I. THE BOOK

The sociocultural significance of Donald Duck vs. Daffy Duck

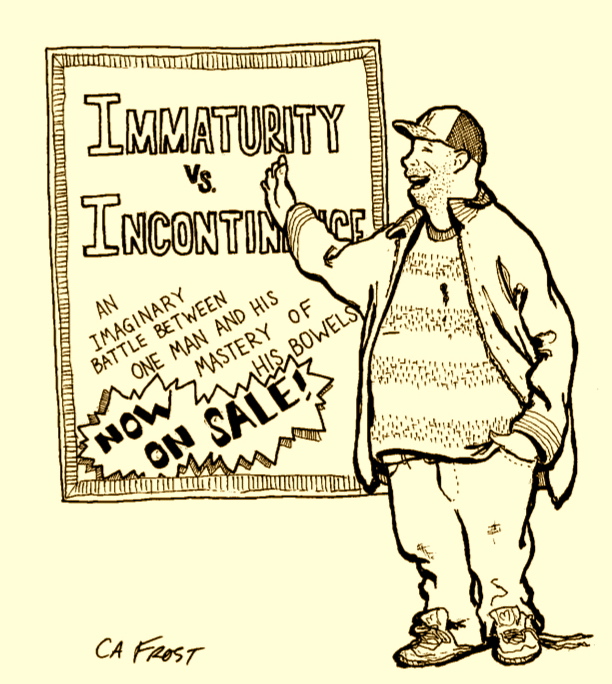

Last year, I published my first book: Santa vs. Satan: The Official Compendium of Imaginary Fights. Why imaginary fights? Because they matter. “Who would win between . . ?” has been a fundamental question discussed among men through the ages. Sadly, adult responsibilities like “earning a living” and “having a girlfriend” have conspired to make it impossible for men to devote to this issue the scholarship it so deeply deserves.

Take for example, the question of Daffy vs. Donald-and, by extension, Disney vs. Looney Tunes. This is as clear a dividing line for the preadolescent boy as Marvel vs. DC...Spiderman vs. Superman...American vs. National League...the kids allowed to eat junk food vs. the kids who aren’t. In short, these things define who we are, and how we see the world. Kids who liked Disney cartoons gave hugs for no reason, and believed everything would work out fine. Looney Tunes kids might hit you just for standing there, and were waiting for something else to go wrong.

Nothing truly awful ever happens in a Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck cartoon. The protagonists are adorable, and unlike either humans or their animal counterparts, Donald Duck isn’t much like a person or a duck, but rather an idealized amalgamation, designed to make the young, impressionable, and innocent believe in a better, kinder, more awww-inducing world-a smoothed-out utopia complete with hundred-dollar day passes, family packages, and must-have souvenirs. Sure, unlike Mickey, Donald gets angry, shouts, and stomps a lot. But his fury seems random, undirected, like an adorable baby crying to be heard.

On the other hand, characters in Looney Tunes cartoons have every reason to be upset. Anything that can go badly in a Looney Tunes cartoon generally does, often in a spectacularly violent manner. These cartoons tell children a boulder will fall on your head. A bomb will go off in your face. You will step on a rake, over and over and over again. Unlike in the Disney universe, heightened unreality exists not to mask the cruel underlying truth, but to maximize its impact: you defy gravity just long enough to know you’re about to fall, and wave goodbye. And the characters are us, in all our ugly pettiness, duplicity, jealousy, and frustration.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Daffy, who is Salieri to Bugs’ Amadeus, Garfunkel to his Simon, Chasez to his Timberlake. Daffy’s world is cruel and unjust, and he is wholly incapable of rising above it. He’s for the kids whose parents yell too much, who get carob instead of chocolate, who know exactly which table is the cool table, and that they won’t get to sit at it. God bless Daffy for that.

From Santa vs. Satan: An Official Compendium Of Imaginary Fights, published by Three Rivers Press.

II. WHAT THE BOOK DID TO ME

Stage I. Overconfidence

I am a big, slothlike, and a Jew. My book is medium-sized, sprightly, and agnostic. Both of us have slept with people you love.

I am a big, slothlike, and a Jew. My book is medium-sized, sprightly, and agnostic. Both of us have slept with people you love.

