Woodstock is in your mind

Not the present or the past

It can happen anywhere, anytime

Bring back the sixties, man.

(“Bring Back the Sixties, Man” from Rock and Roll Music from the Planet Earth,

Country Joe McDonald, 1978)

Washing the dishes at the Carnival Café was a deeply immersive experience. It didn’t occur to the collective to buy a machine; washing was done by hand in a traditional three-sink setup—scrape on the left, soap in the center, rinse on the right. Gloved hands were in and out of warm water repeatedly as the dishwasher, sunglasses on, headphones over the ears, grooved to the music from the Café’s lumbering Sony stereo reel-to-reel tape deck. Sink to sink to drying rack, all shift long, a rhythm broken only by occasional trips around the kitchen to put things away, headphones trailing a fifty-foot cord so the dishwasher’s private reverie could continue unabated—which was nice, when in the rest of life things had become somewhat appallingly communal.

But in 1969 communalism seemed like a very reasonable response to the hypocritical warmongering and planet-killing corruption of corporate capitalism. We, the youth of the world, were fighting a war for the human spirit. It was happening everywhere—Paris, London, Bonn, Mexico City. We all had to do our part. It was our duty, our right, and our mandate to wrest the world back from the stranglehold of a culture that practiced racism and sexism, oppressed the working class, raped the Third World to feed the mind-numbing consumerism of the exploitive West—and hated rock and roll.

“Counterculture” was an idea that lumped together disparate groups espousing a vast range of competing ideologies. My subgroup in this demography, the “freaks,” believed in a sort of radical probity, “voluntary simplicity,” rejecting conspicuous consumption for a small, peaceful future, impoverished but pure—absolute democracy, communitarian values, and personal freedom. In those mid-sixties to early-seventies years, young people lived in collective houses, planted community gardens, started food conspiracies and a range of businesses, building a holistic alternative intended to separate us from the mainstream economy. Think globally, act locally!

The Carnival Café was my front in the culture war.

One hot and lazy summer day in 1971, my girlfriend, Margaret, drove us up Colorado’s Boulder Canyon in her bright yellow VW Bug. A right onto unpaved Sugarloaf Mountain Road led to an even rougher dirt side road. We bounced up the rocky and rutted track to its end, parking next to a dusty, dark green 1956 Chevy pickup. Taking my hand, Margaret led me across a wide meadow on a path trod out of knee-high prairie grasses and into the trees. We emerged into a clearing at the point of a small ridge. A tepee stood there, commanding a view across a valley of mountain forests marching downhill toward Kansas.

I remember being amazed at how much like a tepee the tepee actually looked. Its poles rose high out of the open smoke flaps, their narrow points etched against the background of brown earth, green trees, blue sky, and white clouds. I was overcome by the sense of place—the tepee belonged there, in that spot, on that ridge, testimony to a life destroyed by the same forces we youth were resisting.

Back in reality, Margaret had her arm around a young woman dressed in denim overalls and green T-shirt.

“Mark,” she said. “This is Mady. She lives here.”

“Wow,” I said. “All the time?”

“Enough of it!” Mady laughed, a tingling, musical laugh I still can hear. I liked her immediately; she had a warm smile, thoughtful brown eyes, cascading brown hair, and an open, welcoming spirit. In many ways she would become the emotional heart of the collective. “Go on inside, if you want,” she said.

She and Margaret went down to the garden, where Mady’s childhood friend Donna was weeding. I lifted the tepee’s door cover and went inside. A pretty black-haired Jewish girl in a T-shirt and shorts was lying on Mady’s mattress, barefoot, looking out at the sky through the forest of crossed poles. “Hi,” she said. “I’m Anne.” She and Mady had been neighbors in their college dorm. Anne proceeded to tell me an amazing story about visiting her ex-boyfriend in a cult on a small island near Vancouver, from which, fearing for both her sanity and independence, she had fled at midnight. She and I became instant friends. Forty-six years later, I’m still married to her.

In the fall of 1971, a number of us enrolled in a mime class taught by one of the New Age transplants to Boulder, the Moroccan/French/Jewish master Samuel Avital. “We do the possible and only the possible!” Samuel would thunder, his slight body projecting attention, knuckles emphatically rapping on the table, his philosophy right in line with the times. One of the other students in that class was Rob; in the collective he became the calm counterbalance to my mania. Although mime didn’t last for most of us, it was in Samuel’s class that we began to recognize the possible: to form our tribe, to thread the quilt that became the Carnival Café.

Be the change! I reveled in my vision of a life of service to the people. The purer I was, the more my energy would help change the world. Yet my personal life was tumultuous. Margaret broke up with me, and devastated, I moved into a tepee and lived there through the winter. My tepee was sewn from green, water-resistant boat canvas, erected on a flat spot carved out of the forested hillside. The ground inside was covered with old carpet scrounged from flooring-company dumpsters. I had a salvaged mattress, and a few milk crates for storage. The tepee’s edges were weighted with rocks and dirt so the wind didn’t blow in under the skirt during storms, and the door and smoke flaps closed securely when it would rain or snow. I cooked and heated with a ten-dollar army surplus barrel stove, vented with a stovepipe to the outdoors, burning wood to cook and coal for heat overnight. Water came from an overflow valve in the pipe that fed Boulder’s purification plant.

