“Poets think they are pitchers, but they are really catchers.”—Jack Spicer

If I could tell you one thing about myself, it would be that the first funeral I ever attended was for someone who I didn’t know. It was at Yankee Stadium: the old one. I went there for the first time on August 6, 1979. But this story begins on August 2nd of that same year. Sort of.

My father had just come home from work as a bus driver for the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority. His face was bathed in sweat and smiles as he entered the kitchen. My mother was chopping onions. It was the only time I can recall him coming from work without complaining about his aching back, his sore legs, or traffic on the L.I.E.

“Dry your scallion tears, Marie,” my father yelled. “We’re gonna’ see the Yankees!”

“Mmm-hmm.” My mother was not impressed. She had been trying to get my father to buy Yankee tickets as long as I could remember. The fact that my father’s bus depot was next to Shea Stadium, the old digs of the Mets, was irrelevant: ours was a Yankee house. My Grandparents, my father’s folks, lived downstairs. They had told me stories about all of the Yankee greats, especially the heroics of the Italian-American stars: Tony Lazzeri, Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzutto, and Yogi Berra. They admired the way Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Whitey Ford, and Mickey Mantle played baseball, but they adored the Italian-American Yankee stars, because they were “our DNA; a more direct part of us,” as my Grandmother once said. They were examples; living proof in pinstripes of the promise of America; that one could achieve a life of prosperity if he or she persisted and made the most of their abilities. What the Yankees are to New York, being Italian-Americans is to my family—you wear it with pride, just like both of my Grandfathers did in their military uniforms for Italia and America, in World War Two, respectively.

Although I knew of Ruth, Gehrig, Lazzeri, Ford, and Mantle, I didn’t see them play, so I feel as though I can never fully appreciate their accomplishments. I did, however, have the chance to meet Joe DiMaggio at a baseball card show in Midtown, Manhattan when I was 12 years old. I also grew up seeing Yogi Berra as a coach for the Yankees, so they mean as much to me as the players I grew up watching: Thurman Munson, Bucky Dent, Graig “Puff” Nettles, Reggie Jackson/Mr. October, Ron “Gator” Guidry, Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Goose Gossage, Willie Randolph, “Sweet Lou” Piniella, and Bobby Murcer. The names of these men are the melody of the background music of my childhood: a sonorous tarantella for the wedding reception of my memory’s dance floor.

The late 1970’s Bronx Zoo Yankee teams were compiled of a cast of boisterous, colorful, free-wheeling characters: they came to the neighborhoods and residencies of my family members from the country of Television, which made them transplants—a new wave of immigrants, just like my relatives were. The way my parents and grandparents saw it, the Yankees were Nicolettis, which made Thurman Munson our clan’s captain.

What’s more, Thurman was the first Yankees team captain since Lou Gehrig. I learned later on that Thurman was a reluctant “official” leader. He wanted his play to speak for itself, which it did. He made seven American League All-Star teams, and was the starting catcher for three of them. As the 1970 Rookie of the Year and the 1976 Most Valuable Player, he was and remains the only player to win both awards as a Yankee. Thurman was also a clutch hitter, owning a lifetime .357 batting average in postseason play, including a .529 clip in the 1976 World Series. He often played injured: he endured broken hands, separated shoulders and blows that knocked him to his knees, which were fractured on several occasions. Many of my memories are images of him staggering to get to his feet after tagging a runner out at the plate or being beaned by an opposing pitcher. Thurman was relentless. The more pain he was in, the more spectacular his performances seemed to be. His unique combination of tenacity and talent mesmerized me: Thurman was Major League Baseball’s Poet Laureate of guts and persistence; a star player who played with the urgency and intensity of any of the fans sitting in the cheap seats or watching the game on the tube at the neighborhood bar or at home. Tanti saluti.

I was also taken with Thurman’s appearance. He didn’t seem to look or carry himself like a typical baseball star: he was squat, even for a catcher, and had quite a paunch. One could make a case that he always looked out of shape. Coupled with his scraggly bearded face, he looked to me like a hairy punching bag.

