Jacqueline Bishop: Earl there seems to be one painting following another in the past few years. What accounts for this new surge of creativity?

Earl McKenzie: I took early retirement for two main reasons. First, I wanted to be able to take better care of my health. Second, I wanted time to see what kind of artist, writer and philosopher I could become if I devoted more time to these activities. After more than forty years of teaching I felt I did not have much more to prove in that area. I didn’t know how much time I had, so I turned to all three with a great sense of urgency.

JB: In addition to being a painter Earl you are also a creative writer. How do you decide what is a painting and what is a s tory?

tory?

EM: It begins with a moving of the waters, to use a biblical metaphor: an idea rises to the surface of my mind. At first I may think of it as a possible poem, story, painting or philosophical essay. But I never know for certain what is the most appropriate form it should take until I start working on one of them. I may start it as a poem and then discover that it would make a better story, painting or essay. Even a completed poem, or a part of it, may suggest a painting, or a painting may suggest a poem or story. Sometimes the idea may require all three, and they all become variations on a theme. I believe in the unity of the arts. Someone with other talents could turn the same idea into a piece of music, a play or a film.

JB: As well as being a writer and a visual artist, you are also a professional philosopher. How does your writing and your philosophy insinuate their way into your painting?

EM: Sometimes a loved phrase in a poem, what William Faulkner called a writer’s darlings, may become the title for a poem. For example the title of my painting Ornaments Against Evil comes from my poem “Burglar Bars.” There are several examples of this in my paintings. My painting Artist in a Hut inspired my short story “Graffiti”. My painting I Was Thirsty and Ye Gave Me Drink grew out of my philosophical interest in the relations between ethical behaviour and spirituality. It was my long philosophical interest in the concept of time that led to my painting Plantain Ripe, Can’t Green Again. The work of Bertrand Russell, a philosophical hero of mine, inspired my painting The Quest for Certainty.

JB: Earl, why the medium of painting for you? What can painting do, for example, that photography does not or cannot do? Have you ever worked in any other medium outside of painting?

EM: I have had some experience in graphic arts: woodcuts, linocuts and etchings; I have also done some ceramics. Sadly, all my examples of the graphics were stolen when our home was broken into and vandalized after my mother’s passing. But I still have some of the ceramics. I have no desire to return to them.

I love the feel of putting paint on canvas. I get a sensuous pleasure from it. This is especially the case if I paint during a shower of rain. A painting also has a certain intimacy that prints do not have. While, unlike some philosophers, I believe that a photograph can be a work of art, I believe there is a certain distance between the photographer and his print that I do not think exists between the painter and his painting. I prefer paintings to photographs for reasons similar to those I have for preferring handwritten letters to email messages. It is easier to sense the humanity in their production. Paintings have a certain aura, as Walter Benjamin called it.

JB: In the past others have noted your “interlocking themes of light, nature and humanity.” Do you agree that these themes are important to you, and if you do, why are they so?

EM: I regard Rembrandt, my favorite painter, as the master of light, and some influence may have rubbed off here. Scientists tell us that without light from the sun, life as we know it could not exist on this planet. So what could be more important? This is why it is regarded as the King of Metaphors.

I was born and raised in the St Andrew Hills, which I regard as one of the most beautiful areas of the island. Nature is a powerful presence there, and I cannot get away from the memory of it. I keep returning to it as both a natural and a social world. Although I dislike labels, I think my spirituality –I distinguish spirituality from religion—is located somewhere in the interstices between Taoism and Christianity. From the former I have taken the view that the Tao is the Nature from which all other natures are derived. Among the ideas I have taken from the latter is Jesus’ injunction to “Consider the lilies of the field.”

My interests clearly reveal me as first and foremost a humanist. As I pursue them I bear in mind Foucault’s reminder that historically, the concept of man is a relatively new idea, and one which could easily disappear. And Alexander Pope was on to something when he said that the proper study of mankind is man (embracing woman of course).

JB: Your work has also been framed in the past as a ‘spiritual quest.” Do you agree with this description and why?

EM: I consider it one of the most accurate descriptions of my work, especially if you bear in mind that I regard spirituality as the quest for meaning, and not as a body of religious dogmas that people accept ‘on faith’. Spiritual quests have driven virtually all my work as an artist, writer and philosopher. Northtrop Frye, my favourite critic, describes the quest-story as the oldest archetype in literature Those who fail to see the spirituality in it do not understand my work. And many persons, including critics and reviewers, often fail to see this. Let me give you an example that has been on my mind lately. My poem “A Coconut Alphabet” which I wrote in my twenties, is an account of a ‘consider the lilies’ type of quest in poetry and painting, and I regard it as one of my best pieces. I do not recall that it has ever been carefully examined and interpreted by critical writers of any kind. A recent experience changed this. During my recent poetry reading and art exhibition, in preparation for which I asked a number of persons—family, friends, colleagues, former students—to read their favorite poem of mine, Dr Jean Small, a famous actress, chose this poem and gave a rendition of it that brought out the spirituality in it with such power and force it was the highlight of the evening. Some see the spirituality and can bring it out. Others do not.

I believe life must have a spiritual dimension if it is to have meaning. And the chief function of art, in my view, is to help people live lives of meaning.

