The bulge of my dad’s cheek got smaller when his mouth was open and the chewing tobacco was on his tongue. His eyes strained, looking up, the way he looked when he clipped his nose hairs in the mirror. His black boots were unlaced, tongues lolling from a hard day’s work. Stumbling, the clack, clack of untied laces whipped the leather of his shoes. His gloved hand was outstretched, trying to catch the ball I’d thrown. Dad was about three feet from it when it hit the ground and rolled, a rabbit darting through the grass, past the tool shed and down the hill, towards the creek.

“You’re throwing rainbows!” he hollered, wiping his forehead with his flannel shirt sleeve.

Nolan Ryan made a change-up look so easy. I could hurl a softball twice as far as most girls, faster too, but I couldn’t slow it down on purpose. It made me feel like a girl. The grass in the yard was moist, so I slipped and ran down the hill to get the ball from the edge of the creek where it was stuck in the shallow mud banks threatening to wash away into the river.

“Grab it like this.” Dad was across the yard again. I couldn’t see how he was holding the ball.

I ran to him as fast as I could. His stubby hand was wrapped around it, so natural, like it grew there. His top knuckles were on the laces, just the tips of the fingers across the white stitching. I took the ball from him, my fingers in all of the right places, copying his hold. I walked back to my side of the yard, eyes forward and narrowed, hand lightly squeezing the ball: This is how it should feel in your hands. This is how Dad throws a change. I threw it, grunting with the release and watched as it sailed, the same speed, the usual spin. It fell at his feet because he didn’t try to catch it this time. “I think it’s your wrist,” he offered. A long black stream of tobacco spit hit the ground.

“My hands are too small,” I said to my shoes.

It was on another of those hundreds of Fall days when Dad and I threw a ball in the yard until Mom yelled it was time to eat dinner and isn’t it too cold and dark for ya’ll to play, that I thought I had found a solution to why I couldn’t make a football spiral or a softball change speed.

“Do you ever wish I was boy?” I asked my dad.

He just looked down at me and said no of course not why would I ever wish that and what made you think that?

So I could be tough and not have to wear dresses and pink and so I could finally cut off the hair that fell below my waist. So I wouldn’t have to help the women wash dishes on Thanksgiving and Christmas.

“I dunno,” I said.

I was sure I’d be the first professional woman playing baseball and football: a female Bo Jackson. I knew my life would not be complete until I had seen my last name across the back of a St. Louis Cardinals’ jersey, though I knew my last name wouldn’t even fit. I imagined the letters running across the back of my shoulders onto my arms, like R. HENDERSON or RODRIGUEZ. On a 49er’s jersey, though, the name might fit because the shoulder pads would offer more of a surface for the lettering.

“Someday I’ll play with the Cardinals.” I said to Dad.

“We’ll keep practicing, babe.”

* * *

I was five when my best friend told me she was going to play t-ball. I assumed I was signed-up too. The first game was in a week. I asked Dad about getting a new glove and some pants like John Kruk.

“You’re not playing t-ball,” he said.

I thought I was being punished.

“That game is for pussies. They’ll never learn to hit.”

Dad said there was no way in hell I was gonna play T-ball. I cried for a year, listening to Dad’s argument, finally internalizing that the only real way to learn to hit was from a ball being thrown, not some damn ball sitting on some damn tube. When my best friend asked why I wasn’t playing, I told her, “T-ball is for pussies.”

So Dad found a team thirty miles away, the next town over, that played “coach pitch” and he signed us up. And he coached me every summer, every sticky mid-western burnt corn summer. Every keep-your-eye-on-the-goddamned-ball-I’m-gonna-nail-your-feet-to-the-ground-use-two-hands-get-your-gate-down-you-kicked-ass-tonight-babe-Dad’s-so-proud-of-you summer.

* * *

It was Easter morning the next year and my family was gathered at my grandparents’ kitchen table waiting for my Uncle Jeff to walk in the door so we could all walk together across the yard to the Episcopal Church. He hadn’t come home the night before and the family cracked jokes about him finally having found a woman. The phone rang. Dad and my Uncle Jerome left in one car, my grandparents in another. I was six years old.

