“So this is your first time out of China?” asked the secretary. I had just arrived at University of Leicester in Britain as a visiting scholar. It was early October, 1991.

“So this is your first time out of China?” asked the secretary. I had just arrived at University of Leicester in Britain as a visiting scholar. It was early October, 1991.

“Yes.”

“You must be homesick.”

“I really, really miss my son!”

“You left him home?”

The look on the secretary’s face made me uncomfortable.

“How old is he?”

“One year and eight months . . . 25 days.”

“Jesus Christ! He’s still a baby!” The vector of her eyes shot at me like a dagger, her mouth wide open, her eyebrows knitting, her accusing tone sharp.

My heart convulsed. I could see my baby son Dai bursting into a loud cry, one week before I left for Britain, stamping his feet wildly, his eyes frantically searching for me. It was his first day in the kindergarten on the Sun Yat-sen University campus where I worked.

“How often will you go home to see him?”

“One year later at the end of my time here.” My grant was so small that going home in the middle of my research period was a foreign concept.

The accusing look in the secretary’s eyes became sympathetic. “Oh, I feel so sorry for you!”

* * *

By the time I was back, Dai had turned two and nine months old, a fluent speaker of Cantonese and Mandarin. He was two babies away from the one I left.

“How come you can speak?” I marveled.

Dai gave me a what-are-you-talking-about look.

I never knew how much I missed in that year. In fact, I refused to know, to avoid further heartache. In the same way, he would not know how common it was for parents to leave their babies behind to study abroad. In the early days of China’s reforms and opening in the 1980s and 1990s, everyone was hungry for knowledge. When studying overseas was not affordable for everyone I knew, going on a government grant was too good an opportunity to give up.

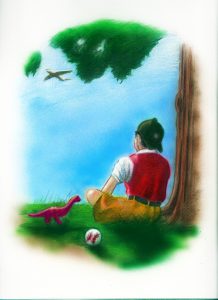

On the day I got home, it did not take much for Dai to warm up to me. My mother, who had been taking care of him, smiled and cried as he said in my arms, “Good-bye, Grandma, come and visit any time.” She had shown him my pictures every day, telling him that I went to Britain by plane and that, with each passing day, I would be one day closer to home.

Since then, every time a plane flew over, Dai would go out to the yard, jump up and down in time to “Mommy, Mommy, Mommy . . .”, head held high up, hands reaching upward.

But when bedtime came, Dai began to feel differently. He began crying for Grandma. I had to call her.

“Seeing him so attached to you is great, but it made me think I wasn’t so important to him after all,” my mother’s voice came through with relief.

It turned out that Dai did not want to be with Grandma without me. He wanted us all around him. He ranked us in the following order: Mommy, Daddy, and Grandma. This flattered me and made me feel insecure at the same time. What had I done to deserve this? For the first week, I kept asking him to rank us. He never hesitated to put me in the first place, while his dad and grandma’s rankings changed alternatively. I asked him about the ranking criterion. He gave me a look philosophical for his age:

“This week, Mommy is No. one. Next week Daddy is No. one. Next next week Grandma is No. one! Next next next week will be Mommy again!”

So he knew what he was talking about. Although my husband Jigang and I had been studying and working away from home, he recognized our importance. Or maybe approved of our absence because of whatever reasons he found for us.

* * *

I had to leave Dai again when he was four years and eight months old. My job of teaching English to people who were going to study abroad made me feel that my language skills would not take me too far. I decided to go to the United States to study human geography in 1994. This time, I felt less guilty for leaving Dai behind, as I planned for the family to go to my commencement. I would also call more often and would go home once a year.

Every time I called, Dai came to the phone to say hello.

“If something is half apple and half pear, what is it?” he asked one day.

“An apple pear.”

“Wow, how come you know?”

I could see him smiling, showing his baby teeth that were naturally straight. It brought tears to my eyes. How many moments like that had I deprived him of? I could only take comfort in writing essays on life around me. It was something I wanted to do but never had the nerve to. I wrote three pieces about him and eventually ended up writing a collection of his stories before he was 10 years old.

