The hours were those of hands—sunlight falling through bars, flames striping your crooked, work-worn fingers, your palms flat on your knees. Fridays and Saturdays a sun burning in your window, a jungle rising off the river, the shifting leaves of the sycamores louder than the gulls shrieking above the foggy banks. Sitting on that thin bed those stripes prowled the floor animal for the night. You touched the same things—eyes, knees, cold concrete, bars; the weight of leaving heavier than the heat of the clenched fist pounding in your heart. You circled that animal—twilight bat, rabid mongoose, drunk driving—in your own private dance of peeing, drinking, peeing, maybe singing the dreams you heard in the those brief silences after the river turned purple in the dusk.

Those twelve months in the county jail are scattered pages from a broken book. Your brown eyes of memory offer words that write my nights: the peeled, torn skins of mangos yellow blossoms strewn along a lonely path, a banana leaf flat and still on a green pool, the hooves of an ox pulling a cart of cut cane caked with red mud. Each a page to rearrange.

You were with a group of boys, all close in age, maybe eight or nine, eating pieces of sugar cane, swinging your legs to some song only you boys heard, sitting on the end of an open wagon. Boys. All wearing light colored short sleeve shirts, dark shorts, and barefoot. Boys. You, my father, your hair like a rising wave over your brow, your deep, dark eyes. Boys streaked with dust, and little pieces of broken dried cane stalks and leaves clinging to their shoulders, their hair, and still they were clean, for a moment, beyond their memories of fields. I could not remember what this photograph of was doing tucked in my small red dictionary, compressed their in the thin pages between “Find to Fire” and “Firearm to Fish.” All I wanted to remember were these boys, you, father, one of those boys there on the edge of the cart, swinging their legs, the sweet wet gush of flesh breaking in their mouths, and the strong urgency to recognize they could have called any place home (with or without the unending fields of sugar cane).

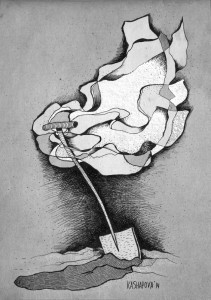

In the late afternoon, after we worked in the dusty potato fields, stood at the end of the conveyor belt bagging and stacking 10 pound bags of potatoes, after we ate boiled potatoes, fried potatoes, potatoes with mayonnaise, you changed the arc of the day by washing your white dress shirt with a bar of soap, a few black stones, squatting on the edge of a field in the irrigation sprinkler’s silver spray. Your shirt a flag without a country drying in the sun on the handle of a spade driven into the earth. A fresh bandage in the neon lights of the 5th St. Tavern.

The wound: not the fate of work, not the years of labor, not the childhood lost in the smoke of burning cane, not my reading of these pages. The memory of your hands: sleek, shiny, the sound of cloth and soap and stone alive, the smell of sweat and dirt and lemons, and in your almond eyes you already taste the rum, hear the wind thundering through the open windows, your hands steering down county roads that never seem to end, the fields fanning out towards the horizon, waiting, unbroken, no matter how much your engine roars.