My mother, Vera Frankel, got out of Germany in 1939, just before getting out became much harder. In comfortable circumstances she and her family crossed the Atlantic on the Orinoco, bound for Mexico, where she was to spend nine years before she eventually made her way to San Franzisko (we never lived in the regular American city of “San Francisco”). Until the mid ’60s Mami was still a Mexican citizen. “I am proud to be a Mexican,” she would declare, and my father would ridicule her.

With just a few keystrokes at my computer, I’m able to see before me what the Orinoco looked like. It was not a white, white cruise ship loaded with seventeen flights of balconied staterooms, indoor and outdoor pools, casinos, bars, and bingo lounges; rather, Mami’s ship was just a stately ocean liner of the old kind belonging to the Hamburg Amerika Line, with a low black hull punctured by many portholes, a promenade deck, Spartan cabins, and two simple old-time smokestacks. I always picture her as happy on that crossing from old world to new. She made fun of people who got seasick. She looked after her somber, fussy old parents whom she adored and protected as they embarked on a new life in their fifties. My Mami was a child of nineteen.

When I look at pictures of the Orinoco, their black-and-whiteness reminds me of an embarrassing gap in my abilities to see. I am unable to imagine big chunks of the past in anything but black and white. There were no colors during the Civil War, the Roaring Twenties, the Depression. But earlier periods—before photography, when there was just painting—I have no trouble seeing them in bright, garish colors: the Revolutionary War, the court of Louis XIV, the travels of Marco Polo. Henry and Vera Frankel, in the forty years before I was born, could not have lived in a world in which true red, green, blue, and yellow were possible. Color began (or was reborn) about the time I was born. Or at least that’s what a silly voice inside me keeps telling me. When I recently saw a colorized photograph of Mark Twain posing in his garden, Abe Lincoln standing stiffly in his stovepipe hat, and people hanging around a filling station circa 1924, I was as stunned as a blind man who’d suddenly been given the gift of sight. For a moment I could almost believe Lincoln lived in a world of color. But only for a moment. I soon saw through the artifice of colorization, and Lincoln et al. receded into their film noir twilight.

Black and white: I can’t imagine the life of Vera Frankel, before my birth, with color. But maybe her life never had any colors at all. Before I came into it or after.

She never laughed. She was a short woman who smoked incessantly. I don’t think she ever fully adjusted to the U.S.A. I never received warmth from her in a physical way, and yet she was the human being I most longed to please. For her I stayed away from rough play with other boys. For her I listened only to decent classical music. For her I spoke with a German accent (it grew thicker around my parents at home, loosened up just a bit at school). I couldn’t say the word “back” like an American; I said “beck.” The “a” in the American pronunciation of “back” was daring, forbidden, erotic. If I was rough and masculine like the other boys, she would be hurt and angry. It was safer and easier to play with dolls.