They found Jeff’s truck upside down on a creek levee only two miles from home. While my grandparents waited on the road with the county sheriff, and Jerome turned away, saying he just couldn’t do it, my Dad walked to the overturned truck and saw Jeff, smashed against the windshield, crushed against the dashboard. The county sheriff waited. That’s him, my dad told him.

The whole family stayed waiting in my grandparents’ yard as the old church bell rang. I was wearing a frilly dress that my mom and I had fought over for an hour earlier that morning, my long blonde hair combed and an Easter hat bobby pinned to my head. Grandma and Grandpa pulled into the driveway, then Dad and Jerome. Grandma got out of the car, one foot, then another. She paused. Then she rose from the car seat, her hand over her eyes and stood there, the other hand grasping the open door, until Grandpa came from the driver’s side and grabbed her round the waist and led her down a small slope in the yard. She walked that way a few steps, then she broke free. Grandma began trotting down the yard to the house where we were all waiting in a circle. Her purse bounced, dangling from her arm, forgotten. Halfway to us she stopped, her big plastic glasses moving with the scrunching of her face. “Jeffie’s dead.” she sobbed. “My baby is dead.”

He had been twenty-two, a first-baseman who broke rural high school batting records. I was just tall enough to peek over the side of his casket, just tall enough to smell the embalming fluids or make-up or the flowers of funerals, whatever that smell is. Dad lifted me; his hard calloused hands were vises around my waist. He held me so I could look in. It wasn’t my first funeral. I knew the orange make-up that would be covering his face. I knew he’d look like he had an inch of fake skin. Everyone said he looked so good but I never understood how someone could look good dead, covered in make-up. Beside Jeff’s left arm lay a wooden Louisville slugger with the graffiti of his teammates’ signatures running the length of it. The suit he was wearing was blue and ribbed. He looked strange not wearing cut-off shorts and high school mascot t-shirts. His fingers were laced together on top of a baseball, the red stitching like blood oozing from small cuts. I watched as my Mom reached in to pat his hands, her face drawn and tight, head nodding yes he was good yes he is dead yes. I reached out my hand, too. Dad adjusted his grip on me, suspended me over Jeff’s body, bird’s eye view, my long hair falling around my face. I touched his hands and the baseball; both were cold and hard.

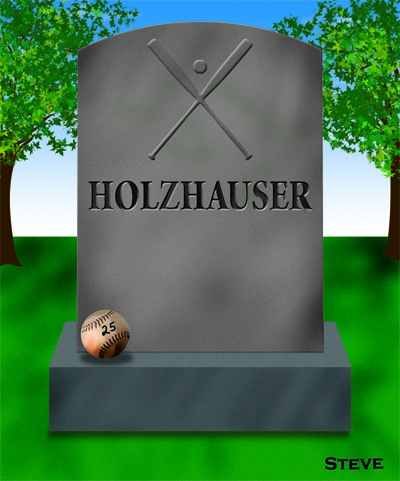

His tombstone was nothing fancy. On either side of his name were my grandparents’ names, the dates of death left open. “Did Grandma and Grandpa die, too?” I asked my parents. It took years for me to understand the concept of a pre-paid burial plot. A bat and baseball were etched into the tombstone above the last name, HOLZHAUSER. I thought, When I die, they will put a baseball on my tombstone, too.

Jeff used to play wiffle ball in our yard with the neighbor boys. I was too young, too small to play, so I had to watch off in the distance, every once in a while racing our dog to retrieve the balls that flew too far. We developed this routine. It took place every night after school, and I began to take my position as a fan seriously. Digging through a box of my baby clothes, I found a baseball style t-shirt and wiggled my way into it, the arms were too tight and the bottom only covered some of my ribs. I couldn’t think of any teams that Dad liked that had the color pink on their jerseys. “Mom, what does this say?” I pointed to what was written across the front.

“Angel”

“Does it say California anywhere?”

“No.”

Dad and I didn’t like the Angels, at least he never said much about them, but I wore it anyway figuring it was the closest thing I had to a baseball shirt. I went to my bedroom and pulled my fake Cardinals batting helmet from the nail on the wall. My grandpa had bought it for me the last time we went to St. Louis. So I let the cheap plastic beat against my head and ran outside to watch the game from the cracked, sun baked porch. And I did this until I was old enough to convince the boys to let me play or Dad made them, it’s hard to say.

