot emblazoned with whitewashed rocks forming a giant capital M above a smaller rock-formed B. He looks beyond the range, farther to the northeast.

Must be the Crazies on the other side of the Bridgers, he says.

It’s working, I figure. He now has his bead. Yes, the Crazies, I say. Named after, well....

Go ahead. You can say it, says Greg looking around us. I think we’re the only ones up here.

A woman, right? Some obscure, nameless crazy woman, right?

Yep, says Greg, busting into a crotchety western drawl. Retreated up there after going insane from her family being killed off by Injuns.

Don’t know as I could blame her, I try playing along.

Blame her? Bah! He puffs his chest and throws from his hands more air to the wind. She was a woman. Her name just wasn’t important. It was how she behaved, damn it.

At last I am struck by what makes my professor and volunteer tick; how satire courses through him like spawning steelhead up raucous rivers, compelling him to mock even the sun, were it to point out the painfully obvious and oblivious.

A brisk, spring wind slaps our faces. I keep to myself how this place brings me back to my bedrock: wrestling trout up high on Triangle Lake, my two brothers, my cousin, and me baking our adolescence in gleaming snowmelt and limiting out in under an hour; the snow bar that Dad, as president of the Red Lodge Chamber of Commerce, orchestrated each July atop the switchbacks on Beartooth Highway, his crew pouring free beer and well drinks to everyone headed into town; the rainy, snowy, miserable thirty-two mile trail from Cook City to East Rosebud Lake—the hitch that gave me my first muddy exposure to my own spirituality, while slogging along behind my sister and a dozen other teens from her evangelical church youth group.

Greg looks west through the monocular to rolling hills covered in timber.

Cowboy Heaven, I say.

Right.

I dig out the topo, tracing for him a favorite horse riding trail for locals, how it bounces and bumps in and out of Alder Creek, Placer Creek, Willow Swamp, and Cherry Creek—four fingers splayed across the foothills like a giant hand—before dropping down into the Beartrap on the Madison.

Greg climbs on his imaginary pony and cloppity-clops westward like Gene Autry, crowing, boy-cow, boy-cow, boy-cow, boy…

To the south again, I study access across snow up top, the way the peaks play shadow tag bluffing a ruse against all that fritters away its back side. I remember peeking over that crest last summer, watching picture-perfect Lone Mountain watch the onslaught between us: Big Sky and its multi-million dollar homes, hotels, high-speed trams, ski lodges, golf courses, swimming pools, and cozy coffee bars. One endless hunger feeding another, I figure: aggressive logging and untold more development parsing the scant swatch between the bitter edge of town and designated wilderness. The thin window dividing exploitation from tranquility—everything that is from everything that once was—grows thinner by the day.

We headed for that snow today? Greg asks.

Just to the edge, I say swigging water.

To the map again, I show how a couple miles from here the 401 splits with the south leg winding over Indian Ridge then down below Gallatin Peak along the shore of Thompson Lake—a route I plan to do a couple times later this summer. I then point out the east leg, where we will end up today. The line I trace drops down Logger Creek to the Gallatin where Greg parked this morning before climbing into the greeny, then along our road to Spanish Creek. I point back to the trail junction up top. Most years, I say, all three trails are blocked by snow through mid-June or July.

Only to see it fly again by when? Late August, mid-September?

Even after it does melt, I continue, some will wish it hadn’t for how rare drinking water is up there.

No drankin springs, huh? His crotchety drawl has resurfaced

Nope, I tell him. Just a desolate, wind-swept ridge. And it’s not just the lack of water up there. No fire wood, either, the way it stays so far above timberline.

Which means what for the friendly wilderness ranger? he asks.

No rock fire rings, I say. Which means no tin cans, no freeze-dried turkey tetrazzini wrappers, no tiny shards of foil littering the ridge, and no alpine shorelines eternally strewn with ass wipe.

I’m glad you’re not bitter about it, he laughs.

Still doesn’t stop hunters, I say. Looking for elk, deer, bear, moose, sheep, whatever tag they can fill. And having no tags won’t even stop some. Why would it? They’ll still load the mules down with fuel and water and tents and rifles and stoves and beds and coolers and beer and...The sentence nearly turns me blue as I gasp for air. All of it, just to be here.

2.

