My mother resides on top of a mountain in northeastern Washington’s “Forgotten Corner.” A sun-catcher inscribed with her name hangs on a lone pine overlooking the deep, still waters of a lake far below. It flashes red and yellow in the morning light, spinning in the wind, marking the passage of time. At the foot of the tree, entombed in a stone cairn, is a collection of treasures–family photos, a beaded bracelet, a children’s book, a bottle of hot sauce, and a miniature Green Bay Packers cheesehead statue.

I have climbed the mountain this early spring day through patches of lingering snow to tend her shrine. I open the cairn and am saddened to see that, although it has been only a year, the treasures already have begun to deteriorate. The photos have faded, the book has become waterlogged, and the bracelet has lost some of its beads. Only the hot sauce and the cheesehead statue are physically undamaged, but all have lost some of their power to recall the person they were placed there to remember. Seven of the eight people I grew up with are still alive, but–like these fragile treasures–we, too, have started to unravel and come apart.

When I was three our father quit his research position with a chemical company in St. Louis and enrolled in medical school. I don’t remember the steady, respectable income or the regular work schedule from before; I remember having little money and not seeing much of Dad. We sold our modern, suburban home and moved to an old, rambling farmhouse rental on the outskirts of Omaha.

I am the youngest of six boys. We had left all our friends in St. Louis so now we had only each other for company. We couldn’t afford going to movies or amusement parks, so we entertained ourselves with our imaginations fueled by whatever we could find to watch on our black and white, garage-sale TV.

Mom’s hair soon began turning gray, which she blamed on the bone-liquefying, falsetto shrieks I emitted when I got scared. I blamed my brothers who went to great lengths to scare me. They blamed The Wonderful World of Disney for giving them too much inspiration. Walt took the fifth. My brothers were particularly inspired by one episode, The Secrets of the Pirates’ Inn, about three youths hunting for treasure in an old house.

A few nights later, Greg discovered a clue behind the dartboard in our basement. I didn’t notice that the supposed ancient parchment was a piece of brown paper bag with singed edges or that the writing was not in blood, as Greg claimed, but red ink. I didn’t question whether pirates played darts, how one had gotten in our house in land-locked Nebraska, or whether, “It cools the house,” was particularly piratical. After several minutes of impatient, helpful speculation from my brothers, I deduced the next clue was in the air conditioner upstairs and we trooped for the staircase.

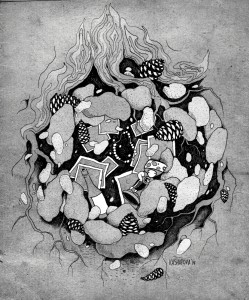

Besides Disney, my brothers also were inspired by Creature Feature, a late-night show of horror classics. They had unscrewed the light bulb over the steps, shrouding them in near darkness, and strung a fishing line just below the ceiling. Even back then, my brother Mark was a gifted artist. He had drawn a life-size, gruesome skull and attached it to a hanger with a long, white shirt. When I started up the stairs, oblivious and excited about hunting for treasure, this specter slid down the wire, streaking for me out of the darkness, and the shrieking–and the graying of Mom’s hair–began.

The next few clues led me through the bright safety of the upstairs, partly to lull my suspicions but also to give them time to prepare the basement for its next scene. Then a clue behind the TV declared, “It heats the house.” I checked several heating grates before Steve said,

“Maybe it means the furnace, moron.”

The staircase light was still out. Though I took ten minutes descending the steps, pausing on each one to look up and down, the specter from before did not reappear. When I reached the bottom, the basement I knew was gone.

My brothers had transformed it into a laboratory with glass tubes (borrowed from Greg’s chemistry set) and wires running everywhere. In the middle was a gurney with a body on it. We had recently watched a Creature Feature episode in which a mad doctor grew a second head after drinking a foul potion from a beaker not unlike the half-filled one beside the occupied gurney now. After drinking the ill-advised potion, the doctor had begun scratching his shoulder, then torn off his lab coat and shirt to reveal a single eye emerging up from his flesh. It had eventually grown into a second head.

I had to pass the gurney (actually a sheet of plywood across two sawhorses) to get to the furnace. The body on the gurney was shirtless and looked a lot like Chris, but I didn’t notice that as much as the large eye peering up from his bare shoulder. Mark’s artistic talents again. As I skirted around him, I kept expecting Chris to lunge for me but he never moved–which was scarier than if he had. I reached the furnace unmolested and found the next clue.

“Seek ye the Crypt of the Vampire,” baffled me. I didn’t know any vampires, nor were there any crypts nearby. Perhaps anticipating this, the clue suggested, “He lies next to the chicken coop.”