Jigang was touched by the stories. He had either forgotten or had not paid attention to some of the details I recorded. But how could I afford not to remember the details, when I had missed so many?

* * *

I went home for the summer in 1995, with Professor Smith who needed help with some interviews. When we finished all the work, he offered to take Dai to the zoo so that I could spend some time with Jigang.

I set to teach Dai a few words of English so that the two could communicate a little. Dai learned conscientiously for a few minutes: monkey, lion, tiger . . .

“But this is not right! Why do I have to learn English? Why can’t he learn Chinese?” The five-year-old asked.

“Because . . . because English is easier than Chinese.”

“Isn’t he a professor? He should know better about learning than many people!”

That put an end to the session.

Late next afternoon, Professor Smith came back with Dai a few steps behind him.

“How did it go?”

“Well, he kept a safe distance ahead, looking back every now and then to make sure I was following.”

“You didn’t talk at all?”

“Except when I suggested going to McDonald’s. He beamed and demanded big Mac and coke before I even asked.”

I asked Dai why he did not talk with the professor.

“Why would I bother? He won’t understand anyway!” he gave me an are-you-nuts look.

Shortly after that, a Canadian friend of mine, Don, came to visit. Around the time he was due to arrive, I had to go out for 10 minutes for something urgent. I taught Dai to say “I don’t understand English. Please call again in a little while” in case someone called and spoke English.

Don did call and Dai managed to deliver the message.

“You know, it’s hard to believe he doesn’t speak English when he did it so well,” Don told me later. He could not help asking a few questions, only to hear “I don’t understand English. Please call again in a little while” again and again.

Dai did not get it.

“Does that man understand English at all?” he asked.

* * *

One day, Dai told me on the phone that he had received a few gifts for Christmas. It was 1995 when western customs began to come to China. He had told grandma that a Santa Claus would deliver gifts to children. My mother did not give it much thought until the five-year-old came home upset the next day, wondering why Santa Claus had given gifts to his friends but not him.

“He must have had too many places to go to,” grandma suggested.

“Or perhaps he could not find where my room is,” Dai suggested, “do you think he’ll come tonight?”

As soon as she could, my mother rushed out to buy a few things. She could not bear to disappoint him, especially with me in the US and Jigang in Canada.

Dai went to bed early that night, having drawn three arrows to direct Santa Claus from the dining room to his bedroom.

The next morning heard his joyous cry over the gifts.

“He’s written to me too!” he urged Grandma to read the letter.

Dai must have felt that Santa Claus sounded familiar in advising him how to be a good boy. He asked to see the letter.

“How come the paper looks exactly like the one you use?”

“Oh, he must . . . have liked you . . . and decided . . . to write when he was here.”

* * *

I was determined to compensate Dai for my absence on the first Christmas after I returned home in 1997. He was seven and had a lot of faith in Santa Claus.

“What present do you expect for Christmas?” I asked over dinner two days before the occasion.

“I’ll tell him myself.”

“But he doesn’t understand Chinese.”

A worried look came to his eyes. His chopsticks stopped mid-air with a piece of pork.

“If you tell me what you want, I can tell him in English.”

Dai’s eyes shone. “Digital Monster!”

My heart ached a little. I had said no to this electronic pet that he had asked for several times.

“I think it best if we tell him where to get it. He doesn’t know China so well after all.” I paused to see how well he was taking the idea. He had stopped chewing, his mouth bulging with food.

“Didn’t you draw him directions two years ago? You don’t want him to come late again.”

“Tell him to go to the convenience store at the far end of the wet market. And it’s the closest and cheapest.”

I knew the store. It was 15 minutes from our home.

It worked out well for both of us. Dai rushed to my room with the toy of his dreams on Christmas Day and thanked me for my help.

A year later, Dai started to wonder about the Santa Claus myth. “You know, some of my classmates said that there’s no Santa Claus at all. We had an argument and everybody was upset.”

“What do you think?” I asked.

He fixed his eyes on my face for longer than I was comfortable. “I think there is Santa Claus if we believe in him.”

A few days after that, I turned on the TV and a clever-looking host happened to say in too loud a voice, “There’s no such a person as Santa Claus . . .”