I was alone, but not lonely. Over that winter of 1971-72, the group of friends grew to thirteen (plus Karen’s two-year-old son, Ethan), and things began to get complicated. Each of us had to navigate friendship, sex, commitment, and work against a backdrop of socialist values, feminism, environmental awareness, rage, politics, music, and dope. The personal is political. We were trying to create an emotional language to describe relationships about which we had not the slightest clue. What was private? What was public? What did one owe the group? What did anyone owe each other?

The women formed a consciousness-raising group, more deeply exploring their relationships with each other and challenging their relationships with the men. They developed that intense intimacy that women often do. We men worked at it, but layering such a moving target onto the normal anxieties of a young man engendered a deep emotional bewilderment. Simply wanting a woman was suspect, likely a vestige of patriarchy; the quiet ease of male companionship looked like emotional reticence (which, admittedly, it sometimes was). It was no surprise that relations between the genders often became frosty. A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle. Nevertheless, all of us, men and women alike, dove into our relationships with seriousness and glee. We challenged, we fought, we made up, we exposed ourselves to each other, we loved each other a lot of the time, and through it all, we became greater than the sum of our parts.

Winter turned into spring, 1972. The tepees were lovely in the warm weather. Rolling the cover five or six feet up the poles created a breezy pavilion with a view. We spent many Sundays sitting in one tepee or another, trying out ideas driven from the desire to build what I imagined would be a permanent alternate community. Buying property somewhere. Starting a theater group. But then it got real; the Family Table vegetarian restaurant came up for sale. And we acted, pooling our meager assets for working capital and borrowing the $6,000 purchase price from my parents. The café was ours.

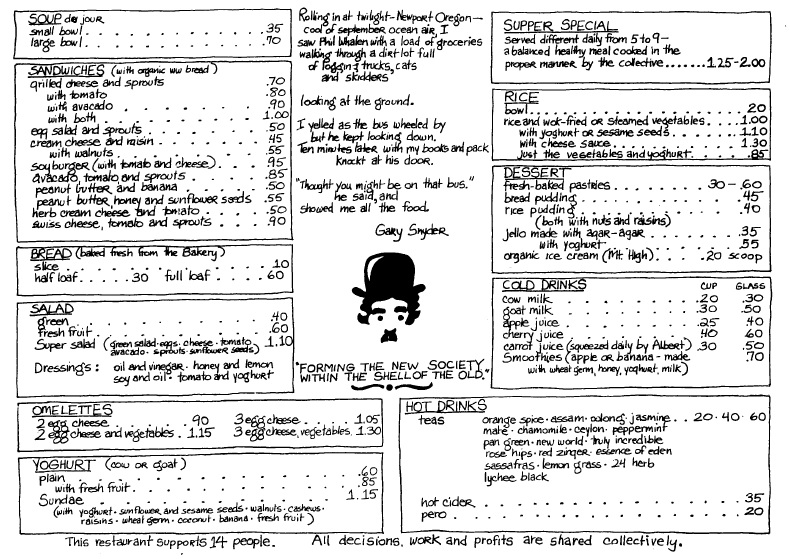

It sat in the center of a single-story row of old, beat-up storefronts, tiny businesses clinging to the edge of commerce in a block wearily awaiting the wrecker’s ball. Floor-to-ceiling windows fronted the street. The open kitchen was in the back. A long U-shaped counter with eight backless stools on each side dominated the dining area, with small tables arrayed down each wall that brought the capacity to thirty-six seats. The equipment was old, but still functional. The walk-in refrigerator, out the back door in the parking lot, was secured by a simple padlock and an abiding trust in the honesty of our fellow citizens. All the storefronts shared a single bathroom in the narrow back hall, made even narrower by the storage racks for the café’s dry goods. We gave the interior a fresh coat of paint and renamed it the Carnival Café. It was apt. We had met through theater, and the irony of naming a vegetarian restaurant “Carnival” was not lost on us either.

We Carnies didn’t see ourselves as being in the restaurant business. We were in the social-change business. We kept the place clean enough for the health department, safe enough for the fire department, compliant enough for the tax department, and solvent enough to pay its vendors and installments on the purchase loan. Five people worked on a shift and would choose their job in that shift; two servers, two cooks, and a dishwasher. The collective lived out of one checkbook with twelve signers (Anne, smartly, had opted out of the asset pool), “the Sojourner Truth Memorial Checking Account.” The Café paid the rent on the two houses we lived in, food was infinitely available from the storage room shelves, we each got a bit of cash in our pockets, and we had our community. For that brief, magical, perfect moment, we had done it. Be the change!

