Whenever I tell people I am a writer of personal essays, they inevitably ask, “What do you write about?”

“Whatever’s happening in my life,” I answer.

My essays have run the gamut of my human experience–from the mundane and typical to the unusual and offbeat to the jolting and life-changing. I’ve written about baking Russian Tea Cakes, reacting to Marina Abramovic’s performance art, having to part with shoes in the aftermath of a bedbug invasion, finding myself a Type A worker in a Type Z workplace, and being a single woman in a coupled universe. And I’ve written extensively about the events that have rocked me to my emotional core: the murder of Richard, my boyfriend of 12 years; my bout with breast cancer; the loss of my mom’s mental faculties due to a hemorrhagic stroke and her final years in a nursing home. Surprisingly, it is these emotionally charged essays that I have found most compelling to tackle, easiest to write and most self-satisfying upon completion.

My facility and fearlessness in writing about the traumas of my life begs the question that I’ve asked myself for years: Why haven’t I ever written about the death of my father, when I was only 12 years old? Perfect fodder for a personal essay, one would think. That event, after all, consequently defined the path my life would take. It was the catalyst that transformed me from an outgoing, carefree, fun-loving kid to an introspective, serious adolescent who evolved into an adult with control and abandonment issues and a worst-case-scenario consciousness.

I can’t attribute these “missing pages” in my writing portfolio to an inability to remember my dad. He may have left this earth 50 years ago, but I can still hear his voice, remember his walk, laugh at his silly jokes, see him come through the door at night for dinner, kiss me good-bye every morning before he left for work, and sit by my bed applying ice to my forehead when I had a migraine (he too suffered from migraines, so he could empathize like no one else with my pain). He used to call me “Pookie.”

My dad had never been seriously ill in his life. Everyone assumed that he was in top physical shape because he had been an athlete in his youth. He played basketball for Syracuse University in the 1930s and, according to my Internet research, he and a fellow team member “were considered by many to be the best backcourt in Syracuse for the first half of the century.” Years after his death I heard that he had played for the Celtics before they were “The Celtics.” I haven’t been able to verify if that was so. I do, however, remember him telling me, without any malice I could detect, how he almost made the American Olympic soccer team, but the coveted slot went to a judge’s son instead of him, the son of poor Jewish immigrants from Russia.

My father’s departure from my life happened so abruptly. After blacking out in the basement one summer night, he was taken to the hospital where he suffered three heart attacks in three weeks. I never got to visit him because, unlike today, children were barred from the Intensive Care Unit. I regret that I never walked to the hospital, rushed past security and the nursing station to appear at his bedside. He would have been so surprised and happy to see me. Sometimes I forget that I was then just a kid who never expected her father would die, not the rebel I later became, who would have defied hospital rules and demanded to see her dying dad.

It is striking how easily I connect to these memories, which have remained intact and undistorted despite the passage of time. In stark contrast, I only have a few vague memories of how I actually felt when my dad died. I remember feeling emotionally stuck, numb, unable to cry even though I wanted to. I can see myself, dressed for his funeral, my head bent over the bathroom sink, feeling nauseated with knots in my stomach.

Anxiety, not grief, was my immediate and predominant emotion. As a self-conscious teenager trying to find her place in the world, I worried that since I no longer had a father, I would be different, “less than” the other kids who came from normal families with two parents. I remember expressing this self-centered anxiety to my aunt who was trying to comfort me on my devastating loss. Where was my pain, my sadness, even my anger over the loss of the father everyone knew I adored?

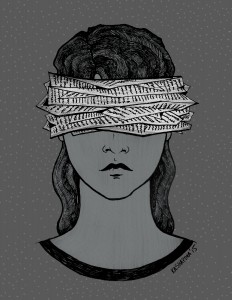

Looking back, I can see that I had shut down emotionally, coping by not coping. I resorted to denial and pretending, which helped me bury what had happened. Even at my father’s funeral, which I experienced as a surreal event, I felt disconnected, pretending that it was not really MY dad lying in that closed coffin, and dismissing the notion that I would never ever see him again.

For years afterwards, when feelings or thoughts related to my dad’s death reared their head, I quickly shifted into suppression mode, “nipping them in the bud,” so to speak. I would change the subject of my thoughts, busy myself with some activity or latch onto a vivid memory of him being alive — anything to ward off an emotional encounter with my fatherless reality.