Thurman and my father seemed to share a go-getting, blue-collar approach to their livelihood. I remember him scowling the eyebrows off of any pitcher who dared to shake him off, especially during games against the Boston Red Sox and the Kansas City Royals. My father wore the same expression on his face whenever a taxicab or truck tailgated his bus. Even though Thurman was a famous ballplayer, he was an everyman, just like my father, albeit an athletically gifted, feisty everyman who was as stout of heart as he was of stature: two rough and ready, family-oriented men whose professional demeanors were fostered for pursuing the diamond life for their loved ones; la dolce vita in an equally rough and ready work environment.

“Watch and learn. He hustles,” my father would say to me, his face bathed in the electric glow of televised baseball.

A prominent part of my Scorsese-esque cast of family characters is my Aunt Karen. In addition to being the wife of Uncle Michael—my father’s kid brother, she is as big of a fan of the Yankees as she is of eating and playing Pokeno. She had a crush on Thurman, to Uncle Michael’s chagrin, which he combated by calling him “Walrus Man.” Nevertheless, Uncle Michael was also a die-hard fan, especially of the 1960’s Yankee teams. Like my father, his favorite player was Joe “Pepi” Pepitone, the notorious slugger who introduced the use of the hair dryer in baseball clubhouses and wore a toupee under his cap. Pepi played First Base, like Lou Gehrig—Uncle Michael’s second favorite Yankee—did, both of whom were New York City natives: Pepi from Brooklyn, Gehrig from Manhattan. Also, like Gehrig, Pepi’s name is a strange legacy to the game of baseball and beyond. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis is also known as “Lou Gehrig’s Disease,” while “Pepitone” roughly translates into “Goof-off” in Japanese.

Uncle Michael referred to Joe Pepitone as “Pepi le Pew,” after the Looney Tunes cartoon character. According to family legend, Uncle Michael struck out Pepi with the bases loaded in a little league All-Star game. My father once said that he was never more proud of his brother than he was on that day. Uncle Michael’s assessment of his performance was succinct:

“I always liked Pepi le Pew because he stunk, especially when he faced me.”The Pepi le Pew Affair, as it has come to be known, is his favorite war story, and he’s a Vietnam Veteran. It always came up whenever he watched the Yankees with us, which was often. Regardless, my family’s interpretation of Yankee baseball telecasts was that the team had been to our house countless times. As such, Sweet Lou, Bobby Murcer and Thurman Munson were our favorite relatives and guardians: our spiritual Zios and Padrinos. We lived and died with Sweet Lou, Bobby, Thurman, and the rest of our beloved Yankees each baseball season. The Bronx was always burning in our house, perhaps never more so than it did in 1979.

After my father showed my mother the tickets, we ate dinner. The hills of my mouth were alive with the taste of homemade gnocchi. I was ecstatic, almost careless of my mother’s ladle, which had three dents in it: one from my sister Nicole’s head, one from mine, and one from my father’s. She hit Nicole and me with it during the previous Christmas Eve because we were up past our bedtime. My father was hit because he allowed it. My mother continued to serve food with the ladle, as a reminder to us of the importance of order. I took to calling it Mjolnir, after the Marvel Comics character Thor’s hammer, his trademark weapon.

After dinner, Nicole and I were in the living room. She was watching Beneath the Planet of the Apes. I was half-watching it, alternating between watching the movie and reading a dog-eared copy of The Invincible Iron Man during the commercial breaks.Nicole’s enthusiasm for the movie was loud and proud. One particular example of this stands out. I missed the end of a commercial break, but the character of General Ursus, played by James Gregory, caught my attention in the scene where he sees a statue of the Lawgiver, the Ape’s God:“He bleeds! The Lawgiver bleeds!” Aghast, the character Dr. Zaius put his hand in mouth, and Nicole flashed her world-famous-on-Teed Street-ear to ear smile. “Yes! Love it! Beneath the Planet of the Apes!”And how. I do, too, thanks to Nicole. I nodded, and resumed reading my comic. “POW! Iron Man’s cool,” Nicole said in her booming voice as she read over my shoulder.“Yeah.”“The best-dressed hero there is.”“Not really,” I said. I couldn’t help myself. I channeled my inner wise-ass. If was a Super-Hero, I would be Captain Contrary, or Dr. Different, at least in the company of my family.Nicole was onto me like the sauce on the gnocchi we had for dinner. “Not really? Whatcha’ mean, not really? Who’s better?” she asked, glaring at me like a bull charging a matador stripped of his red sash and dagger.“Wonder Woman.”“Wonder Woman? Because of Lynda Carter, right?”I was guilty as charged. “I think she makes her costume pretty.” La donna è molto bella. “Yeah, she’s hot,” Nicole said, sipping her glass of water.“I like her invisible jet. It would be cool to know how to fly a plane. I could go anywhere I wanted.”“Quiet!” my mother yelled. “Turn up the volume!” She walked into the living room on-point, a seemingly decade’s worth of concern in each step, with Mjolnir in her right hand.“Anywhere I wanted,” murmured Nicole.