JB: What strikes me about this new body of work is the ongoing concern with the local and domestic in your work. Concern for the domestic, I would argue, is pretty atypical for male artists. How would you explain the domestic intimacy that shows up in your work?

EM: I agree with you about the local, but I can think of only one piece in this group that could be described as domestic. If by local you mean Jamaican then you are absolutely right. I was unable to paint during my years of study in Canada and the United States, but quickly returned to painting each time I returned home. I had no difficulty writing and philosophizing overseas, but just could not paint there. So painting seems to be part of my Jamaicanness in a way in which my writing and philosophizing are not. And as a painter my chief aim is to search for and portray images that I regard as fundamental to the Jamaican society and mind.

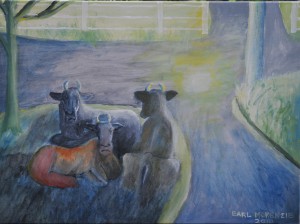

The aim is to find the image and then explore its possible meanings. For me a work of art is an object which embodies a meaning, and which can therefore be interpreted. My painting titled The Jamaican Yam Hill is an example of this. Before I painted it I had never seen a yam hill in Jamaican art. Yet here is an image that is deeply embedded in our history, economy and way of life, and therefore also has a significance and an aesthetic of its own.

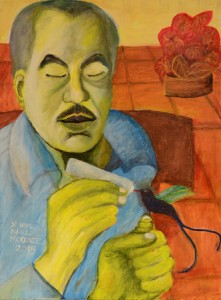

The rum bar is another important cultural object. In my painting titled The Last Drink it becomes the location for a famous bible story. The donkey’s hamper is another Jamaican image of fundamental importance. In my painting titled Inwardness I portray a hamper containing not the usual agricultural produce, but books. There is also a lamp and it is raining outside, so it is a good time for reading and reflection. This painting is an invitation for Jamaica to look inward for its illuminations.

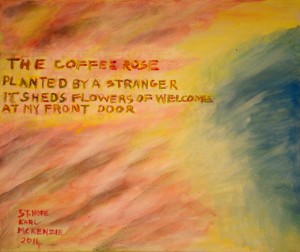

The beach is another fundamental Jamaican image. In my painting Poetry on a Beach (the title is from my poem “Sculpture Among Palm Trees), I converted a haiku I had previously composed about an actual plant in front of my apartment into poetry that, in the painting, an unidentified protagonist has written in the sand on a beach. It is right beside the sea which, in reality, could easily wash it away (although as art, it now has a Keatsian permanence). This piece, like the poem that inspired it, explores the idea of civilization in the tropics, and not, as is so often the case associated only with cold climates. I hope that someday I will be able to contribute something of value to the Jamaican visual vocabulary.

By ‘domestic’ you probably had my painting Moral Education in mind. It is a portrayal,from memory, of my mother washing our clothes in the river near our house, while I watch her from the rock on which she had placed me. (I have done another painting and written both poetry and prose about this topic) It is one of the most vivid memories of my childhood, and I also consider it one of the most important. My mother did this exercise on Monday mornings, and she always spoke to me as I watched her wash She said many things, but I still remember only one:” When you grow up don’t be ungrateful.” I think it helped to shape a philosophy I still live by: Live Gratefully.

JB: Oftentimes you have described yourself as a philosopher who paints, and that for you, philosophy was the “hub” of your creativity and painting and writing the “spokes.” Does this remain true today?

EM: Yes. The ancients said philosophy begins in wonder. I believe they were right. It is a sense of wonder about the awesome and terrible universe which we occupy, and all the mysteries and unknowns of our lives here on this little blue marble we call the earth, that is the source of my wonder-based hub of philosophy, and on which the spokes of my writing and painting turn. Kant famously said that two things moved him to wonder and awe: the starry skies above him and the moral law within him. To this thought, by the very first words by a philosopher I can recall reading in my teens, I say Amen. Except that unlike Kant (as far as I know) I also write poems and stories and paint pictures between the philosophical arguments.

JB: You have said that writing is a way of completing the artistic process that begins with painting. Have you tried reversing this process? If no, why not? If yes, what have you found out about yourself as a writer, painter and a philosopher?

EM: Earlier I explained that I can now move from any one of the three to any of the other two. There is an inter-connectedness of inspiration that can move in any direction among them. I now know that there are, and have been, hundreds of writers who paint and vice versa. The fact that I also do academic philosophy probably makes a difference, but I don’t know how widespread my particular kind of triad is. I have learnt that it is important to be aware that I do these different things, but I should not think of it as a division of myself. I am the same person when I paint, write or philosophize. Or when I swim or make coffee.

JB: Following these new paintings, what is next for Earl McKenzie?

EM: Before the end of 2015 I hope to publish The Flame of the Forest: A Memoir of Church Teachers’ College; my third collection of stories, Ernest Palmer’s Dream and Other Stories; and my first novel The Rooms of His Life. Since completing these I have been hard at work writing more short stories—a pet genre. I am also planning a philosophy textbook for students in the Caribbean. Poetry has a way of always being there. And to paraphrase Omar: The moving brush paints, and having painted, hopes to move on.