I dashed to the TV set and turned it off. Fortunately, Dai was in his room and did not hear any of it. I wanted Santa Claus to be there for him for as long as possible. I needed to give him one magical day a year.

* * *

When Dai was 11, I started taking him overseas. I suggested going in May 2001 when we would have a one-week public holiday.

“But I want to spend time with my friends.”

The friends he referred to were the ones I wanted him to avoid. They had taken him to pubs and places to eat and play beyond their means. Their parents had money to burn and did not see that it was doing the children more harm than good.

“You can play with them some other time. We can go to Japan.” I knew he liked Japan through cartoon and games.

“I made plans with them already. Can we go later?”

“We certainly can. But I want you to learn about other countries sooner rather than later.”

We did not talk about the trip for the next month, until we were in a taxi one day. Dai asked me how to say something in English. I gave the answer.

“You know, if my English is half good as yours, I’ll go and live in the US,” the driver said.

“Why?” we asked.

“Because things are over 30 times better there than it is here,” he turned around and took a quick look at Dai. “Aren’t you tired of school? A distant relative of mine said his son hated it here. He’s now enjoying it in the US because they made school a lot of fun.”

Dai turned to me. “Is it that good?”

“I don’t think things can be measured this way. And 30 times is definitely an exaggeration. That’s why I want you to go and see for yourself. But you didn’t want to go.”

“You don’t want to go? You sure don’t know what you’re missing. I wish I had the money to take my son to see the world,” the driver sighed. “You don’t know how lucky you are, kid. You don’t know life isn’t fair, do you?”

Dai went very quiet for the rest of the ride.

“Is it too late to plan the Japan trip?” he asked as we got off the taxi.

We went on a package tour to Japan in May 2001. Our experiences and opinions about the temples, the food, and the hot springs varied but we felt the same about one department store in Tokyo.

We window-shopped through a few floors, finding things very pricey. Eventually, we decided to buy three pairs of half-priced chopsticks with fancy designs. It was five minutes before closing time. Yet the shop assistant was all smiles and asked, through gestures, whether we would like to have names engraved in each pair of chopsticks, and for free. The engraver smiled broadly, echoing the assistant by waving the little chisel in his hand.

Dai and I looked at each other: fancy having chopsticks with our own names on them! I nodded at both the shop assistant and the engraver, but also pointed to my watch. It was indicating the end of their business hours.

Between the confusing head-nodding and shaking, we understood that we were more than welcome to do the engraving. So we did.

It was 15 minutes after their time off work when the job was done. By then, two other shop assistants were there to help. One asked in halting English whether we would like to gift-wrap the chopsticks. Another fancy idea! But I was very concerned about the time. She indicated it was not a problem.

When the three individually wrapped chopsticks were presented to us, they looked lovely and exquisite. A shop assistant led our way to the elevator. As we passed one counter after another, we saw all the shop assistants stand by their counters in uniform posture: hands crossed in their front, waiting with gracious smiles for the last two customers to leave.

We were handed over to another smiling woman in the elevator.

“Wow, I can’t believe they were so attentive, especially well after the closing time,” Dai said as soon as he stepped out of the store.

“And they were so thorough! It’s hard to think of shop assistants in China gift-wrapping chopsticks, all separately,” I added.

We decided to go the next morning to see how they would open the store. We arrived at the main entrance 10 minutes early. Some employees had already formed two lines behind the glass door. They stood in disciplined silence, each wearing a warm smile, hands crossed in the front.

As we walked into the store with two other customers, the employees bowed good-morning to us. We marched forward, passing by counters where shop assistants stood like they did the day before, bowing deeply. My amazement quickly turned to embarrassment as I realized that we were making everyone bow all the way.

We talked about the experience several times during the trip, and concluded that such service-oriented management had to be one important reason why Japan had gone as far as it has.

* * *

“Why is everything so messy and dirty?” Dai asked as we rode on the highway from the airport toward home.

“’Cause you’re comparing it with Japan. This is why I wanted you to see other countries.”

Dai gave me a this-makes-sense look. Over the next few months, he would ask the same rhetorical question “What would this be like in Japan?” whenever he became critical of something.