The dulcet tones of a broadcast news anchorman’s practiced bass filled the room with starched-shirt confidence.

“Good evening ladies and gentlemen. We interrupt this program to bring you this special report. New York Yankees catcher and team captain Thurman Munson was killed in a plane crash earlier today.”Silence filled the house like stuffing in a burnt turkey.“Killed?” I asked no one in particular.

My mother’s concerns fell in tears and mascara down her face as the announcer continued. Thurman was an aviation aficionado, and had recently purchased a twin-engine Cessna citation jet. He had been practicing flying it anytime the Yankees had a day off. When the plane came in for a landing at the Akron-Canton, Ohio airport, it crashed short of the runway and caught fire. Canton was his hometown. There were two other passengers in the jet, both of whom survived. Thurman’s last words were, “Are you guys okay? I can’t move.”

Neither could I. It was at this point that I noticed that my father was in the room. “Holy shit,” he said quietly.

My Mother lit a Benson and Hedges cigarette. My father walked out of the living room, muttering to himself.

***

August 5th arrived like a successfully hailed taxicab on a rainy day in the city. “No singing at the table!” my mother yelled at my father, who was humming a buttery-aired version of “Under the Boardwalk” over his plate of steak and a baked potato. He was giddy, even by his standards.“So,” my father said, “It looks like our game won’t be cancelled.”My Mother was surprised. “They’re actually playing?”“Mmm-hmm,” my father said. “Should be a good one. I hate the Orioles. Too many traitors on that team.”“Traitors?” I asked.“Fuckin’ a, Joefish.”Mjolimir reared his dented head in my mother’s right hand. “Don’t you read the backs of your baseball cards?” my father asked.I wasn’t following. “Sure.”“Then you know that Jim Palmer was born in Manhattan.”“Say what?”“Who’s the other guy…you know, the one you like…”“On the Orioles?”“Say it right. Traitors! That’s what they are. A bunch of stupid-ass, stinky-toed traitors.”“Stinky-toed?”“So, the Orioles real name is—or should be—the Benedict Arnolds,” Nicole said.“You know the guy, Joefish! He’s an outfielder, Benny…”“Ayala?”“No, he’s worse. He’s a former Met.”“Ayala’s worse than who, Pop?” Benny Ayala was indeed, a former Met, and current Traitor.“The guy you like! He came up in ’70!”“You mean…Singleton? Ken Singleton?”“That’s the guy! Simpleton! What a mutt!” “Because he’s an ex-Met or because he plays for Baltimore?”“Yeah!”

I hurried into my room and found my 1978 Topps Baseball card of Ken Singleton. It was the first card I ever came across in a pack I purchased and thus, the first one I ever owned. There was something about his name. Ken Singleton sounded like the name of an athlete, or one that befitted a Super-Hero’s secret identity. Tony Stark was Iron Man, Ken Singleton was Oriole Man. When I first looked at his main stats for 1977: 28 Home Runs, 99 Runs Batted In, .328 Batting Average, I was impressed, but when I saw that he was from Mount Vernon, New York, I became a fan. I didn’t know where exactly Mount Vernon was, but the fact that it was somewhere in New York sufficed. Ken also batted from both sides of the plate: his super-power.