Dad told me once he played football in middle school and was sure he would’ve been great, but his family moved. They moved to where I grew up, and there wasn’t any football at my school, seeing as how it was stuck out in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by corn, soy beans, and flood water. Dad played baseball, too, and he played at my high school. But because his parents owned the bar in our town, they were too busy to come to games or pick him up after practice. He would walk home, eleven miles, or hitchhike. I always pictured my Dad, seventeen years old, eyes on his shoes, his hands minus thirty years’ of work gripping the knob of a baseball bat dragging it down a country highway. Maybe he stopped every once in a while to throw a rock straight into the air and bat it away, over the road as far as he could. Maybe he would take a few low practice swings on the newly planted corn. It’s possible he walked the railroad track to cut off a mile or two. Limestone bluffs as tall as silos on one side of the tracks, caves dotting the hillsides, the limestone too soft to resist weather. But on humid spring nights I still see my Dad, a poor country boy with a shock of brown hair, walking home at dusk, the fog from the river just starting to rise and creep through the fields. And my Daddy, a shadow of a man, walking home.

* * *

I would always try to be the last to leave after my softball games. The moisture would fall from the sky like heavy, slow rain around 8:30 every night; the thick mist hovering around the lights of the baseball fields formed one large bright and blurred foggy bundle of air. Whether I was wandering out in center field or talking to teammates, I was always stalling. Every game felt like the last game of my life. I never took it for granted. I’d hide in dew-covered metal bleachers and try to see the hills through the lights and the dense fog.

It would always happen that Mom would yell for me just when night was pushing the light of day deep down, over the horizon, behind a line of trees. I would run, still full of energy. In fact, more full of energy after a game than before. I would sprint to the truck, the whole time twisting my weak ankles as my rubber cleats clawed at the gravel for traction. I’d mount the tail gate of the truck like a pommel horse, swinging my legs and pointing my toes just like my gymnastic teacher instructed. I was graceful. I knew I was. I’d slow down my body like those guys on the rings just to show people how skilled I was at slinging myself into the back of Dad’s red Ford. I loved the thump my feet made as they hit the paint-chipped bed.

Mom would argue that I should ride in the cab, but Dad would usually give in and let me ride in the back of the truck. I’d grab an old folding lawn chair and prop the back up against the window. As we pulled out of the parking lot I’d give a last look to the ball field. As the field lights were shut down, my heart would flicker, and my excitement would fade to melancholy, though I had no word for the sadness I felt. I had a feeling I was a small part of something much bigger. What that was I wasn’t really sure.

Going fifty-five down Highway 94 I learned to love the chilly night air. This was the road my Dad used to walk. The dampness of the river air brought out a musky smell from the fields. I could close my eyes and know the difference: Soybeans, Soybeans, Corn, Corn, now Soybeans. Mom would try to check on me. “You okay?” she’d holler through the pane of the sliding window. I pretended not to hear her. I’d just stare at the sky, all the stars, and count the eyes of deer out in the fields.

The ride only took twelve minutes from the field to my house. That road that my dad walked for hours, kicking rocks, sticking his thumb out. When Dad would back us up into the driveway, I’d sigh. I exist in the world. A chorus of tree frogs, bull frogs, crickets sometimes so loud I couldn’t sleep. I was home. The moon floating on the river and in the sky. Ball glove still on my hand, rubber cleats slipping on the dew settled into the truck bed, hair matted from dirt and the wet of Midwest nights, I’d jump to the ground, to the same yard I had learned to catch and throw in and where Dad practiced with me until we had enough. I’d take a last long look at the sky on the way inside and run straight to bed without showering.

* * *

It was my junior year of high school. My grandpa had been sick for months and on peritoneal dialysis, so when he went back into the hospital that week, no one thought much of it. Then Mom drove up during softball practice one evening. She didn’t really look at me, just stared past me into the trees, out over the river bottoms. Without anyone saying a word to me, I grabbed my ball bag and told my coach, “I have to go.” He nodded, the first time I’d seen him not scowling.