One day a few weeks after the Japan trip, Dai came home shortly after he had gone out to play. Sitting himself down at the edge of a chair in the dining room, he put his hands between his knees, shoulders pushed upward, his back a little arched as if he were cold.

“I’m so scared,” he said, failing to keep his voice from trembling.

“What happened? Are you OK?” I never saw him so unlike himself.

“I was walking past the market and suddenly, the thought that I’d die someday hit me. I was horrified. My feet felt weak. I had to come home.”

That was an issue I could not help him with. I feared death myself, at an earlier age than him. I had been fighting the fear for over 30 years, rationalizing it, asking friends how they felt about it, consulting religious people, comparing notes with people who also had the fear, without ever finding the cure. Such fear can’t be hereditary! The sight of Dai shrinking with fear devastated me. I had to say something soothing and wise.

“Death is something we can’t worry about. It happens to everyone.”

“That’s why it’s so scary!” Dai raised his head in despair. “There’s no escape.”

“You don’t have to die yet. Neither do I. We can leave the worrying to people in their 90s. We still have all the time in the world to figure it out.”

Dai’s look became something like but-that-doesn’t-exempt-us-from-dying.

“There’re ways to extend our lives,” I reasoned, “for example, if you are good, that is, if you do what I hope you’d do, then I’ll always know you’re good, even after I die.” I had been having trouble disciplining him since he was eight. I could not help throwing this in.

Dai looked a little alert and a little relieved. The awareness of his mother starting her thing distracted him.

“Think of it this way: if you’re a good boy and will always be a good boy, then I’ll be rest assured about you and dying won’t be a problem for me. ‘Cause I know you’ll be good and I have no worries left.”

Dai’s eyes rolled, trying to work out the logic between my words and his fear.

* * *

One of the issues I had been having with Dai was he hardly came home at the time he promised to. He would come back half an hour late, one hour late. And then, outrageously late.

I did not get it. I worried myself to death. Did it mean that he had a problem with commitment? What good would he be in the job market or anywhere, if he could not keep his promise?

I had to do something major to teach him a lesson. When he came home one day, over one hour after the agreed time, I asked between my teeth just what excuse he had for that.

“I was playing ping-pong. I didn’t know the time.”

“What happened to your watch?”

“I forgot to wear it.”

“You could have checked with someone.”

“I did. But it was already late.”

“Why didn’t you check sooner?”

“I didn’t know it was that late.”

I could feel my anger rising.

“Let me have your ping-pong ball.”

“Why?”

“I’m going to smash it.’

“Why?”

“You tell me why!’

“But you paid for it.”

“Yes. But I’m not paying for the next one!” I snatched his school bag.

Dai’s mouth began to pout.

I took out the ping-pong ball.

His mouth began to twist.

I stamped on the ball.

His mouth and eyes were wide open with disbelief. He was too shocked to cry.

For a minute, I did not know where to go from there. Yet I had to bring a conclusion to the whole thing.

“I’m sorry to have done this. But I just want you to know that you can’t go on like this. How would I know that you’d take my words seriously if I don’t do something like this?”

I had calmed down as a result of the drastic action. “I wish I didn’t have to do it,” I said apologetically.

Tears streamed down Dai’s face.

He went into the kitchen after dinner. Hearing him turn on the electric stove, I tiptoed to take a look: he was boiling the flattened ping-pong ball to bring it back to life.

For the next few days, Dai came home relatively on time. Then he came home late again. I started warning him and we agreed that I could punish him any way I saw fit if he failed to discipline himself one more time.

Next time when he showed up two hours too late, we were both ready for something major.

“Are you possessed or something? Did you do this on purpose?” I tried to sound more inquisitive than angry.

“I knew I was late,” Dai said in a low voice, his eyes fixed on the floor, his hands holding nervously on to the straps of his backpack.

“So you reasoned that you might as well come back even later to make the punishment worthwhile?”

“How do you know?” Dai raised his eyelid as if I were a new-found friend.

