It smells like meat. Raw. Outside, the sheep talk to each other in the rain. They bleat and mew, strong and steady. I wonder if they say, “Why are we in this pen? Why are we in this pen? We want to go back to our pasture.”

Inside, they are dead, and for sale. Chops. Sausage. Also for sale, water buffalo. Ground, steak, roast. Water buffalo? In a rural Oregon butcher shop, this is not what I expect. This shop is the nearest business to my house. Five miles from my farm, up a windy hillside and down a narrow lane and up a country highway. Trees, trees, trees, so green is the drive to Belva’s Meat Market. Moss on everything but the pavement and the animals. Moss on a broke down truck abandoned on an overgrown, foreclosed upon nursery across the street from Belva’s. Constant green, growth, growing.

The woman behind the counter here, the most amazingly beautiful woman I have seen in my life, has just ripped me off. She wrapped my order and took my credit card for payment. Upon overcharging me, she declared that she did not know how to refund my money, and I would have to pick more meat. I had been warned she would do this and to bring cash, but I forgot the cash, because I was excited to gaze at Ivan. Harmless gazing: I am married, but how could I not be excited to gaze at Ivan? Upon my entering the shop, the woman behind the counter caught me gazing at Ivan, giggling a bit as I said hello to him, and he then introduced her as his wife. I wonder if the overcharge was her power play. Her accent is deep as Russian snow and I cannot detect the truth inside it. She hands my extra meat and stares, so beautiful, but dead on, surely as the devil must stare before he rapes you of your soul for a handful of coins.

This is my first time at Belva’s Meat Market. I am new to town. As I leave with my four extra pounds of sausage and water buffalo, I see the Russians also sell wine. I take note. It is expensive, but wine is wine when wine is such a distant commodity. Fifteen minutes by car to the nearest town to my house; Belva’s is only seven minutes away. I consider the convenience, but somehow, though excited and a borderline alcoholic, I know I will never come back to Belva’s.

I met the owner of Belva’s last week. Ivan came to speak to my husband about lettuce, and to invite us to be patrons of his meat market. We grow lettuce. Ivan is a butcher. He let us know he would slaughter and butcher our livestock for us. We told him we had none yet, with no immediate plans to procure any.

He looked blank and still. “But you have barns and pasture and sixty acres. I do not understand this lack of animals.”

We explained it as a financial investment we are unready to make.

He scratched his head. “This is stupid. You need some meat.”

Ivan is six feet five inches tall and from Bogorodsk, in the Moscow Oblast. He came to Oregon six years ago, at age twenty. I wanted to listen to what he was saying. His delivery was compelling.

He is handsome as hell. Blond, stormy. Muscles and grit. Narrow, bright eyes. Ivan. Sigh. He looks mean, but honest. Earnest. Curious.

He is blunt as a dull knife, too. He looked around our farm, a recent purchase. In need of repair; gone to seed. We have fifteen buildings, sixty acres, two rivers and a flock of transplanted urban chickens. We have never farmed before, garden hobbyists who came into a windfall and decided to invest it on a dilapidated former flower plantation. We have one greenhouse up and running, a bounty of greens and deformed carrots, all organic, all kind of ugly, some moldy. The greenhouse is 1930s vintage, part leaded glass, part missing glass and part plastic sheeting, rigged to let the sun in and keep the cold and wind out.

“You need to fix this glass, Steven. That sheeting looks like shit,” Ivan said to my husband. Ivan is sedate and intense at the same time, like when a parent whispers their anger instead of yelling it. Then, the child really listens. Steven looked at the greenhouse, half laughing and half, I imagined, wanting to do as Ivan said.

Ivan turned to me. Some might say he turned on me. “What are you?”

“What am I?” I had an existential crisis. What am I, I thought? What am I? Why was this handsome man asking me to self-actualize?

“Yes. What are you? You are dark.” His accent is so thick that for a moment, I did not understand the word dark. I stood, dumb and starry-eyed. Ivan. “Where are your people from, Elizabeth? We are not used to dark people in Boring.”

He rolled the letter z in Elizabeth into something like a letter r. I stood silent, thinking zephyr, or Zorro. Steven spoke for me.

“Elizabeth is Dominican and Greek, Ivan.”

Ivan laughed. “I do not want to be here when she gets pissed at you. There will be more broken glass.” Steven laughed, too, but I giggled. Steven looked at me sideways. I snapped out of it.

“Really, though, Steven. I have to ask you. Why did you buy this shit hole? You like this? You like these falling down buildings and this mud? This place is shit. I left Russia to get away from this kind of shit. You need to fix this shit up. Does your wife like this shit? Maybe it is better than Greece or Dominica, but she should have stayed home where it is at least warm and sunny, if this is true.”

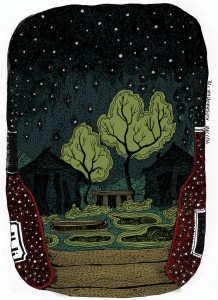

We fell silent. Ivan left shortly after, and we drank two bedtime bottles of wine in our falling down shit hole, looking out at the stars, knowing there was very little between us and their light but decades of wear and some windowpanes.