We recline in the shade along the trail for lunch close to the Indian Ridge/Logger Creek junction. Greg’s white plastic caskets from the morning’s stop at Four Corners have been emptied, the white bread sandwiches devoured along with most of the Cheetos. My dehydrated mangos, apples, and gorp that I made yesterday are nearly gone, as well; deep smoky, salty venison jerky yet lingers through my teeth.

I lay my head against the mountain and look up to our cerulean ceiling through the few trees remaining at timberline. A lone baby mountain grouse stranded on a branch, I discover, has been doing surveillance over our entire meal.

I put on my leather gloves and slowly stand. Someone needs poked, I say quietly.

Greg stops crunching his Cheetos and looks at me bewildered, unsure whether he understands.

I reach up into the tree’s bowels, but can’t quite touch the silent cheeper.

Jesus, says Greg. What the hell is that?

I pick up my shovel and hold it down by the blade, gently rubbing the tip of the handle along the grouse’s tummy. Pokey, pokey, I say in a cartoonish Mickey Mouse falsetto. Gonna poke me a baby grousey.

The cheeper clucks and scoots further out on the branch.

Watch out, says Greg finding a similar falsetto. Gonna learn how to fly. Oh boy. Here we go. Where’s my next branchy?

I nudge the tummy again. Pokey, pokey.

Finally fed up, the cheeper musters a flight to another tree down the draw. The flapping wings spook out two more cheepers, which we also hadn’t noticed.

Is this what you brought me up here for?

Like waking from a fuzzy dream, his line brings me back to trail. I gather my containers and schlep on my pack, or it schleps me back on.

3.

The sign which I hung on a lodgepole last summer still faces north. It reads:

Trail 401

Indian Ridge (an arrow points ahead)

Spanish Creek Campground (another arrow points right)

On the tree’s opposite side, a sign facing south reads:

Logger Creek (an arrow points ahead)

The signs are cleanly routered and hand-painted in the traditional Forest Service Tudor Brown with sunny, yellow lettering. On the north-facing sign, however, beneath the words Spanish Creek, someone wanting to pinpoint themselves has scrawled with a pocket knife 6 mi. The distance is being disputed, however, by the one who came later correcting the error with his/her own pocket knife, scribbling out the first distance and replacing it with 4.5 mi.

Why doesn’t the Forest Service just put the distance on these signs? Isn’t that kind of important?

They used to put distances on them, I say, and I asked the same question the first time I saw that sign down at the District. I rub my fingers over the scrawled distances. But the scribbles sort of answer the question for me. One person’s four-point-five is another person’s six, or eight, maybe. Depends.

On what?

Context, I suppose. And contents. How heavy is your pack? How much water did you bring? Have you slogged through the horse sewer like us? I point to a pile of horse shit next to the sign tree. Or did you sit on your ass the whole way and listen to your horse fart about how far back here he’s lugging you?

Greg leans against the sign tree, digs in his pack for more water, and belts out another song. I’m proud I’m a man / and I’m proud I’m right handed. I’m proud I was born well endowed.

I recognize this one. He once sang it to me on a fishing trip up Paradise Valley on the Yellowstone.

I’m proud of my Ford / and my team when they’ve scored / and I’m proud I can drive when I’m plowed. I’m proud of George Bush, / and I’m proud of my tush, and I’m proud I can fart really loud. And I’m proud to be proud to be proud to be proud to be proud to be proud to be proud.

I pick up my shovel and continue along the ridge, fighting back tears of laughter.

I’m proud to be white, / and I’m proud that I’m right, / and I’m proud I’m obnoxious and loud.

He’s not stopping and neither am I, my heavy boots pounding the flat top ridge, thankful for how he keeps away bears.

I’m proud of my gun / and that we’re number one, / and proud I ain’t part of the crowd. / I’m proud of my flag, and I’m proud I’m no fag / and I’m proud of my gut when I’ve chowed. / And I’m proud to be proud to be proud to be proud to be proud to be proud to be proud.

A short gust of wind applauds Greg through the trees. I try giving the carvers the benefit of my doubt, telling myself that some only break out the knife under the pretext of wanting to help the next traveler. Yet, the next person’s desire to know distance has equaled his own sacred search, so he scrawls his own correction.

I’m proud I’m a Christian, he belts out again. And proud I don’t question, the reasons I have to be proud. / Yes, I’m proud to be proud to be proud to be / proud to be proud to be proud to be proud.