I can still remember the discomfort I felt every year in French class, because I knew I would have to lie when our teacher would go around the room and ask each of us what our fathers did for a living. We had the same French teacher for junior and senior high school and she always began the semester with this exercise, so I was prepared. “Il est le proprietaire d’un magasin” (he is the owner of a store), I told my class, acting as if my father was still alive. I could never acknowledge, let alone express publicly, that “mon pere est mort” (my father is dead). Luckily, my schoolmates never called me on my half-truth.

My mother, my dad’s siblings and other relatives inadvertently aided and abetted my denial of his passing. My mother grieved alone, sequestering herself in her bedroom with the door shut, my sister and I careful not to disturb her. Photos of my dad disappeared; he was rarely spoken about at home or in family circles. My dead father had become a taboo subject, a family secret as if he had done something shameful by dying. If I dared refer to him, and I did so only reluctantly, a pained expression appeared on family members’ faces. Even years later, decades after my mother had remarried, that pained expression would return.

My family’s “cover-up” of my dad’s death—by not sharing their grief and their memories—made me feel excluded and further disconnected from my father. I had already become accustomed to “being out of the loop.” Even during the three weeks my father was hospitalized, I was sent away to stay with friends…a few days at Susan’s house, a few days at Leslie’s, and so on. Every time I thought I was finally going home I would be whisked away to another friend’s. I can’t remember spending a night in my own house with my mother and sister (she was too young to be sent away).

I was at Joanne’s house when my dad died. We were supposed to go to the community pool that hot summer day, but her mother told us she could not drive us because her car had broken down. My 12-year-old’s intuition knew that she was lying about the car. I later learned that she didn’t want to risk the chance of my running into someone at the pool who might say something about my father’s death. Later that day she dropped me off at my aunt and uncle’s house, where the family had gathered. As I closed the car door, she called out to me, “Honey, be brave.”

A few days after my father’s funeral, I was exiled again. Was it for a week, 10 days or two weeks? I don’t remember how long I had to stay with second cousins at the Jersey Shore until I could go home. It felt like an eternity, especially since I had to pretend as if nothing had happened. At any other time, I would have enjoyed going to the beach, riding the roller coaster, biking the boardwalk or fishing in the ocean, but my dad had just died. Why couldn’t I be left alone Instead of having to act as if I was constantly having fun? It was all very confusing. I felt like such a phony.

I must have been very adept at the “pretend game,” because I overheard an adult cousin say, “It’s hard to believe she just lost her father.” No one had a clue that I wanted and needed to grieve–not at the beach but in my own home with my mother and sister. And I was in no position to speak up for myself and force the issue!

It took me 20 years to acknowledge and feel the negative impact of being ostracized from the family fold at that emotionally critical time. Eventually, with several years of psychotherapy under my belt, I confronted my mother on her “colossal screw-up” as a parent by sending me away in such a vulnerable state. Unaware of the consequences of that action, she explained that she and the family were just doing what they thought was best by shielding me from the dark, mournful environment at home. My mother also revealed that, but for the insistence of the rabbi, my sister and I would not have attended my father’s funeral. Worried that the funeral might be too painful for us to witness, my overprotective mother thought we should stay home.

Eventually I stopped blaming my family, especially my mother, for not allowing me to properly mourn my dad’s passing. I have come to recognize and accept that my “untherapized,” unenlightened family did what they thought right under the circumstances. After all, they were also grieving, using what limited emotional resources they had available. No roadmap or manual existed for them on how to survive my father’s sudden, untimely death. We were all stumbling in the dark, uncharted territory of grief.

I’ve also come to see that given these factors, coupled with my young age and lack of emotional maturity, I was not equipped to process my father’s death. Through the passage of time, therapy and spiritual work, and life experience, I have resolved some aspects of this trauma; my misplaced anger at my father for abandoning me has been a huge issue. However, unlike the murder of my boyfriend Richard which I confronted head-on with all the emotional intensity I could muster, my dad’s death still feels like a gaping wound that never closes and heals.

When I recently confided in a close friend that I was going to write about this psychic wound, she observed, “You know, in all the years I’ve known you [25 years], you’ve never talked about your father.” The truth in her words hit a nerve. I had to admit that I have always been reticent about my father with everyone. Even today, in keeping with family tradition, my sister and I rarely mention “Daddy”; if we do, it’s only in a passing comment.

I now realize that, by having resorted to denial, pretending, avoidance and silence to self-protect and suppress the painful reality of his death I had exiled my dad to a dark corner of my past where I have kept him all these many years.

My conundrum had been: Why haven’t I ever written about my father? Maybe I should have been asking: As a loving daughter and a writer, am I willing and courageous enough to embrace his memory and invite him back into my life?