Five o’clock the next morning, after sleeping in spurts on two orange plastic chairs pushed together in a waiting room, and sometimes under the couch, I was standing beside my grandpa, his body thin and covered by a white hospital sheet. When I saw that Dad was crying, my own eyes stung and began to blur. My parents shuffled me in front of them, right up close to the skinny hospital bed. Mom whispered in my ear, “Tell Grandpa you love him.” Dad put his lips to my other ear, “Tell Grandpa you’ll hit a homerun for him.” His skin was so pale I thought I could see through it. I was almost mad at Grandpa for putting me in such an awkward situation; I never really told anyone I loved them. But I knew if I didn’t say it now, there would never be another chance. I held his hand, “I’ll hit a homerun for you,” I said my voice wavering. His sun-spotted hand squeezed mine and I saw a weak smile through the plastic of the oxygen mask. His other hand reached for the mask and Dad told him no, to leave it on. I noticed the turquoise and silver ring Grandpa always wore was missing from his finger. He tried to say something anyway, but the noise of the oxygen mask was all I heard.

There were at least fifteen people standing around his bed when it all ended. Grandma held his hand as we all watched. The nurse inched through the crowd to stand with the doctor. The oxygen mask had been removed. All eyes were on Grandma and the woman nodded for final approval. Grandma nodded back. She pushed buttons on machines and they let out a sigh. My grandpa, Nelson (Buzzy) Holzhauser, lover of the St. Louis Cardinals and everything baseball, veteran of the Korean war, funniest story-teller in Portland, Missouri, the man who used a curse word every other word he spoke, now gasped for oxygen. The man who taught my dad how to play baseball struggled for life. His chest heaved so hard it made his whole body rise from the sterile white bed and come down with a thump, like someone lying under the bed trying to kick him out. Thump. Thump. He kept his head turned towards Grandma the best he could. It was all so absurd I was thinking. A whole family here, staring at this man fighting for his life. I felt dirty, terrible for staring wide-eyed at my grandpa. I was embarrassed that he was too weak to live. My body felt like it was bursting and I let out one huge sob, like a bark and decided to leave the room. Exhausted and confused, I stopped and stood behind the privacy curtain there in the ICU and pulled it tight around me like a blanket. I didn’t want Grandpa to see me there, if he could see at all, wherever he was in time and space. Through the one inch gap in the curtains, I watched my grandpa die.

He was buried beside Jeff. Ten years had gone by while my uncle waited for his parents to join him on the hill overlooking the river. Grandma gave me Grandpa’s favorite Cardinals jacket. Every summer it seemed, Grandpa had sponsored a Holzhauser family Cardinals game trip. We’d pack into several cars and make the two hour drive to St. Louis. During the 7th inning stretch, the Budweiser Clydesdales would pull the wagon around the field, full of wooden kegs of beer. Grandpa would raise his own plastic cup of the stuff and hoot and holler with the rest of the crowd. When Ozzie Smith would hit a homerun and do a back flip on his way to home plate, Grandpa would nudge me with his elbow, his crooked bottom teeth sticking out, “Aren’t you glad you’re taking gymnastics, too?” I would giggle like that was such a silly idea, but all I ever wanted was to play baseball-right there in Busch Stadium with Grandpa, Dad, Jeff everyone, watching me. I pictured myself walking up to the batter’s box, my specially made bat knocking the dirt from my metal cleats. Maybe the first pitch I would be too anxious, maybe a little too nervous to swing. I’d pull the next one away (oh, to be able to hit it wherever you liked!). And then the pitcher would try to throw me a change, but I would be ready, you see, watching the motionless laces as the ball floated through the air. I would crank it. Crack! That noise and the feeling of knowing that your mind and your muscles were all there at once, making something happen, the vibration of the bat that runs down your arms and into your chest. I would stand, the bat dangling in my left hand, watching as the tiny white ball flew into the upper deck. I wouldn’t walk around the bases because it seemed rude. I’d run, and just before home I’d do a back flip and cameras would flash and Grandpa and Dad would be right there, running out of the dugout or something. Dad would say, “Good job, babe” the wad of chewing tobacco trying to make its escape through his wide smile. And Grandpa would follow that with, “Hell of a hit, there, munchkin.” Jeff might just smile at me and tousle my hair. Maybe Grandma knew all of this, could see it in me somehow, and so she gave me my grandpa’s Cardinals jacket.