I suppose it kind of enhances the whole wilderness experience, I say.

What, my singing?

That, too. The lack of distance on the signs, I mean. I point back to the junction. Some people just breathe easier when they know how far away home is.

We stop above the timber and krummholz as the trail peters out into a drift of lingering snow atop the green-yellow tundra of Indian Ridge. I break out the map, pinpointing again our current position.

If we were going over the ridge today, Greg asks, how would we know where the trail is in all this snow? Does it follow those piles of rock, somehow?

The rock piles are meant to be waypoints across the ridge, I say. Allegedly, anyway. Most folks call them cairns.

What do you call them? asks Greg.

Stone temples, for how they can hold sacred directions, allegedly—directions on where we think we have been, where we think we are going,

Why allegedly? he asks.

Because, I explain. One day late last spring with thick fog quickly rolling I found myself allegedly following the stone temples across this ridge. One by one they led me to a crumbling cliff peering over a field of sharp, angular boulders that looked more like giant hunting knives, like it was the end of the trail, or something. But there is no end to this trail. It just parallels the top of the ridge for a mile or so then drops down switchbacks over the other side.

You don’t mean...?

No, I wasn’t lost, I interrupt. Like a real manly man, I was just temporarily disoriented.

Allegedly, he says shaking his head.

The moral, I tell him: in heavy fog, stone temples are to be trusted no further than one can hurl them, as I did shooting them down the cliffs among the giant hunting knives.

4.

We back-track toward the scribbled junction sign, both of us silent as the view from the ridge yields glimpses of a myrtle vein etching the bottom of the canyon: the Gallatin River and its busy ribbon of highway mimicking it’s every turn. We are both silent as the thought of the stone temples takes me back two weeks ago when I last visited the bottom of Logger Creek:

After a morning of clearing trail up to the junction, I stood alone in the bottom of the drainage where the trail closely followed the creek; the thick understory climbing both sides of the steep draw. I stared at a stone temple piled atop a three-foot stump fifteen feet off the trail. Sprawling beneath the rock pile was a three-foot square, candy-apple red, shag carpet remnant. Why hadn’t I spotted this on my way up that morning?

Maybe it’s the playful work of imaginative children, I thought, but who would’ve cut the tree leaving that much stump? It certainly is no stone temple for cross country skiers or hikers as the trail (in winter or summer) is clearly discerned through the drainage. A castle, I decided, for a warlord’s retreat. Or an outpost for the brave, young prince conquering the drainage during a woodsy picnic with Mother and Father.

With my shovel firmly in hand, I loathed dismantling a child’s imagined world. Yet, because it sat on federal land and inside a wilderness boundary, I was compelled to consider the carpet trash that needed to be removed.

I thrashed away at the stacked rocks, pelting the grass and shrubs. I dropped my pack and stuffed the carpet in another black hole—a term I use for the black trash bags that I always carry with me. My peripheral view caught a powder-white object farther off the trail. It looked to be couched in a small grotto behind thick shrubs thirty yards away. Another castle, perhaps? An entire kingdom of warlords?

I walked the shovel and black hole down a spur leading to the grotto. Half-way there, I looked back at my pack next to the massive stump. If this was child’s play, I thought, why didn’t the parents clean up the mess? I looked to the grotto again. A massive dope stash, maybe? A pile of money from a Belgrade robbery? I could feel my eyebrows raise at all the possibilities.

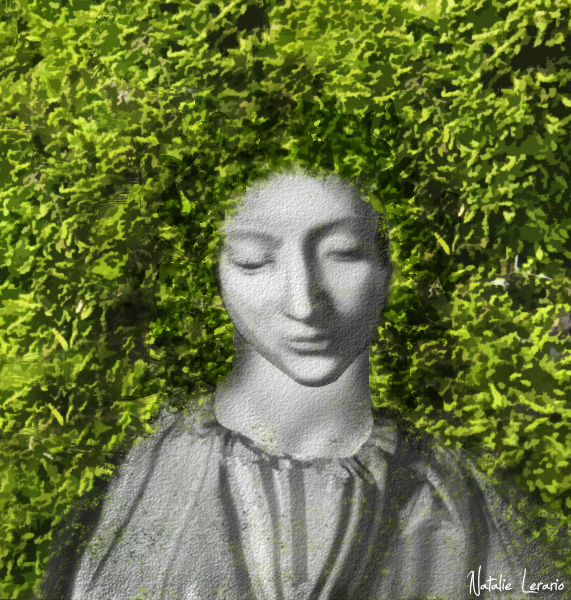

Behind the shrubs, I stood admiring how the base of the mountain met the cool valley floor in a majestic mossy overhang. The boulders were speckled with tiny green and yellow mosses, small blond and rust-brown rocks, and orange and grayish-blue lichens. A small seep dribbled down the overhang onto a deep maroon rock—a sculpture in progress. The smell was rich and full of life, like a freshly tilled garden.