Shortly after submitting my final manuscript, I was asked by my publisher to remove a Rachael Ray reference, because it turns out Rachael Ray and I have the same publisher. Rachel Ray, however, makes our publisher 3 million dollars a year. To be fair to the publisher, my Rachael Ray reference was not complimentary. I said she was an animal that eats feces. More specifically, I put her last on a 10-item list of “Animals That Eat Feces,” after the panda and the naked mole rat. (Which shows you that, adorably cute or hideously ugly, the animal kingdom is full of shit-eaters.)

My editor promptly e-mailed me, saying “Come on! You can’t say she eats her own feces!” I wanted to point out that I didn’t say she eats her own feces. But the fact that Rachael Ray eats feces is undeniable. Have you seen any of her shows?

At any rate, I fought and fought for the right to call Rachael Ray a shit-eater, which is much like Mandela fighting for a free South Africa. Except unlike Mandela, I lost. Now I vow to do whatever is in my power to make this book successful enough for me to completely slander someone I’ve never met in my next book.

Stage 2. Deflation, Defeat

I did not check my account balance this month and yesterday discovered to my wonderment that I am dead broke with debts to pay. It’s a special kind of 32-year-old who pays no mind to his finances, and doesn’t have the foresight that without income, funds tend to deteriorate. But this is the yin to my yang, so to speak, as I would not have written a book about imaginary fights in the first place were I the sort of adult who could hold down a regular job or keep track of his money.

This week, my mother took me out for lunch, and to see my book (and its poster) in the window of the Barnes and Noble on 46th Street and 5th Avenue. This would have been a proud moment for mother and son, but I was sulky, having already had to ask my mom to borrow money. (Headline: “HUMOR WRITER RETURNS TO WOMB; NEVER SEEN AGAIN.”)

My mom did agree to lend me some dough, but not before I received a harsh but fair speech complete with reminder that she’s not rolling in cash either, and would be doing better if I hadn’t given her a stock tip that made its way through the bowels of the market and straight into the toilet with a terrible plop.

The subject of finances was interrupted by Mother making Son pose in front of his book, jamming up midtown pedestrian traffic as she determinedly tried to figure out how to work a digital camera and I tried halfheartedly to turn my frown upside down. It’s possible that I barked “Take the damn picture already!” But I’m not willing to take full responsibility for my actions. (See above.)

Stage 3. Acceptance: A fellow fighter

There’s an oddball man in my neighborhood who wanders the block all day, looking for people to shake his hand and talk to him. When I first met him a few years ago he had three teeth. Now, he’s down to half a tooth; just the faintest reminder of what a toothed life was like. These days, he repeats a single question to anyone who will talk to him, which seems to be a population comprised of Me. The question is: “You know Michelle?” After he asks me this two or three times and I say no each time, he turns away from me and starts barking something like “Hey yo, dit-dit-dit-oh-oh!”

I don’t like this question, for two reasons:

1) I don’t know Michelle, and he’d know that if he’d just listen to me.

2) He used to have a much better question.

I first met this man by accident. I was standing on the street looking down, when I heard “Hey yo,” and saw a big hand reaching out to me. I was shaking the hand before I realized that it was attached to a stranger. I generally avoid physical contact with strangers, particularly odd ones, but something about the way he sounded, how he just reached out, seemed nonthreatening. I still shake his hand every time it’s proffered; it just seems like the human thing to do.

The first time I shook his hand was also the first time he asked me what is now my favorite question in the world: “You goin’ get him?”

Am I going to get him? Golly, I don’t know. Who is he? Is he big? Is he mad? What did he do? Does he have friends? Weapons?

When You Goin’ Get Him (because, from that moment forward, this became his name) first asked me if I was, indeed, going to get him, I said “No.” That seemed to really disappoint You Goin’ Get Him. So the next few times I said: “I don’t know,” which was the most honest response, yet unfulfilling for us both.

But the fifth time I saw YGGH, things went down like this:

You Goin’ Get Him (shaking my hand): You goin’ get him?

Me: Yeah.

You Goin’ Get Him (taken aback): You goin’ get him?!

Me: Yeah. Yeah, I’m gonna get him.

You Goin’ Get Him: You goin’ mess him up?

Me: Yeah.

You Goin’ Get Him: You goin get him! Oh-oh-A-wooooh!

He, at that moment, was one happy, toothless oddball. I hadn’t given him an empty promise, either: I am going to get him. After all, YGGH and I know the beauty of imaginary fights: anything can happen.