We were quite a show—a proud collective living, working, being together. Vegetarian, artistic, cooperative, colorful, flamboyant. Hairy. I often worked in a long skirt I made out of a pair of jeans with someone’s abandoned curtains as the mid-panel. And the regulars were our equal in every way. The dentist Martin Spector would shimmy in, knees bent just low enough so the four-year-old child standing on his shoulders could make it safely through the doorway without disturbing the two-year-old on his hip. I remember Wind carefully tucking his chest-length beard away from his soup; Ulee voluntarily spending hours, days, methodically scrubbing the caked-on grease from the back of our woks, polishing each to a mirrorlike shine; Damian’s diaphanous purple chiffon pants as incoherent as his world view; Wim, the 6-foot-4-inch NOAA sailplane pilot, who took girls and gurus gliding on the updrafts of the front range; Warren and Este’s welcome presence as they tucked their instruments under a table to eat before playing for their supper. We were the hippie crossroads of Boulder, hosting locals and travelers alike, feeding poor, stoned-out, wandering kids out of the leftovers.

We lived our mission. Our bible wasn’t Joy of Cooking, it was Diet for a Small Planet. We made all the soup stocks and sauces. We baked the desserts, and the breakfast muffins and scones. Albert, an aging refugee of the “right living” movement of the thirties delivered fresh carrot juice daily. Mo Siegel, then founding Celestial Seasonings, delivered tea to us on his bicycle, out of a backpack. We did not serve coffee, which precipitated vitriolic debate when we began to open for breakfast. What were we about? Serving the people what they want, or modeling a norm of healthy eating? Those of us who were unhealthy enough to be coffee drinkers would hypocritically make our own pot in the kitchen.

We bought the restaurant because we wanted to do something together, but not surprisingly, motivation rapidly crumbled in the face of the realities of restaurant work. I was a total idealist, but narcissistic. I regarded the restaurant as a political statement, found my own behaviors irreproachable, and expected my partners to operate with my values. Imagine my dismay when that turned out not to be the case!

The scene—Sunday morning meeting:

Mark: “So you can’t just take food out of the walk-in willy-nilly. It belongs to the restaurant.”

Rob: “Why not? Isn’t it my food? Isn’t it my pay?”

Mark: “Yes, but if you take too much of one thing, then we won’t be able to feed the customers.”

Rob: “We get deliveries every day.”

Mark: “But we don’t get everything delivered every day. We need to sell enough of them to be able to pay for them.”

Donna: “So I put everything I had into this place, and now you are telling me I can’t eat here?”

Mark: “No! I’m just asking you to be conscious of what’s there and what it costs.”

Rob: “This is ridiculous.” He opens the register and takes out forty bucks.

Rob (in his best Brooklyn accent): “C’mon, I’m taking all youse guys out. It’s on me.”

Several people leave.

Mark: “What just happened?”

Margaret: “It was a classic failure to communicate.”

Mark: “But someone’s gotta do it.”

Margaret: “Who elected you?”

She had a point. Nevertheless, for a short span of time we believed deeply in our world of sharing, cooperation, and trust. And we loved each other with a pure yet childish love, a love laden with unconscious expectations, yielding both deep satisfactions and bitter disappointments. This helped crystallize change, one by one setting each of us on the road to adulthood. The urge to intimacy that brought us together became an urge for independence driving us apart. The collective became a field of play against which each member’s biases, neuroses, and other predilections were played out.

Karen: “Mark, you really should wear a hairnet.”

Mark: “My hair is OK. It’s in pigtails.”

Karen: “It still could end up in the food. And if the health inspector sees you, we could get fined.”

Mark: “It won’t. But I can wear a bandanna.” He puts on his bandanna.

Karen: “When was the last time you washed that thing?”

The collective lasted for six months. We figured out an amicable divorce. But we also did what without a doubt was the single most radical thing we could have done: we gave the restaurant away. In the spring of 1973 the Carnival Café was restructured into a community-based cooperative, run by those who showed up at the Sunday morning meeting, “owned” by those who put their names on the annual business-license renewal application. These ensuing “owners” paid off the loan, and the Café survived until the building was torn down in 1978.

I left Boulder in January of 1974. Still a true believer, I worked for years in a traditional consumer cooperative, only to be disappointed one final time. White, middle-class, and Jewish, with a strong family, I was able to reenter the mainstream. I went back to school. Anne and I married, bought a house, had kids, and built careers. Yet the heart of the sixties still beats in my breast. These days, I take what social impact I can get and am thankful. Stay hungry, stay foolish.

I wish we could have done more: today’s youth face challenges that remain depressingly the same. Unnecessary wars in far-off places. Forty more years of carbon in the air. Inequality even more baked into the system. But we Carnies, deep into our sixties, have an even greater stake now: these youth are our children.

The capacity of youth is always underestimated, and as in all generations, their hope in the face of adult despair is our greatest legacy. These fantastic kids face huge challenges as world stewardship comes crashing down the timeline toward them, yet the Internet gives them tools for connection that reach far beyond collectivism. I can only hope that in all of this current tumult—economic, social, political—a deeper change is continuing to grow.

Let a thousand flowers bloom.