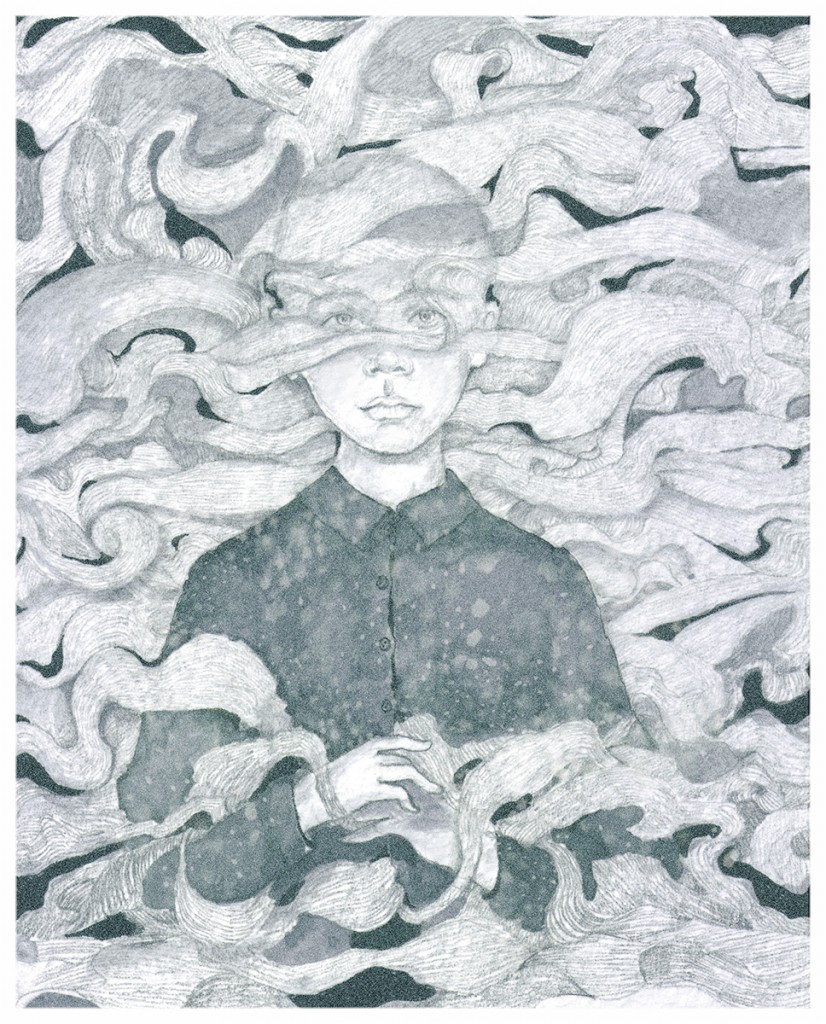

When my hair got tousled or grew too long, my Mami would point at me and cry “Struwwelpeter!” invoking the German storybook character who’s let his nails grow longer than his fingers and wears his hair in a kind of blond Afro style that dwarfs his little round head. In the story of the thumb-sucker, from the same book, a mother warns her five-year-old Konrad not to suck his thumb, but as soon as she leaves the house he sticks his thumb in his mouth. Then the Cutter bursts in with giant scissors and shears off not only the offending thumb but the other one as well. Hans Guck-in-die-Luft—Hans Look-in-the-Air—never watches where he’s going, ends up in a pond with three puzzled fish, and must be rescued by passing men. Hans survives, but the Suppen-Kaspar isn’t as lucky. He’s a rotund child who refuses to eat his soup. “Ich esse meine Suppe nicht! / Nein, meine Suppe eß ich nicht!” (“I will not eat my soup! / No, my soup I will not eat!”) Every day he throws a tantrum, until after four days he’s a ghastly stick figure: “Am vierten Tage endlich gar / der Kaspar wie ein Fädchen war. / Er wog vielleicht ein halbes Lot / und war am fünften Tage tot.” (It came to pass in four short days / half a shekel was all he weighed. / “He’s light as a feather,” his mother said. / One morning later she found him dead.) Vengeance. Violence. Cruelty. Mutilation. These seemed routine and normal occurrences to me, and when I hear modern German parents speak of the “harshness” of the storybook I grew up with (my first book), I’m always surprised. Whenever I didn’t watch my step, my mother would call, “Hans Guck-in-die-Luft!” When I sucked on my thumb, my mother would call, “Der Schneider kommt mit der Scher!” The Cutter, with his scissors, is coming for you.

One of Mami’s strictest notions had to do with shirt buttons. All buttons must always be done up. No open collars. The neck should feel tight. No visible neck to anyone! I went to school with a big brown briefcase and all buttons buttoned. About the second grade I noticed boys playing rough in the yard, with open collars, and sometimes when it got hot, they undid more than one button or peeled off their shirts altogether. I stared and wanted to be like them. It was unsettling to look at them.

My mother did not allow me to casually, spontaneously, walk home with another child. She insisted on days of planning, promises, negotiations, agreements with all parties involved. And other children were not granted access to our house unless they made an appointment well ahead of time. There wasn’t anything casual about Vera Frankel—or Henry Frankel. The windows were always kept tightly shut, except during a heat wave. The dogs were kept on a tight leash and locked up in the basement at night. And the smoke from her cigarettes filled the house (no one, in those days, knew about passive smoking). It was hard to breathe, with the smoke finding and settling in every corner of the house; it was hard with the closed windows, the heater on almost as high as it would go, and every single button of my shirt done up safe and tight, over my undershirts and under the red or blue cardigan sweaters she had me wear.

