California artist critiques values and the art world in his pointed works

His family was always going to go back home. Home being Seguin, Texas, where Dickson Schneider moved from when he was four years old, to go with his family to live in California. Dickson Schneider would eventually, however, set down roots in California, in the Bay Area, graduating from Alameda High School and going on to get his bachelor’s degree from California State Hayward, where he now teaches. The artist would also go on to get a graduate degree from Washington State University, where his graduate show was a 15-foot-long screen consisting of two paper screens and a block of painted wood. Says the artist, “My goal at the time was to make something beautiful.”

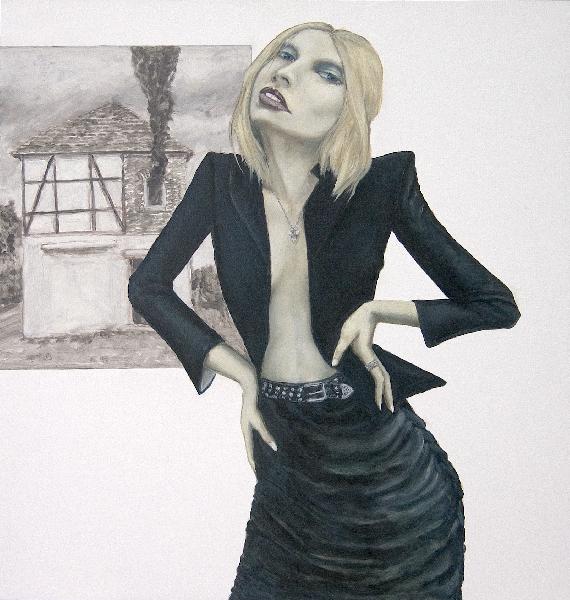

In fact, the theme of making something beautiful and his interrogation of what is beautiful, in tandem with his pointed critique of the art world, has been an ongoing preoccupation. The artist has become well known for his idealized paintings of women, except that, upon closer examination, it is easy to see these women aren’t much idealized at all, and what the artist is seeking to demonstrate in these works is that the concept of idealized feminine beauty itself is quite distorted. “These paintings all came about because a student of mine did a painting of his girlfriend that was all wrong. It was so wrong, this painting, that people could not stop laughing at it. But what I started to notice was that people also could not stop looking at this painting. For me, the painting became a moment of wrong beauty, and I became intrigued by this and started doing this kind of work. What I was going for was a dissonance between what one was seeing and what one thought they were seeing. For me, these paintings and the idea behind the work were an implicit critique of the art world.”

Another preoccupation in Schneider’s work is strong Asian influences. The artist explains these influences by harking back to a past relationship. “Growing up,” he explains, “my best friend was Chinese and I started very early as an artist to look to the East for inspiration. Interestingly enough though, my first love was and is Japanese art and not Chinese art. For a while I did a lot of work utilizing Shoji screens, and these days I am working with a Japanese manga character named Naruto.”

But it was yet again from students that Schneider gained inspiration for another engaged body of work. In 2009, during a seminar that he was teaching, Schneider heard students talking about an artist giving away his art on the street and he became fascinated. More and more he thought about doing the same thing; in time, Schneider started making art to give away as part of his artistic practice. “It was really nice to change the rules and to see how people responded to the idea of something that is free. People look at what you give them with suspicion. You can see them asking themselves, “I like this, but could it really be free?’” He continues, “The hard part of giving stuff away is the question of quality. What I have found is that you end up selling free art because people wonder about something that is free. And it does not matter if you are giving stuff away to a homeless person or a millionaire – and I have done both – people question the quality of something that is free. Consequently, my free art work is a critique of how we value things and this work is a direct challenge to the art world and art market that is so value-laden and status-driven.”

Now, however, an interesting dynamic has come into play in which people are beginning to collect the free work that Schneider is giving away. “It took people a long time to sign onto the fact that the art is as good as I can make it right there on the spot. Now, in a sense, the project has changed from me giving something away, to, rather, the transaction involved in the act of giving. The cool thing for me now about giving things away is how it makes me feel to give the work away. In the art world we have become too confused and too caught up in status and name-branding. My challenge to all of that is to get a shopping cart that I push around – what I call my crate on wheels – and engage people from what I call a ‘zero place.’”

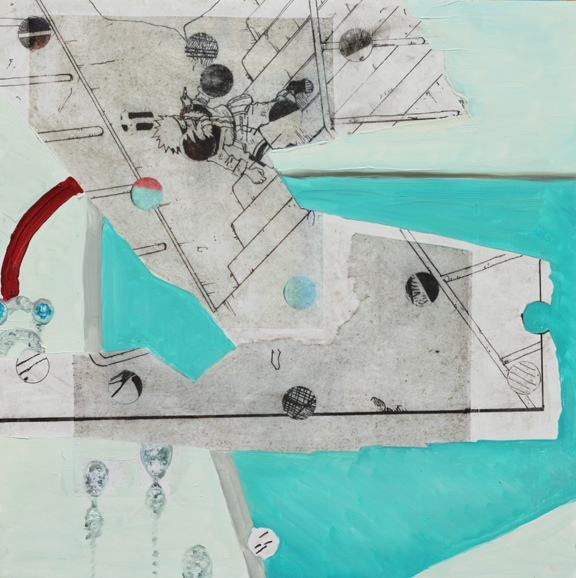

The result of all of this experimentation has left Dickson Schneider in a fertile place where he freely crosses boundaries and media. In addition to paintings, he is now doing sculpture and venturing into photography. The artist has entered a more abstract phase which involves making a series of white paintings that harkens back to his love of Asian art. Collage and bricolage are becoming increasingly important for the artist.

Until next time.