“‘Cause I’ve been there! ‘Cause I’m your mother!” I had not thought of what to do for punishment but I should certainly make it worse than flattening a ping-pong ball that could be fixed.

“Now, I’ve got an idea. I’m going to break one of your video games.”

Dai turned pale.

“Can it be something else?”

“No. It’s meant to be painful so you’ll change for the better.”

“But you paid for them and they’re expensive.”

“I know. I’m going to break only one and I won’t replace it.”

Dai could cry any minute now.

“Now you get to choose which one you want to give up,” I said, with a morbid sense of pleasure.

“I can’t.”

“Of course you can. You could also have prevented this.”

“But it’s too late.”

“Yes, that’s why you have to pay a price. I’m paying a price too.”

Dai wiped his tears.

“I’ll pick a random one then.”

“Please don’t. Let me have a look!” he grabbed the video tape from me and read the label. “No, please, not this one.”

“I did ask you to pick one.”

He went through the small box. “I can’t do this.”

“Let me pick one and you get over the loss. It’s meant to hurt so you’ll remember.”

I picked one tape up and was ready to smash it.

Dai let out a painful cry. “You can’t break, break it, by, by, by smashing. You need to, to use scissors.”

Now smashing it would be easier than cutting it in half.

My heart missed a beat as I cut the tape. Dai cried out hard.

He was never too late for home after that.

* * *

When I suggested an overseas trip three months after the Japan one, Dai did not object. We were going on a 24-day trip to Paris, Rome, Florence, Venice, Napoli, Athens, and a few small towns in Europe.

“Is there really a God?” Dai asked after he came out of Notre Dame de Paris.

“I can’t answer that question. All I can say is that it’s a healthy thing to do. You should find out more about it.” I grew up in an environment where religion had not been encouraged. I had been to churches, temples and talked to religious people, but I just could not get into any religion like some of my friends. I envied them for their peace of mind.

“At least you won’t worry about death,” I added.

That evening, Dai talked about Grandma who took care of him for seven years. He had not talked about her since her funeral.

“I wonder how she is,” he started weeping, then sobbing.

I was pleasantly surprised and relieved. It had been five years since my mother died. He seemed to have simply let her out of his life after “she went to grandpa,” as he put it on the day she passed away. Not that he had erased her in his memory, as he would say “Grandma bought it for me,” whenever I suggested throwing away something that was too worn to use. He would say it with an icy expression, his lips set in a firm line, avoiding eye contact to make it plain that was the end of the conversation.

On the day of the funeral, Dai cried throughout the hour-long service, inconsolable in his dark outfit, shutting himself from the rest of the world. The sound of crying came in a monotonous three-syllable “ng___ng-ng” pattern, his little figure at the tender age of seven trying helplessly to part with Grandma who had been there every day of his life. I held both of his shoulders, connecting his grief to mine.

“Bye-bye Grandma,” Dai said as Jigang held him up to see Grandma for the last time. It was the every-day good-bye he would say to her. For a minute, I could hardly breathe. Did Dai just defy death by refusing to make his good-bye sound final? I could not have conveyed that any better.

“When are we going to see Grandma again?” Dai asked on our way home.

“Once a year during the Qingming Festival.”

“Qingming Festival?”

“It’s April 5, the day in the lunar calendar for mourning the dead.”

“Can we go more often, like once a week?”

“We can, but we don’t have to come here to remember Grandma. We’ll think of her every day, won’t we?”

When we got home, Dai said he wanted to give all of his 64 pieces of tigers to Grandma. They were a complete collection of toy tigers in the form of cards, through buying packs and packs of instant noodles, his most valued possession at the time.

After that came the five-year silence. I talked with a close friend several times about this, wondering whether Dai was the ungrateful type.

“Trust me, he cares about her. He just doesn’t know how to deal with the loss.”

* * *

The omnipresent cathedrals and the faith in God in Western Europe must have given Dai some comfort and hope, as he could think of an after-life for Grandma.

“Have you been missing Grandma all the time?” I asked with a teary smile.

“Y—es, I’ve been, missing, missing her, and, and wondering how she, she has been,” Dai said in a pool of tears.