Once in a while, after much pleading and planning, I was granted permission to go home with Stephen, my friend. One afternoon, when we were not more than eight years old, the two of us walked to his house after school to work on our little project about the Children’s Crusade.

I lived on 36th Avenue with a view of Sunset Boulevard and parks, but Stephen’s family had a dingy house up on a hill. In that house his parents had managed to squeeze in six children along with a few cats and dogs. His father was a milkman. To this day, whenever I read fiction that takes place in a working-class house, I picture Stephen’s sad and happy little place, especially the kitchen, with its basic white table and its back door that opened to a rickety staircase and a yard consisting of sand and a lone bush.

Stephen shared a room with three brothers, all conveniently away that day. A desk by the window overlooked his sandbox yard; together we sat there and tried to work on our report.

We couldn’t focus on it for long. Soon we moved to the lower bunk bed. He asked me why I always wore my shirts buttoned up all the way, why I always stayed so closed up. He undid the top buttons for me. We took off our shoes and socks and lay back. So this was the way of wholesome, warm-blooded Americans: forbidden skin and hair and foot and armpit smells. Boy warmth. He kept telling me, “Relax, you gotta relax.” More and more buttons came undone as we pretended to be a dumb, temporary mom and dad. This was “playing house,” chaotic, silly, perfect. It was so good to be bad that we forgot all about the Children’s Crusade there on the pleasantly smelly lower bunk. I could breathe in this room, where the window was open and the tattered curtain billowed in the breeze. Stephen was pale with a perky, smart face (he was smart enough to be put in the “Enrichment Class” for gifted kids), he had dark bushy hair and thick lips and good eyebrows—and he consented to be my friend! What was there to talk about in that good room that smelled of used pillows, old blankets and socks? He pretended to be the dad, coming home from work “bushed” (his word), and I let him fall on me and pampered him, and wanted to go on pampering. In the middle of my body, in front, I felt an unusual tension and stiffness that wouldn’t go away, but I said nothing. We played, and I shed my German accent while we played: his handsome naturalness was rubbing off on me. It was good to be bad, but surely I would be punished for my thoughts and actions? I must not betray my well-meaning, strict, vulnerable parents by this contact with the wholesome world. Would I be punished for lying here so freely with my friend? Would God punish me again by making Mami and Deddi fight? I pronounced God the German way: Gott. Would Gott punish me for betraying my Mami and Deddi and trying to be cool and American like the other boys?

That night I folded my hands and, in a high-pitched voice, recited my nightly German poem-prayer in front of Mami and Deddi at bedtime:

Müde bin ich, geh’ zur Ruh’,

Schließe beide Äuglein zu;

Vater, laß die Augen dein

Über meinem Bettchen sein!

Amen

Tired am I, and go to rest,

Close both my little eyes.

Father in heaven, may your eyes

Watch over my little bed.

Amen

(A Gentile theme, invoking Jesus and blood, entered the poem after the first stanza. I only discovered this later in life. All those growing-up years, the prayer was just the four harmless lines that my parents had taught me.)

I slept.

Around midnight: the shattering of glass, the breaking open of sleep, the healthy, complete sleep of an eight-year-old. It was as if someone had thrown a grenade into my room and disfigured sleep for good. And I’d thought I was safe in that room, in my little bed under the map of the world. I ran into my parents’ bedroom next door and found all lights on, even the obtrusive ceiling light. Glass and blood all over my father’s side of the bed, near the door. Mami had thrown an ashtray at Deddi’s face and just missed blinding him. Impossible, that an ashtray colliding with a pair of eyeglasses could make as much noise as the smashing of a whole glass wall.

Sleep would not be a safe place ever again.

Blood. Glass shards littering the white sheets and gently pastel comforter. German cuss words of 1930. Deddi sitting stunned on the bed, in his pajamas, the skin on his nose torn open, his face indecent with blood.