I always watched with concerted interest when the Yankees played the Traitors. I loved Ken’s game; his intelligent approach to hitting, preferring to accept a base on balls than swing at a pitch below his knees or outside the plate, refusing to get himself out; his consistent outfield play, aggressively chasing fly balls, gunning down runners with the accuracy of an assassin. As for Mount Vernon, I looked it up in the M-N volume of my World Book Encyclopedia set: my childhood Google search engine. Mount Vernon was just above the Bronx, the cradle of my baseball fandom.

Perhaps part of my fascination with Ken Singleton; with Thurman Munson; with baseball, and maybe professional sports in general lies in the merging of cultures. For me, watching two teams compete against one other is to watch groups of people representing places: the individual hometowns of the athletes, the collegiate settings of their student-athlete days, and the cities they represent as members of teams. Sports franchises’ fan-bases are often couched in locality: part of a baseball game’s allure is as much a tale of the citizens and customs of two cities as it is having a hot dog and a beer. Or three. In watching baseball as a child, I was exposed to people from backgrounds and places that I didn’t otherwise have access to. Reading about innumerable cities and towns on baseball cards was to travel anywhere my little pancreas desired, without parental consent, determination, or reliance of storytelling. For some, baseball cards opened dialogue for people who liked to trade. I saw them as Geography lessons with free bubble gum. When my mother spoke of Italy, she did so by memory, having been born and partially raised there. She also spoke of Italy as “a launchpad to America;” to a better life, as transforming from Italian to American. Her recollections and sense of ethnic identity were my leaps of imagination. Coupled with my mother’s stories, my main sense of Italy was in the food my family ate. Baseball gave me the lay of my native land. In so doing, I began to see beyond my neighborhood’s wilderness of clothes lines and rusted stop signs. By learning about the world beyond New York, I began to learn about Italia: the home plate of my immigrant heritage. Baseball may be the All-American Pastime, but my sense of being Italian is being Italian-American, which has as much to do with Ken Singleton and Thurman Munson as it does with Sunday Dinner or eating the seven fishes on Christmas Eve.

My baseball-card muscles pumped, I swaggered back into the kitchen. My father was still talking smack about Ken. Little did I know that I slid into a nerve, feet first.

“Simpleton? Craptacular player. The guy was craptacular with the Mets, craptacular with the Expos, and Captain Craptacular with the Traitors now. What’s the attraction, Joefish?”

“He’s from Mount. Vernon. It’s really close to the city, Pop.”

“Mount Vernon, my ass! Simpleton’s a traitor! At least the Mets got Rusty Staub for him. A New York guy in Baltimore. What a flop.”

Nicole chimed in. “Ken Singleton didn’t choose to be traded to the Traitors, Daddy. Besides, he’s cute.”My father shook his head. “Fuck Ken Simpleton! The guy was allergic to wool uniforms. If you can’t wear the uniform, you can’t play, in my book.”

I flexed my baseball-card muscles further.

“Thurman Munson was born in Akron, Ohio,” I said. “He’s not a native New Yorker, and you love him, right?”

My father looked at me as if I was giving birth to a squid.

“I mean, the Yankees drafted him out of college. He’s an Ohio guy, and you love him.”

My father pumped his fist in the air triumphantly. “Right! He’s a Yankee. Always was, always will be!”“But—“You gotta be different, dontcha’ Joefish? Anyway, we’re going tomorrow night. I took the day off.”

***Our bellies filled with Onion Pie, we entered the on-ramp of the Triborough Bridge. We were in our first new family car, a 1979 Chocolate-Brown Cutlass Supreme, which we called the SS Snickers. It was busy, but we seemed to be a couple of steps ahead of the impending gridlock. My father could not only drive well, he was a master anticipator of how the ebb and flow of traffic would manifest itself: a natural, as scouts often said of Thurman as a catching prospect. Small wonder that he won 25 straight safest driver awards: the MVP award for bus drivers in New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority. A quarter century’s worth of outstanding job performances between the years 1970-1995 to Thurman’s one in 1976.

I looked outside my window. Planes were headed towards LaGuardia’s watery runway. I wondered if anyone was coming to New York for the night’s Yankee game. The entire Yankee team and their families were on the flight for all I knew.