* * *

Once, after a soft-ball game, I raised my can of Mountain Dew in a victory toast. Surrounded by my team, a mob of fourteen year old girls with their hair in pony-tails and blue scrunchies, I said, “Guys, this moment in time will never happen again. We’ll never be able to come back and live this moment. We’ll never all be here together with these sodas, and our winning season, and this night again. This is a memory we can all share when we’re older, these are the things we’ll look back on and say remember when. Know what I mean?” Mouths puckered in attempts to understand what I was saying, cleats danced in the gravel as people shifted their weight from one foot to another.

“Kinda,” someone answered.

We toasted anyway and the group dispersed to find boyfriends and parents in the parking lot.

* * *

Grandma and Grandpa had Jeff’s baseball glove bronzed after he died. It still sits on a shelf in Grandma’s living room. His class ring dangles below the glove on a wooden peg next to his hat. His personal bat also sits below the mitt. Above them in a large frame is Jeff’s jersey, folded to show the number 25, retired by my high school, given to the family folded like this, like the flag Grandma got when Grandpa was buried. Also on the wall is a picture of Jerome, my other uncle. He’s pitching, his body stretched in all angles, the veins and tendons popping in his neck, the ball just leaving his fingertips. In twenty-three years these mementos have hung in the same spot, taking up more than half of a long wall. Another picture; my grandpa sitting on a metal folding chair, his Cardinals jacket on. He’s watching Jeff swing just outside the on deck circle.

* * *

The first phone call came in September of my senior year of high school, not too long after my parents found out I was a lesbian: a college asking me to play softball for them for a scholarship; they’d even pay for my books. Other colleges called and called, but I just said no thanks and hung up and cried at night. I had already decided to move Houston for college, to be with my girlfriend, and unfortunately, there was no softball team. My parents were furious about the news, screamed at me for hours, things like hell, dyke, disgusting and eat her out came from their mouths. Things they had never said, things I hadn’t had time to think about. They said other, more hurtful things, too.

“A lesbian?” Dad asked, his face reflecting the fire burning somewhere deep inside him.

“I guess.”

“You let her play too many sports!” Mom yelled at Dad. His defense was that she let me quit dance class too soon.

“What the fuck are you thinking? You’re fucking up your softball career!” He screamed in my face. “There’s no way you’ll go to the Olympics like that.”

My Dad, 240 pounds of muscle and country boy, fell into his favorite recliner, his hands covering his face, tears streaming down his forearms. Through his crying he coughed out, “What would your grandpa think?”

“I don’t care!” I said.

But I thought about giving up softball as much as I thought about the way my family looked at me now, like I was a freak, like they always knew something was wrong. What could I do with softball anyway? That’s what it all came down to. I always knew I could never make money from sports. It wasn’t fair. What was the point of knowing so much and getting so good when after college you had to get married and have babies? Boys were different. They could play ball their whole lives. They could play in college, and if they were good, they could play for millions of dollars a year. Their hard work could pay off. They could stand on the grass at Busch Stadium and have their grandpa and dad in the stands. I was fast, had a glove, could cover a large area, throw strikes from center field, colleges wanted me, but what after that? It didn’t matter, wouldn’t matter when I was thirty or even when I graduated at twenty-one. A career was more important than softball.

The first relationship where everything made sense was more important than a game, I told myself.

* * *

It was three years after grandpa died, two years after I started college, and it all felt too big. I was in Missouri, visiting. Earlier in the day, my parents and I had come into town and driven past the cemetery. I always looked at my last name on the headstones. Whoever had just mowed the cemetery had thrown all of the wreaths and flowers away. There was nothing decorating the grave.

As soon as we got to my parents’ house I went upstairs and found a softball, a new one. I found a marker, and I walked out the door before Mom and Dad could ask where I was going. I started walking towards the cemetery on a gravel road, tossing the softball and catching it. Gripping it like I might pitch a rise, now a drop, now a change. I wanted to throw it as far as I could, get it away from me, let it roll into the woods and decay. I wanted some kid to find it years from now just a lopsided ball of string, the cover lying open like flower petals on the ground under it. A ball of twine blooming from two pieces of leather.