My eyes wandered to the powder-white object I saw from the trail. Could it be? Yes, it was. Mary. THE Mary, in all her six-inch plastic virgin beauty, with arms open wide to bless the grotto’s parishioners. And there above her sailed plastic angels and cherubs watching over the sanctuary from tiny rock balconies.

Below and to her left, a shaded crevice propped up a hefty plastic crucifix, as a plastic Saint Someone, straddling more green and yellow moss, prayed in sacred silence. As a firm foundation, a large flat kneeling rock was arranged in the mud and dirt at the grotto’s base.

Should I be in awe and reverential, or distant and professional? I wanted to respect places of worship, but part of my job was to clean up the wild so that others—regardless of their ethos—could also freely enjoy it, however they saw fit.

I plopped my butt on the kneeling rock and tried to listen. The only thing that came to mind was how, in this visitor’s sacred quest, he or she had become an aberration in the grotto. While the carpet, stacked rocks, and plastic icons were all waypoints to a personal spiritual connection, I was aghast at how, with all the beauty behind theses shrubs, why anyone needed any of these items to attain any level of spirituality. In my haste to make it back to town, I cast the items with the molding shag carpet deep in the black hole and left the grotto.

Down at the greeny on the Gallatin, I tossed the black hole on the cab floor where it could stay in my peripheral view for the lone thirty-minute ride back to the district office. While I’ve never had an affinity for Catholicism, this went far beyond Protestant apologetics, I told myself. I congratulated myself for doing the right thing. All of that didn’t belong in that grotto anymore than my ass wipe belonged strewn along an alpine shoreline, no matter how religious I was.

I drove out the canyon sulking in silence, keeping the radio off for a change. But like a radio not quite tuned to a transmitted signal, the black hole on the cab floor was saying something that I could not make out through the white noise of my emotional frenzy. When the plastic icons finally thumped the dumpster abyss there in the district lot, I dusted off my hands, happy that my day was done.

5.

As Greg and I come back into thick timber at the top of Logger Creek, the slope is steep, the trail tread deep where the gathered water forms a gut, eroding away the switchbacks. As the haunted grotto draws nearer, I hope against hope that I do not have to share my experience down there with my professor-turned-volunteer. Why risk spooking him off?

Looks like a good place for a water bar, I say, the way everything drains down the center of the tread right here. I plant my shovel, peel off my pack, and kneel to un-strap the buck saw. Pick out a spot free of rocks and roots where the water can run off the trail. I’ll cut a freshly downed log to size.

Greg drops his pack and grabs his shovel again. Gorgo go find good spot, he says.

Gorgo, I laugh inside. The name somehow fits. His generous spirit has allowed me to call him a new name—one that sounds like he is my slave. Not that either of us truly see it that way, but, in the awkwardness of having my mentor as a volunteer, this somehow works. Gorgo it is, then. Off into the timber I scour the blow down and snow kill for a freshly fallen log no less than ten inches DBH (diameter at breast height).

With the log cut, I strip away its bark and shoulder it back to Gorgo’s chosen spot. Good, Gorgo. Now, carve out a basin and below the trench and we’ll angle the log about sixty degrees off the trail. I draw a line in the tread with my shovel blade. Make a trench here and bury the log down to here, I say, pointing to the log’s lower third.

Gorgo digs, he says, stomping his heal to the shovel.

I unhitch the bow saw from his pack and search for fresh, strong branches slightly thicker than my shovel handle. I cut them to the length of my forearm, sharpen their tips with my knife, and find a loose rock the size of my boot. The high, sharp scent of freshly peeled bark sings through my nostrils.

Back at the water bar, I pound in the branches, wedging them tight against the log, pinning the work into the trail, solid against future boot kicks and horse shoe knocks. Gorgo packs in dirt and small rocks, shoveling out the basin above.