At the edge of our yard was an old shed. It had chicken-wire in the windows, so we called it the chicken coop. I liked the idea of going outside at night even less than being down in the basement with my shirtless, three-eyed brother. How great could this treasure be, anyway? But a few taunts of, “Get the baby his bottle!” got me moving. I went upstairs, out the back door, and cautiously crept through the yard trying to look everywhere at once.

My brothers had constructed a small cemetery, complete with wooden crosses and freshly dug grave, beside the shed. Amazing what five boys can accomplish during your afternoon nap. I found the clue in the bottom of the grave. What happened next was unscripted but surpassed my brothers’ previous efforts to terrify me. We’d recently adopted a stray puppy. Her barks, like my shrieks, had been falsetto shadows of the full-throated, adult declarations they would become. I did not know she was out in the dark yard or that her voice had picked that night to mature. When deep, snarling, rib-ripping barks exploded from the blackness, I screamed and–fearing the Hounds of Hell were on my heels–raced for the house.

Just before I reached the back door, Greg stepped around the corner of the house. He was holding a broom over his head (I found out later) draped with a white sheet to which he’d attached a human eye from a plastic anatomy model. If I’d had curly hair, it would have gone straight (no dice with my cereal-bowl crew cut). And Mom’s blond hair? Turning grayer with each scream.

My brothers’ magnum opus, orchestrated by Steve and starring Paul, involved the laundry chute–a hole in the floor of an upstairs closet. A clue was taped to a glove lying on the edge. As I reached for it, the glove fell through and landed on top of the laundry barrel in the basement below. I went downstairs and flipped the laundry room light switch. Nothing happened. In the dim glow of the hallway light, I saw the glove on top of the clothes barrel and reached for it. Paul was inside the barrel, buried beneath the clothes, wearing the glove. When I reached for it, Paul grabbed my hand. I wet my pants and my brothers smothered me with Shame.

Recently, on a boring rainy afternoon, my brothers had created the Sremahs Club (“shamers” spelled backwards). Club members wore headbands with paper hands holding wads of cotton. The cotton represented Shame. Blocks of invisible Shame were distributed at secret club meetings in the chicken coop. Each member kept his block in a special place, ready to be smeared on anyone who did something shameful.

My brothers didn’t want me in the club, but Mom forced them to let me in. I wasn’t cool with my Shame. I was too eager, wasting my Shame on the slightest provocations, sometimes even contriving acts to provoke a Shaming. During the final club meeting I was accused of disrupting important Shame business by scuffing my feet on the ground and kicking up dust. The trial was short and the verdict predictable. My brothers tied me to a chair, then bombarded me with a ton of dust. I ran for the house bawling. Mom took one look at me caked head to toe (except my cheeks, where the tears had made twin, clean tracks) and Sremahs was no more.

All treasure hunts must end and, as the name implies, the hunter expects to find treasure. The problem was my brothers had none to give. Their solution on that first hunt was unique. The final clue just said, “Time is lost and so is the treasure.”

For Shame!

It has been thirty years since we moved to Omaha. Now it is my hair that is turning gray. As I watch the wind twist Mom’s sun-catcher, I yearn for the fears of my youth. Since then, I’ve learned that–when it comes to scaring–it is better to give than to receive. Sometimes I hide in a dark room and jump out, snorting and growling, when my dog walks by. She does not like this. Perhaps she does not understand, as my mother did, that boys scare each other as a declaration of love. I wonder whether, had I not caused the demise of Sremahs, my brothers still would be smothering each other with Shame. Mom didn’t mind the club or our other acts of lunacy; she just didn’t like my brothers excluding me from their games.

We have grown in different directions. Greg, who constructed the seven-foot monster, works for NASA. Mark, creator of the skull-faced ghost and Chris’s third eye, is a medical illustrator. Chris is on his fifth post-doctoral position, still stuck in the laboratory. He never grew a second head, but I haven’t felt the same about him since and still don’t like to see him without a shirt. Steve, creator of the laundry-chute glove gag, builds a hockey rink in his yard every winter and laughs himself to tears over Scooby-Doo. Paul, wearer of the glove in the laundry barrel, is a high school principal. As for me, I am—-among other things–a writer. Mom read constantly and her love for the written word rubbed off on me.

Mom supported all our varied accomplishments and delighted in our successes. She treasured intellect and I wish she had lived to see me earn my doctorate. Although the differences between us boys was great, Mom made them small by keeping us in touch, passing news through the family network. After she died, though, the network collapsed. I know that she would be disappointed, if not unsurprised, that we have drifted so far apart. I can almost hear her voice in the wind soughing through the lonely pine telling us that we’re all only a phone call, an email, or a letter away.

Time, indeed, is lost–but not the treasure.