When I got to the cemetery I felt stupid. What if someone saw me roaming around the graves? They’d call my parents and tell them I’d gone crazy or was about to vandalize something. I stood by the tombstone and ran my finger over the letters of my last name, then traced the baseball engraved in it. One of the few things I could remember from Jeff’s interment was that my cousin, who was eight, was wailing. It had made me cry harder when I saw her. I remembered Grandpa’s funeral better; the whole town had shown up, my Dad was a mess, my Mom held him during the service. It looked funny that this tiny woman held a man twice her size as he cried. My Dad cried twice that year; once for the death of his father, and once for the death of the person who he thought was his daughter. There was the twenty-one gun salute: Fire! Fire! Fire! with the smoke settling on the crowd like a cobweb, the rigid folding of the flag, Grandma, and the trumpeter, casting his sound out over our small river town.

I sat on the ground in front of the tombstone, in their laps, and felt the moisture of the grass seep into my pants. I took the marker from my pocket and wrote the number 25 on the softball. It was Jeff’s number, but as it turned out, it had also been Grandpa’s number, and my Uncle Jerome’s and, of course, mine. Then I wrote their names. Jerome Holzhauser, Jeff Holzhauser, Joe Holzhauser, my Dad, Buzzy Holzhauser, Great-grandpa Herman Holzhauser. Great-Great Grandpa Adolph Holzhauser (played professionally they tell me)-all ball players. And then something happened. It was something I’d thought about in fits and starts since I could remember. Who would pass on our name? Jeff was dead, Jerome was done having kids and had made a girl. My parents couldn’t have children, the reason they adopted me. That left me and my cousin Renee. She would marry a man and take his last name, there was no doubt. It was all up to me to give my children my last name. When I was younger I worried about getting married and giving up such a great last name. It was a name that people around our small part of the world knew. “Aren’t you that Holzhauser girl from Portland?” Or, “You act just like a Holzhauser.” I said once, when I was ten, that my husband would have to take my name. I’d have to have a son and give him my last name, teach him how to play ball. My worst fear was having a daughter who couldn’t play ball, couldn’t hold her own with the boys, like me. What if she threw like a girl? Was afraid to get dirty? No, there were no more like me, I was sure. I was better off having a boy: he’d keep the name, keep the tradition, have a much better chance of making it. So I wrote my initials on the softball, knowing damn well that all the weight was on my shoulders. I cried, remembering: do you ever wish I was a boy? I was the closest thing to a boy as a girl could get, but it wasn’t enough, would never be enough. I sobbed, the crying that sounds like dying, and dug my fingers into the damp earth.

I gathered some rocks from the driveway and made a small circle to keep the softball in place. I left the ball at the bottom of the headstone, between Grandpa and Jeff. Until Grandma found it a couple of days later, and called Mom, crying into the phone.

There are no fast-pitch teams for any woman over eighteen, just co-ed slow-pitch where everyone is drunk and laughing. Old fat men toss you the ball underhanded because they think you can’t catch or throw. I have to prove myself every time I walk onto a field. With every move I’m saying; I’ve played since I was six. Fastpitch. Scholarships. Dad. Holzhauser. I don’t throw like a girl. And those fat men usually say, “You throw pretty well, for a girl.” If I have a son, I’ll be the one to teach him how to play ball. I’ll also teach him to let the girls in town play, too. Because all girls don’t always throw like girls. And I’ll tell him that boys would throw like girls too, if they were never taught.

Because I won’t marry a man, I can keep my last name, pass it on to my children. And if they don’t play, if it doesn’t mean anything to them, the lights, the air, the dirt lines on their socks, the grit ground into their faces from the catcher’s mask, that moment when the bat hits the ball and you own the world, if they don’t understand these simple things, I just don’t know.

I played ball with my Dad less than a year ago. My parents accept my sexuality now and they love me now more than ever. Dad smiles because as hard as I try, I still can’t throw a change; he can. But I remind him I was always a catcher, never a pitcher. I throw hard, though. I throw as hard as I can until he says I’ve stung his hand. I don’t mind.

There is a picture of my great-grandpa, Herman Holzhauser, hanging between the doors of the bathrooms at the bar my grandparents owned in Portland Missouri. It was taken in 1927, a year before my grandpa was born. It’s not just a picture of him, but of Portland’s baseball team. He’s in the front, holding the bat upright, a team of eight more men behind him. I have a picture like that too, where I’m holding a bat, a huge smile on my face, the wind blowing the trees in the background. I’m holding a bat, too, but there’s no one behind me.