“I’m sure she misses you too. I’d rather believe that God had led her to heaven. I’d rather believe that she can see us from there and knows that we miss her.”

Dai nodded in agreement in another flood of tears.

“Can you believe that a classmate of mine would have had a younger brother if his mom hadn’t had an abortion?” Dai said as we waited in the bus for the driver of our tour, outside the Siena Cathedral in Italy. He had taken out his Game Boy to play.

“I can. With the one-child-one-family policy, this is nothing unusual.”

“It’s still hard to imagine that he could have had a brother.”

“You could have had a sibling too, if not for the same policy,” these words escaped me of their free will.

Startled, Dai looked at me long and hard. “You had an abortion too?”

For a while, neither of us spoke. I looked outside the window. The Cathedral stood stately and solemnly.

The clattering of Dai’s fingers on the Game Boy became more noticeable as the silence prolonged. He held the Game Boy close to his face, pressing the keys rapidly and nervously.

He raised his right hand to wipe across his eyes now and again.

“What’s the matter?”

“Nothing,” he wiped his eyes again with his left hand.

“Are you crying?”

“No.” Yet tears streamed down faster than he could wipe them.

“Does he have a burial place?” he asked.

“No.” I did not even know whether it was a he.

“Then we can’t even visit!”

I had not thought of visiting.

“He must hate me for it.”

“No. That’s not logical. You came after it.”

“Then he must hate you!” Dai turned to me, his eyes piercing hard, as if he were doing the hating for the sibling he could have had.

That, I never thought about either. In fact, I had not allowed myself to think about it, knowing I would not be able to handle the complex feelings and issues. Dai’s grief and accusation evoked my grief and guilt.

For a silent moment, we honored the life of the unborn being that would have been part of our family, many years too late, outside the Siena Cathedral, in the faraway country of Italy.

* * *

In May 2010, Dai went to Western Europe again after having taken the course Western Civilization at the University of Pittsburgh. He sent a postcard home from the Vatican. “All is well with me. Hope our family will be here sometime.”

That was in reference to something he wrote on one pillar of the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral when he and I were there in 2001, after debating whether he should write something on it like many others had done. “DAI Fan and BAO Dai are here. Hope BAO Jigang will be here someday. If you are here, please check the following box.”

I had laughed that he probably had done too many exercises that asked for a check. I had been touched by his thought of his dad who could not make the trip.

* * *

In May 2015, Dai graduated as a history major and an architecture minor from Columbia University. It had taken him seven years to get there, having changed majors, traveled extensively to over 70 countries, had two hiatuses either to recover from hard work, or to debate what his education should be like and about.

“You know what, Mom, you probably haven’t realized what the three overseas trips in 2001 meant for me,” he said three years into his undergraduate study, ”you may not have picked those countries deliberately, but Japan, Italy, Greece, France, and Australia represent three continents. They were far too overwhelming for an eleven-year old.”

I did know one thing. The time abroad with him was most precious because we talked about things we failed to communicate at home. If not for the time in Italy, I would still be worrying about how he feels about Grandma; I would still bear the secret burden of the abortion.

“I became aware of differences. People. Cultures. Foods. Approaches to problems, and many many other things.”

These would explain why he took courses in philosophy, religion and history and took six study-abroad programs between Pittsburgh and Columbia, in spite of the same frequently asked question by all:

“What are you going to do after you graduate?”

Dai typically shrugged his shoulders, wearing a smile like he didn’t care.

“I want to be a thinker,” he told me one day, a little smile playing around his lips.

“One can think even when one has a job,” I reminded him.

“I know,” he reached out to pat me on the shoulder.

* * *

Dai is now spending one year in the US, having a great time trying to be a real estate agent in New York City, a multilingual actor for emerging film-makers, and a bar-tender if the first two fail, in addition to his long-term plan of establishing a university and to provide the best education he could think of. I could see him thrive in any of those directions, knowing the courses he had taken, his gig of playing Bruce Lee at the Hollywood Walk of Fame, etc.

I talk to him every day to find out about his progress. He has had an offer from the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at Columbia University, three major roles in three different short films, and two potential closings for two real estate deals.

I await with interest for further news.