“Welcome to Babe’s house,” my father said as we rolled onto River Avenue. Yankee Stadium stood tall: a resplendent figure in its navy blue, white, concrete and steel glory under a sky of gathered storm clouds. A monument to winning, surrounded by rusted fire escapes, boarded windows, and strawberry-blonde brick buildings which seemed to form a proud, long-toothed grin in the mouth of the grizzled, tougher-than-leather South Bronx.

Chic’s “Good Times” crackled from the radio:Must put an end to this stress and strife, I think I want to live the sporting life. Good times, these are the good times. Leave your cares behind, these are the good times.“Will you please put out your cigarette, Daddy?” Nicole said. It wasn’t a request.“Sure, Pepsi-Cola.”My father flicked his ashes outside his window, and they promptly pelted Nicole’s eyes like a Goose Gossage-thrown fastball.“Daddy!” My sister yelled.

“The eyes have it,” my father said, laughing. Leave your cares behind.My mother sighed, and the Snickers dodged and weaved through the stadium parking lot like a metal prizefighter. The littered ground shook in Styrofoam fear as seagulls pecked at cracked Big Mac containers. I listened and looked up: the rattle of the departing B-train was like a sip of Napa Valley-made wine after crossing the Urban Renewal desert. My father parked the Snickers after paying to do so.

The stadium was teeming with people, even though we were nearly two hours early. We were in the Upper Mezzanine of Right Field, which Nicole was stoked about. She told me that a lot of foul balls and home runs came up this way, since it was the shortest part of the Stadium. Maybe we would catch a souvenir, courtesy of Puff Nettles or Mr. October. My heart’s bass-line thumped at the prospect.Another possibility: a ball hit by Singy. There he was, Ken Singleton himself, playing catch with his Orioles teammates Rick Dempsey, an ex Yankee; Thurman’s onetime backup catcher, no less, and Jim Palmer, in his movie-star handsome, cap-less, perfectly feathered-hair glory.

“Traitors!” My father yelled.

Then I heard The Voice of God. Bob Sheppard, the Stadium’s Public Address announcer:“Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to Yankee Stadium.”

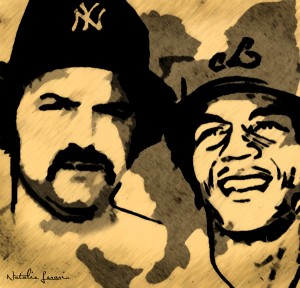

The silver dust of Mr. Sheppard’s voice made the crowd erupt with a choir of applause and whistling. I saw galaxies of goose pimples bloom on my father’s forearms, and he directed my attention to the scoreboard in centerfield, which was alight with a head shot of Thurman. His round mouth open, dark eyes intensified by the scoreboard’s monochromatic and orange hues, like the chest protector he wore for 10 years. His full head of hair, sideburns, and mustache accentuated a half-smile, forming on his face like a man who has falling in love at first sight.

I glanced at my parents. My father’s eyes were watering. Nicole handed me a pair of binoculars and pointed towards Right Field.

Reggie Jackson stood, head down, in the bespectacled flesh, his number 44 hulking in the binocular lenses. He appeared to be taking off his glasses. “No way,” I said.

Mr. October was wiping his eyes! He, too, like every other adult in the stadium, was crying. The Law Giver Bleeds. Even Mr. October, the Yankee cleanup hitter; the great Reggie Jackson cries.It was almost too much to take in at once. There was Reggie, weeping openly in Babe’s house. As sad as everybody in the stadium was, I couldn’t shake the feeling that maybe his teammates knew him differently, if not better. And perhaps, I thought, none of them knew him quite like Reggie did, having pissed Thurman off something awful when he referred to himself as “The straw that stirs the drink…Munson can only stir it bad” in an interview with Sport Magazine a few years earlier.Even Robert Merrill’s elegant baritone was wavering a bit, as his rendition of the Star Spangled Banner echoed through the stadium. My father was especially observant of this, likening Mr. Merrill’s rendition to “a sung eulogy.”

I asked my father what a eulogy was. “It’s how you say good-bye to the people you love.”“Like when you go to work?My father grinned. “I’ll always come home from work, Joefish.” Then he pointed to the scoreboard, which was alight with the following words:“Our captain has not left us—not today, not tomorrow. This year, next…our endeavors will reflect our true love for him.”