Your first water bar, Gorgo. Way to go!

Thanks. Gorgo likes. He picks up the bow saw and secures it again to his pack.

What might now be waiting at the coming grotto still does not relent. With our packs again hugging our shoulders, my knees twinge at the steepness ahead. I slosh down three ibuprofens from the small pill box in my front pocket. You lead now, I tell Gorgo. Just kick off the trail sticks and larger rocks that could cause a hiker to stumble.

Gorgo copies.

6.

He stops in the flat bottom of Logger Creek. My t-shirt is drenched with sweat and I can barely hear from our quick drop in elevation. The pills for my knees seemed to have worked well, but my mouth is parched again. As we both reach for water, I look up from the trail to a narrow blue above. The trees still move through my tunneled vision, sweeping the canyon down to the river.

My heart rattles a few beats ahead when I realize where we have stopped: just forty yards up from the stone temple I tore down two weeks prior. The pile of rocks is atop the same anomalous tree stump. This time, for better or worse, it is without the tacky shag carpet. I cannot help but looking for the spur trail leading to the kneeling rock.

No.

What, asks Gorgo.

I pull from my pack another black hole and pick up my shovel again. Stand clear. My march to the stump ends in another thrashing of the stone temple, its rocks riddling the shrubs and grasses like fired from an M-16.

Whoa. Won’t someone need that?

I look at Gorgo and shake my head again. I didn’t want to show you this.

You put this here?

No. I tore it down the last time I was here.

Because?

Because of candy-apple shag carpet, plastic religious icons, and misguided litter bugs. I don’t know. I can’t keep it inside any longer. I tell him the whole story, clear up to dusting off my hands above the dumpster abyss.

He chuckles like a squirrel as we walk together to the grotto, where, as sure as the Pope is Catholic, another collection of plastic angels perches in the balconies above another plastic Mary, while another plastic Saint Someone kneels prayerfully beneath. This time, however, the entire diorama is eclipsed by a thirty-inch wooden crucifix straddling the mossy crag.

A white letter-sized envelope pops out from beneath the kneeling rock. I pull it free and read aloud its cursive handwritten words.

To whom it may concern, and you know who you are.

Gorgo snickers again in wonder.

I take the letter from the envelope and read it aloud, too.

Stealing is a sin and you should be ashamed of yourself. Please replace the items you stole from me. My grandmother gave them to me many years ago and they mean more to me than you will ever know. Replace them soon and no harm will be done. I pray for the salvation of your soul.

The letters are clear and legible with long, sweeping curves and curls, yet deeply penetrating the paper, as a teacher might write on a failing student’s exam.

I turn the note over to its blank back page. That’s it, I ask. No thank you? No have a blessed day? No God be with you? Just a veiled threat and a prayer for my wretched soul?

I look at the moss and wonder what to do next. As awful as I feel about committing blasphemy here again, this seeker needs to be stopped. She is an aberration in the wild, I tell myself, a non sequitur in the larger context of what it is to be in wilderness. Was she being too spiritual, or not spiritual enough? I cannot decide. All that I know is she has littered up this grotto again and my job will not allow me to stand for it.

Now you’ve done it, says Gorgo. God’s gonna have your hide. He lifts the virgin off the mosses and admires her white scarf, blue robe, and yellow sandals.

I take a Cupid-looking figure off of its balcony and, holding it by my finger tips, swish it back and forth before the grotto like a meadowlark in the wind. The angel slowly circles and descends upon Mary.

Hey, now. My Mickey Mouse falsetto from lunch with the baby grouse has returned. Watch out. Gonna pokey Miss Mary.

Gorgo chuckles. Uh, oh. Gonna pokey-poke Mary! He, too, has found his falsetto again.

The angel’s wing pricks Mary’s rib next to Gorgo’s fingers.

Oh, stop! Gorgo cries. Stop, you devilish angel!

But the angel keeps poking. Hey, hey! Pokey-POKEY, Mary. Pokey-POKEY!

Stop, you winged pervert! STOP!

Finally, Saint Someone grabs the colossal crucifix and clobbers the angel good, chipping its face and wing, as Mary forgivingly prays in silence.

With the remnants of the second episode now squashed in another black hole against my buck saw, how has the entire weight of the pack somehow doubled? Even without the radio and batteries back in the greeny, what are a few plastic action figures added to everything else I carry?