The words were then replaced by the image of Thurman’s face. My father cleared his throat. “These are the words of a prayer, for a funeral without a casket.”“I see,” I said, not seeing at all.

The game was nationally televised for ABC’s “Monday Night Baseball.” I could only imagine what Howard Cossell, Don Drysdale, and Keith Jackson were saying on the air. My Mother offered my father a sip of her beer. “My mouth is too heavy,” he said. Nicole consoled him. “Maybe we’ll be on television, Daddy.”

Other than the Traitors, everyone else in the stadium seemed to move around in a torpid state. Even though I saw Ken Singleton hit a home run and Ron Guidry pitch, my only relief came from Bobby Murcer. With the Yankees trailing 4-0, Bobby hit a 3 run homer in the 7th and then, with a bat he would never use again, a walk-off two-run single in the bottom of the ninth. Bobby’s hit sent us into a frenzied outpouring of screeched gratitude for having come through for Thurman. The noisy shirts of championship flags flapped polyester enthusiasm for Bobby as he crossed home plate, streaked with a mustache of dirt.

When the game ended, the crying resumed. People wept just as much as they did before the first pitch. The bottoms of my eyes were as puffy as the thousands of adults surrounding Nicole and I. Even though the Yankees came from behind to win the game, the high of the victory had crashed like Thurman’s jet. Looking back on it now, I not only joined the crowd in mourning the loss of my favorite ballplayer, but I also sobbed because the game was the first stanza of my childhood’s final poem. I went to my first baseball game as a green fan and came out a seasoned griever. No one close to me had died previously, and I had never heard a eulogy before.

On the way home, the Snickers was once again bathed in the sounds of the car radio. I remember hearing the song “We Are Family” by Sister Sledge, and then AM talk. I learned that the entire Yankee team attended Thurman’s funeral in Canton earlier in the day. That they won the game delighted me. That they summoned the energy to play a baseball game after a funeral astonished me. I also learned that Bobby Murcer, the day’s hero; Thurman’s closest friend on the team, was a eulogist at the funeral. He was also the last Yankee to see Thurman alive. Baseball aficionados and non-sports fans alike were sympathetic to Thurman’s wife Diana, now a widow having to face the reality of life without her husband and raising three children on her own.

As unaware as I was of these facts during the game, I have since learned that my love of baseball is as much to do with the personas of the players as it does with location. What the Coliseum is to Rome, nicknames are to baseball; an essential part of the culture. Some are world-famous: Mr. October. Catfish. Whitey. Babe. Others are comparatively less-known by the public or casual fan, and more by die-hards, haters, and home-team insiders. Pepi. Gator. Puff. Sweet Lou. People leave their native lands for work and opportunity, and sometimes they die in the process, like Thurman did practicing take offs and landings in Canton; like some members of my family in boats from Italia to America. Thurman was learning how to fly so that he could spend more time with Diana and their children. As a bus driver, my father commuted to work, trading one set of traffic after another, in the name of familial love and honor: “I make a living to make a life,” was how he put it to me the night before I went away to college. This sentiment was my inheritance, my ancestral tradition; the pinstripes on the shirt I was groomed to wear on my back.

My family has since been fragmented by divorce, growing up, relocation, and other assorted forms of sacrifice. In my case, my current professional life in New York had to begin someplace else, as I told my Father when I moved to Northeast Ohio to teach at Kent State University, Thurman’s Alma matter, for my first paid teaching job. Babe’s house was demolished and has been reincarnated into “New” Yankee Stadium, across the street from the old one. On occasion, when I visit the city, I stand on a subway platform waiting for the B train. I always see people wearing Yankee jerseys, whether it’s baseball season or not. The names on the backs of the navy blue Yankee t-shirt jerseys are lyrics to the rattling of the subway cars: Jeter, Pettite, Posada, and Rivera, all of whom are players of my generation, people who came to baseball at the same time that I did, but were blessed with the talent to play the game for a living and with distinction. On my most recent trip, I saw a teen-aged boy sporting a Munson jersey. Tanti saluti, Thurman, I murmured to myself. The train doors opened; a squeak of recognition and remembrance, gone in a spin of my Ipod dial as the train hustled out.